The Last Temptation of Christ at 30: how Scorsese's drama still soars

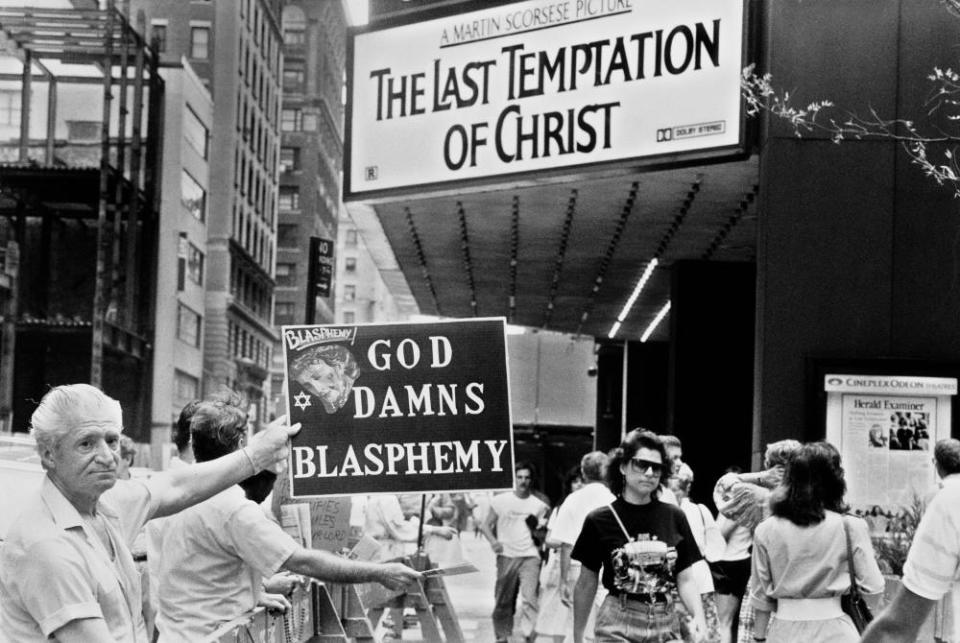

A few decades before Hollywood started reaping every last bit of arable intellectual property, Martin Scorsese imagined a gritty reboot of Jesus Christ. In the devout Christian’s retelling of the greatest story ever told – adapted, per a title card, from Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel and not the New Testament – star Willem Dafoe dared to play the son of God as a mortal, and a flawed one at that. His feathery-haired Jesus had a temper and an ego, defects of virtue that the holier texts would never allow. He speaks in a combination of scriptures and modern vernacular, an odd combination more pronounced in Harvey Keitel’s curly-headed Bronx Judas. Most scandalizing of all, Jesus has a bit of a libido to him, making graphic onscreen love to his wife Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey). At the time, religious groups were up in arms over what they saw as a blithely sacrilegious depiction of the Christ, and Blockbuster Video refused to stock the film.

Thirty years later, and the tongue-cluckers have largely won the battle. In the compact realm of explicitly religious cinema, the behemoth known as Pure Flix has flooded the market with morally clear-cut pabulum guaranteed to offend nobody except movie lovers. The likes of The Case for Christ, I’m Not Ashamed and the God’s Not Dead franchise move with a sense of black and white assuredness, dealing in Manichean absolutes from which the good is simply chosen over the evil. They also hold dominion over the box office, while the exceptions to the trend – the recent First Reformed and Scorsese’s 2016 drama Silence – languish in obscurity when not actively losing money. Those disciple films sacrificed a broader audience by eschewing the comforting clarity of organized religion for doubt, challenging their characters’ faith rather than blindly affirming it. They followed the primary teaching of Scorsese’s Jesus: he who claims to know the mind of God is farthest from it.

Uncertainty runs rampant through the nearly three-hour sprawl of Christ’s life and times, in turns tormenting and compelling him. Paul Schrader’s script introduces a sinewy Dafoe lugging crucifixes around in his work as a carpenter, effectively collaborating with the Romans in their persecution of the Jews. The radicalized Judas sways his intellectual peer to the cause of the Israelites’ liberation, and even then Jesus falters in his mission. As he sets out on the path of his destiny, he remains committed to his principles of love, compassion and forgiveness above the politicized stance forced upon him. Jesus gets the sense that both sides of this conflict want to make a pawn of him, and he’s torn between wanting to remain unaffiliated in the affairs of men and the clear moral imperative to put an end to persecution.

Of course Jesus eventually sides with the rebels, but that doesn’t provide him with any respite from his insecurities and misgivings. He’s eternally at war with himself, his every impulse challenged in his own mind. He’s filled with lust for Mary, and distrustful of the very pleasures of the flesh that he craves. As he screams atop the crucifix, he wants to be a good son and fulfill his purpose on the mortal plane; still, he’s confused and frustrated at the set of seemingly arbitrary, incredible steep demands that have been made of him by a God he cannot see.

In the most famed departure from the traditional scripture, Jesus allows himself to be fooled by Satan in the guise of his little girl guardian angel, climbing down off the cross and building a happy domesticity for himself with a wife and child. When he realizes he’s been fooled, the entire story resets itself and snaps back to the moment he made that choice. Crucially, he gets the opportunity to make good – transgression, penance, redemption.

That’s the three-part cycle that’s guided much of Scorsese’s work, from Taxi Driver to Silence. He has always treated religion as a philosophical expedition rather than a set of rigid guidelines, and he instills that searching impulse in his daringly imperfect protagonist. He depicts Jesus as something closer to a Christian than Christ, a man constantly parsing and re-interpreting his relationship to God depending on the given situation.

The Last Temptation of Christ is a film of questions and not of answers, Scorsese’s confession that the closest any of us can get to godliness is not full understanding, only partially-comprehending goodness. There’s arrogance in claiming enlightenment on Earth, and true humility only in prostration; Scorsese communes with God by accepting that some aspects of worship are mysteries and then wondering about them anyway, catching a glimpse of His light in the process of inquisition. Scorsese and his Christ figure collapse in unison at the film’s conclusion (and after 163 minutes of suffering, the audience might be there as well), acquiescing to the will of God without grasping the big picture of the cosmos. Their reward for submitting to the unknowable? Blinding white light, pealing celestial bells and the heaven of the end credits.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies