We independently evaluate the products we review. When you buy via links on our site, we may receive compensation. Read more about how we vet products and deals.

How Tim Burton's live-action 'Dumbo' deals with the original cartoon's most racist moment

Tim Burton’s remake of the Walt Disney cartoon classic, Dumbo, is coming down the track towards theaters. And although early reviews and box office predictions have been mixed, we’ll say this about the movie: It’s not the Dumbo you’ve seen before. Where previous Mouse House animation-to-live action translations like 2017’s Beauty and the Beast and 2016’s The Jungle Book have mostly stuck to the script and storyboards of their predecessors, Burton’s film makes a number of significant alterations to the 1941 original. For example, the entire second hour of live-action Dumbo tells an entirely new story, with Dumbo and his circus family being purchased by Michael Keaton’s corporate tycoon who transports them to “Dreamland” — a dark-hearted theme park with more than a few parallels to Disneyland. Here are the five biggest differences we spotted between the 1941 and 2019 versions.

The crow scene

Part of the reason why Burton’s Dumbo takes such liberties with the 1941 version is due to the fact that the earlier film features a number of sequences that couldn’t be put onscreen today in their original form. Chief among them is the infamous crow scene, in which the titular big-eared pachyderm and his rodent pal, Timothy Q. Mouse, wake up in a tree after a drunken, pink-elephant filled night, and find themselves surrounded by a murder of jovial crows, who speak and sing in the style of an African-American choir.

In fact, members of the Hall Johnson Choir — a prominent black choral group at the time — provide the background vocals of the characters’ big number, “When I See an Elephant Fly.” But a white actor, Cliff Edwards (who also voiced Jiminy Cricket in Disney’s seminal adaptation of Pinocchio the previous year) is the voice of the main bird, whose name is Jim Crow: a knowing reference to the exclusionary laws that kept blacks and whites separate and unequal in the South until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Audiences in 1941 would have recognized the crows as belonging to the minstrel show tradition, with Edwards essentially contributing the animated equivalent of performing in blackface. Seen today, though, the overt racial stereotyping makes the film profoundly uncomfortable to watch. The existence of the crow sequence has long complicated Dumbo‘s legacy, even though Disney has declined to take the film out of circulation in the same way they’ve consigned 1946’s Song of the South to their permanent vault. On a February episode of the NPR podcast, Code Switch, host Gene Demby called out Dumbo in his survey of the history of blackface in popular culture: “I used to listen to that song [‘When I See an Elephant Fly’] all the time growing up. I’m retroactively mad at my mom for letting me listen to this.”

It goes without saying that the crows are nowhere to be found in the new Dumbo, and their narrative function is fulfilled by human characters instead. In the cartoon, the birds provide Dumbo with a so-called “magic feather” that he believes activates his ability to fly. (For the record, that also makes the crows one of the earliest examples of the notorious “Magical Negro” cliché.) In Burton’s movie, the curious young heroine, Milly Farrier (Nico Parker), furnishes him with a feather as part of a science experiment. The results prove the same: With the feather in his trunk, Dumbo is able to take to the skies, until he learns that he’s been capable of flight all along.

No animals allowed

Humans are seen but rarely heard in the original Dumbo, which unfolds in a circus populated by kangaroos, tigers and bears… oh my! These days, there’s little joy left for circuses that make extensive use of animal acts, largely due to our increased awareness of animal abuse and the fight for animal rights. That’s probably why Burton’s Medici Brothers Circus — owned and operated by the brother-less Max Medici (Danny DeVito) — employs more humans that animals. His line-up includes clowns, strongmen and horse riders… and one very pregnant elephant, Mrs. Jumbo. (Pregnancy is also not depicted in the animated version; babies enter the world via stork.) Medici’s hope is that a cute baby elephant will bring some business to his failing operation, but that dream is dashed when audiences take a gander at Jumbo Jr.’s oversized ears. The few animals that are in the movie — including a brief cameo by Timothy — don’t get the chance to speak, either. That means that Dumbo’s name isn’t bestowed upon him by cruel fellow elephants, but rather via a poorly assembled sign.

Don’t strike up the band

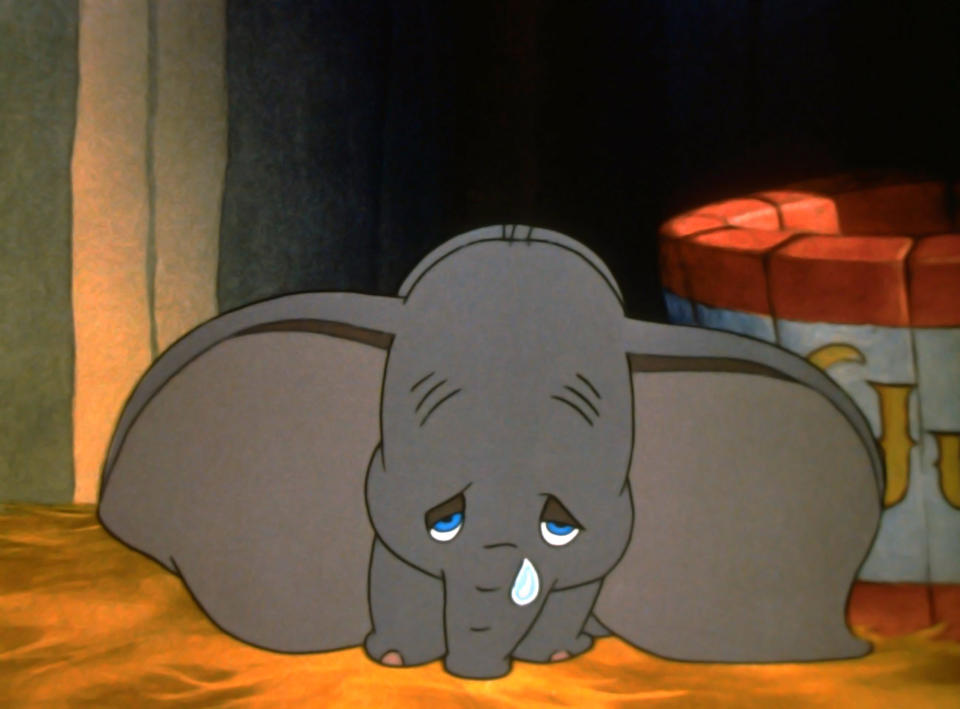

The 1941 Dumbo clocks in at a mere 64 minutes, and roughly half the film is sung rather than spoken. In between the opening number, “Look Out for Mr. Stork” and the closing reprise of “When I See an Elephant Fly,” audiences are treated to such vintage Disney tunes as “Casey Junior” and the movie’s most famous song, “Baby Mine,” which is crooned over the heartbreaking image of Dumbo being caressed by his imprisoned mother’s trunk. That moment is recreated in the 2019 film, with Sharon Rooney — who plays the circus’s mermaid act — singing “Baby Mine” in front of a campfire. (The version of “Baby Mine” included on the Dumbo soundtrack is performed by Arcade Fire.) Otherwise, though, none of the original songs are reprised in the new movie, although Burton’s regular composer, Danny Elfman, weaves in snippets from “Casey Junior” into the music that accompanies the opening sequence.

A happier, gentler circus

One of the tunes left off of the 2019 Dumbo‘s soundtrack is “The Song of the Roustabouts,” which accompanies a sequence in the original cartoon where the animals are forcibly enlisted to help the African-American crew raise the circus tent in the middle of a rainstorm. Boasting lyrics like “We work all day, we work all night, we never learned to read or write,” and “When other folks have gone to bed, we slave until we’re almost dead,” this sequence is plagued by the same racial insensitivities that make the crow scene impossible to recreate in a contemporary film. The images of the animals toiling in the mud and rain — often yoked to ropes and carrying heavy pieces of equipment — is similarly out of step with modern sensibilities. Thus, the Medici Circus doesn’t place the same demands on its animal or human population. Everyone pitches in to pitch the tent… and nobody has to work the late-night shift.

Pink elephants get bubbly

Generations of kids have learned about the perils of drinking after the animated Dumbo accidentally ingests champagne-spiked water and is treated to nightmarish visions of pink elephants parading about. Those creatures return in the new Dumbo, but not as alcohol-induced hallucinations. Instead, they’re part of the Dreamland circus, conjured for the crowd as giant soap bubbles whose contortions inspire cheers rather than chills.

Dumbo is playing in theaters now. Visit Fandango for ticket information. The original Dumbo can be rented or purchased on Amazon, iTunes and Vudu.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Disney goes dark: The Mouse House’s 8 scariest movie moments — and why they might be good for you

Why Tim Burton’s live-action ‘Dumbo’ is secretly an animal-rights movie

Want daily pop culture news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Entertainment & Lifestyle’s newsletter.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies