The Last Movie Stars: Ethan Hawke pays a complex tribute to his idols

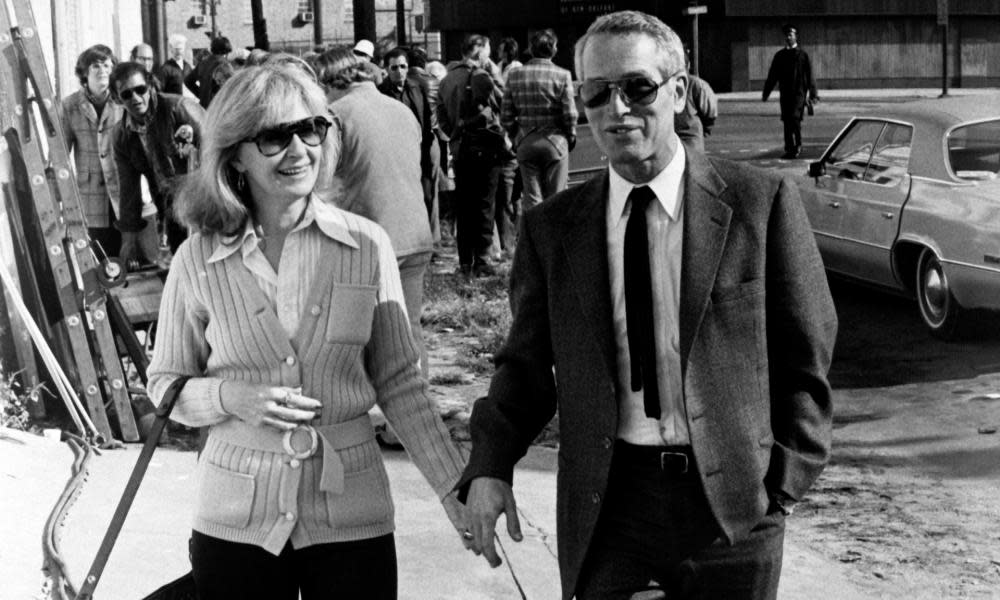

The Last Movie Stars, a new documentary series on Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward released to HBO Max this past weekend, occasionally allows its focus to drift to a third subject. Ethan Hawke presides as director and producer on the six episodes, and he makes no effort to minimize his own presence under some pretense of fly-on-the-wall objectivity. As much as his extensive research project exists to chronicle the lives and works of a Hollywood power couple in a league of their own, he also digests the narrative at hand by examining his own relationship to it.

Related: ‘Two out of five stories should be hot’: why pre-code cinema was a golden age for women

With a cavalcade of famous pals Zoom-ing in during the shaggy-haired early days of quarantine, a murderers’ row of actors’ actors who also record voiceover readings of archival documents, Hawke pontificates on how a generation of serious thespians modeled themselves and their careers after Newman and Woodward. For a substantive performer looking to cultivate a rich inner life of varied hobbies and intellectual pursuits to go along with A-list icon status, there’s no clearer exemplar than Newman, whose ice-blue eyes hid the soul of a Lee Strasberg student and racecar driver.

Considered as a whole, this tribute to the pair ’00s tabloid media would’ve dubbed Jaul (Poanne?) doubles as a case study in fandom practiced properly. The profile of the typical fan has been significantly warped over the past internet-besotted decade, now more closely associated with lockstep devotees of pop music or superhero movies, hordes prone to cyber-swarming anyone who challenges their absolute allegiance. Hawke trades this unquestioning fealty for an appreciation with a more critical bent, willing to acknowledge Newman’s sizable flaws alongside his virtues. For all his open admiration, Hawke constructs an even-keeled assessment of an essential artist and troubled man. In doing so, he demonstrates how to account for the problematic aspects of a personal favorite, a challenge for all of us that grows more pressing with every breaking scandal.

While he’s sculpted a public image of an alt-heartthrob farther from the movie-star mainstream than Newman, Hawke has still followed in the elder actor’s path: from-the-ground-up training in theater, consistently range-expanding screen roles under a host of esteemed auteurs, side endeavors too dedicated to be written off as dabbling. As the episodes touch on each canonical Newman performance, Hawke shares a beat of breathless awe with whoever he’s got on the line. “Denzel in Malcolm X. De Niro, Raging Bull. Paul Newman, Cool Hand Luke!” Hawke effuses, delivering some variation on this for Hud, The Sting, The Color of Money, and the rest. But his is a purposeful admiration, his compliments always couched in a thoughtful analysis of the characters Newman played and how they corresponded to his life story.

Though Hawke doesn’t talk around his identification with Newman, he does devote just as much time and attention to Woodward, and the shifting dynamic between the longtime spouses. It’s here that Hawke’s circumspect view of a larger-than-life legend really comes into play, as firsthand sources establish her to be a nobly suffering support beam to a husband on the verge of collapse. The series doesn’t gloss over Newman’s functional alcoholism, showing us home movies in which he sloppily toddles around his living room clutching a bottle. More unsettling still is a clip in which we see one of his children doing a convincing cross-eyed impression of Daddy under the influence, a sign of the negligent parenting for which he’d feel immense guilt later in life. (The death by overdose of his son, fledgling stuntman Scott, is Newman’s rock bottom.) George Clooney reads as Newman throughout the series, and infuses real anger into a rant that sees him defending his choices as a father by claiming that at least he didn’t beat his kids.

But life is long, and Newman’s thread continues. The latter episodes chart his redemption as he scales back his intake of alcohol – “just beer,” he maybe-jokes – and makes good through charity and outreach to those struggling with addiction. Hawke takes this without judgement, as he does the rest of Newman’s complicated journey. “The people I admire the most are the ones who overcome their demons and work with them, and that’s what I take from it,” Hawke told Business Insider last week. “If you don’t have shadow, you don’t have light.” He wisely eschews outright hero-worship for Newman’s greatness or dismissal for his darkness, instead assuming a nuanced view that accounts for all the frailty of human nature. Anyone invested in the arts must confront this contradiction constantly, that the people responsible for work we find beautiful or moving could nonetheless behave in ugly or cruel ways behind closed doors. The adult mind can hold two opposing thoughts at the same time, and in Hawke’s case, even fuse them into a wider comprehension of how a genius’ demons can inform and even motivate their finest hours. There’s no interest in condemnation nor exoneration here, a verdict either way being a useless roadblock to understanding. Newman has passed, his legacy cemented. He simply is, and Hawke accepts him on those self-evident terms.

The Last Movie Stars is now available on HBO Max in the US with a UK date to be announced

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies