Victim at 60: the heartbreaking gay drama that pushed boundaries

Twenty seven minutes into Victim, after some circuitous beating around the bush, the word is dropped into the dialogue – an unprecedented bombshell on screen at the time, and if it no longer shocks today, you can still sense the film bracing for impact. It’s not a slur, or a profanity, but it was enough to make audiences wince and censors bristle: in 1961, the simple word “homosexual” was more dangerous than an idle swear. Its blunt appearance in Victim ensured the British film initially fell foul of US censors. The British Board of Film Censors let it squeak by with an X rating, though objected to a different scrap of innocuous dialogue, when one man says of another, “I wanted him.” Sixty years ago, the love that dared not speak its name began – as discreetly and politely as possible while maintaining some level of candour – to mutter it.

Related: Body Heat at 40: the sexiest and sweatiest film of the 80s

That Victim was made and seen at all in a climate of such wrong-headed moral panic is remarkable. That Basil Dearden’s film stands six decades later as a vital queer text, for all its compromises and socially baked-in offences, is a miracle, albeit one that demands some perspective and forgiveness from the contemporary viewer. A few years ago, Victim was rereleased in British cinemas; a young gay colleague of mine saw it and was aghast. “It’s just so homophobic,” he said with a shudder. Dearden and his collaborators would have been horrified by the accusation, having in 1961 made a film that was a new benchmark in its acceptance and understanding of gay characters. But my colleague wasn’t entirely wrong, either: Victim is perhaps most moving as a snapshot of how far the mid-century gay man had (or hadn’t) come in accepting himself, amid a surfeit of laws and popular discourse that cast him, with varying degrees of compassion, as an aberration of nature.

“If the law punished every abnormality, we’d be kept very busy,” says a police detective early in proceedings to his aggressively bigoted co-worker, after the latter has wondered aloud why “they” can’t simply lead normal lives to begin with. As expressions of allyship go, it’s on the tepid side – homosexuality is framed throughout Victim as an abnormality, a setback, an unfortunate condition to be managed, though as long as it was still illegal (for another six years) under the Sexual Offences Act, the filmmakers would have been hard pressed to present it any other way in a mainstream entertainment. “Nature played me a dirty trick,” complains one gay secondary character in the film; Victim dares to express sympathy for this point of view, though keeps its disagreement tacit.

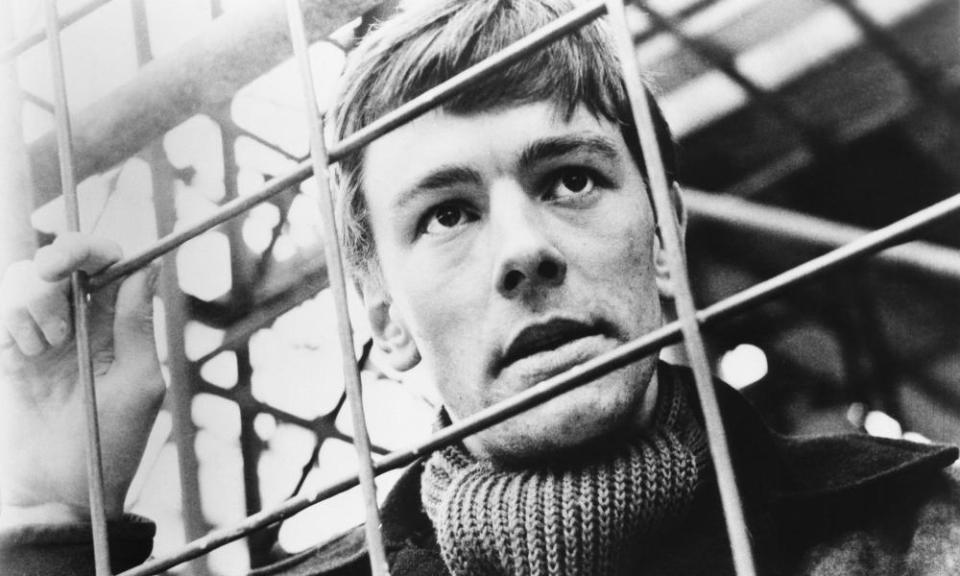

It’s certainly as chaste a boundary-breaking film about indecency as has ever been made: the “sex” bracketed in the troublesome word “homosexuality” is as far as it gets in acknowledging physical intercourse between men. Dirk Bogarde’s protagonist Melville Farr, a high-climbing London barrister, is presented as a gay man who has never acted on his forbidden desires. Whether he’s ever even had sex with Laura (Sylvia Syms), his patient, sweetly delusional beard of a wife, with whom he has no children, is a detail left for us to ponder. When he’s rumbled in a blackmail plot targeting an assortment of closeted gay men across the capital (beginning, fatally, with Boy Barrett, played by Peter McEnery, the young object of Farr’s affection) the smoking gun isn’t especially salacious: the blackmailers are in possession of a candid snap of a fully clothed Farr consoling a crying, fully clothed Barrett.

The photograph is tender, not explicit; as one lawyer points out, if the younger man wasn’t weeping, there’d be nothing incriminating about it at all, which tells you everything about the climate of macho paranoia in which the film was made. The film-makers, for their part, treat the shot coyly, like a volatile MacGuffin: that we never get a clear view of it all seems a timid dodge at first. Yet this skittish perspective ultimately gestures at the real taboo tackled in its story: it’s not the “unnatural” fact of men having sex that most offends the villains here, but the possibility of sustained emotional intimacy between them – a more difficult force to police.

“Why should I live outside the law because I found love the only way I can?” asks another of the blackmailers’ victims, pre-empting today’s now-ubiquitous “love is love” sloganeering by a good few decades. (Producer Michael Relph put it more flavourfully, describing the film as “a story not of glands but of love”.) Yet there’s a difference. While today, the emphasis on love over sex in queer-rights discourse is often a sanitising measure, calculated to meet straight sceptics at their emotional level, in Victim it’s an additional provocation, a suggestion that homosexuality runs deeper than the thrill of the illicit – and thus a more piercing threat to the social norms that a withering law was only barely holding in place.

In these respects, Victim is a film plainly made for a straight audience, patiently pleading for them to open their minds even if it means slightly patronising its gay characters (and potential viewers) in the process. A straight male audience at that, I should add: what’s perhaps most dated about Victim today isn’t its incidental homophobia but its pointed misogyny, as practically every female character (besides Syms’ wronged, simpering wife and Mavis Villiers’ haggish barfly) is a mouthpiece for society’s most viciously gay-hating views. Laura’s reward for standing by her man, meanwhile, is the promise of continued, sexless companionship: perhaps with the censors’ sensibilities, Victim’s noirish plot of fighting criminal homophobia bends itself into a pretzel so as to end on a scene of a man (a gay one, but no matter) declaring his undying need for his wife. Sixty years, in case you hadn’t noticed, was a very long time ago.

And yet. That Victim retains an exciting quiver of queer subversion comes largely down to an extraordinary performance by Bogarde – working on a different plane of suggestiveness and nuance from most of his co-stars, in no small part because he was acting out his own split between public and private life. One of cinema’s most defining queer stars, Bogarde himself never came out, even across multiple volumes of an autobiography that depicted his long-term romance with manager Anthony Forwood as the most intimately platonic male friendship imaginable. Bogarde simply had too much to lose by coming out, even after headlining Victim (in a role already turned down by the likes of James Mason and Stewart Granger by the time it came to him) forever cost the actor his clean-cut matinee idol status. It was the best thing that could ever have happened to him, cuing a succession of fascinatingly queer and queer-coded roles in off-kilter films – from Darling to Death in Venice, from The Servant to Despair – that shaped his screen legacy more than any of the straight romantic leads that came before.

His Farr, then, is an immaculate study of queerness hiding in plain sight, a crisp, brittle performance rich in self-isolating gestures and desirous gazes that go unnoticed by the straight men surrounding him: watch for the playfully approving smirk that brushes momentarily across his face when his investigations bring him to a household of three men, or the curious, cruisy feelers he puts out even when faced with the blackmailers’ most threatening heavy. (The thug favours tight leather and has a framed photo of Michelangelo’s David in his apartment: Victim isn’t always up to its leading man’s levels of subtlety.)

These are the intuitive, near-invisible signals that even the most gifted straight actors often fail to perform when cast in queer roles: one scene between Bogarde and the allegedly bisexual Dennis Price, as another targeted gay man, positively fizzes with mutual recognition and sparring empathy. It’s as a showcase of inclusive, game-recognise-game gay performance that Victim might be most enduringly, exhilaratingly fresh and unusual – even if the film, and its brilliant star, couldn’t claim as much at the time.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies