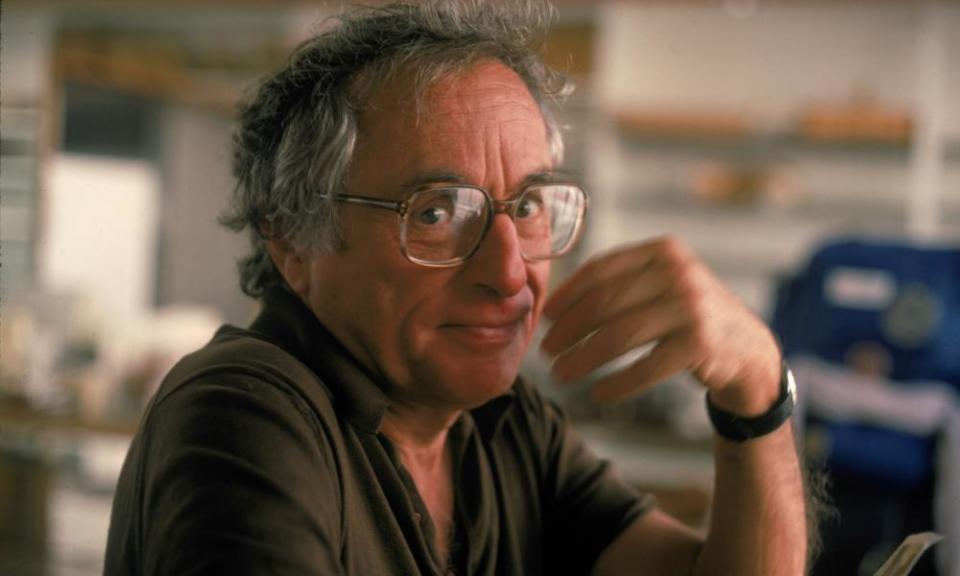

Walter Bernstein obituary

In Martin Ritt’s 1976 film The Front, Woody Allen plays an unassuming dolt who agrees to pose as the author of scripts written by blacklisted victims of the anti-communist McCarthy witch-hunts, which resulted in the hearings of the Huac (House Un-American Activities committee). Ritt himself was a survivor of the blacklist, as were several of his cast members, including the actor Zero Mostel and the film’s writer, Walter Bernstein, who based the Oscar-nominated screenplay on his own experiences.

Bernstein, who has died aged 101, joined the Young Communist League at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, in 1937 and the Communist party shortly after the second world war. His membership lasted until the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. The initial blacklist, of the so-called Hollywood Ten, occurred in 1947 when his screenwriting career was just starting. “I never thought it was going to affect me,” he told the Television Academy Foundation. “I was too respectable, too accepted.”

His name turned up three years later among the 151 listed in the anti-communist pamphlet Red Channels, alongside Lillian Hellman, Lena Horne, Arthur Miller and Edward G Robinson. For most of that decade, Bernstein continued working either pseudonymously or behind a series of “fronts”, who usually received around 10% of his fee. Bernstein’s uncredited work during this period included the television series You Are There (1953-55), which featured re-enactments of historical events.

The experience of being pursued by the FBI, as he described it in his 1996 book Inside Out: A Memoir of the Blacklist, was striking in both its menace and its mundanity. Waiting for a train, he was approached by “two men in cheap suits … One of them said, ‘Are you ready to talk, Mr. Bernstein?’ I shook my head and got into the train. The doors closed and the two FBI agents watched me as the train pulled away.”

On other occasions, they rifled through his bins or called at his home. “They would ring your doorbell … always two men, very polite. They’d say, ‘We want to talk to you.’ I said I had nothing to say and they went away.” He never got angry at them. “They were only doing their job, like delivering milk.” Nevertheless, there is no mistaking the relish in that scene at the end of The Front when Allen calmly confronts his persecutors on the Huac. “I don’t recognise the right of this committee to ask me these kinds of questions,” he says. “And furthermore, you can all go fuck yourselves.”

Bernstein was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Louis, a teacher, and Hannah (nee Bistrong), and educated at Erasmus high school. Immediately after graduation, he spent six months at the University of Grenoble studying French at his father’s insistence. When he returned to the US, he enrolled at Dartmouth and became film critic of the campus paper, the Daily Dartmouth, until he was sacked after disparaging Frank Capra’s 1937 film Lost Horizon.

He later wrote for the New Yorker and became a staff writer on the magazine. During the war, he scored a coup by becoming the first US correspondent to secure an interview with the communist leader and future dictator Josip Broz (who came to be known as Tito) while reporting for the army newspaper, Yank. Bernstein hiked for a week through the mountains of German-occupied Yugoslavia to find him.

Berstein’s early journalism was published in 1945 in the collection Keep Your Head Down. His Hollywood career began two years later with a 10-week contract at Columbia Pictures. He earned his first credit on the thriller Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), also known as Blood on My Hands, starring Joan Fontaine and Burt Lancaster, and worked behind the scenes on the political drama All the King’s Men (1949) while continuing to write for the New Yorker.

The grip of the blacklist loosened in the late 1950s, and Bernstein’s fortunes picked up when the director Sidney Lumet hired him under his own name to write That Kind of Woman (1959). He did uncredited work on the western The Magnificent Seven (1960) and scripted Lumet’s gripping cold war thriller Fail Safe (1964); his screenplay for the latter was also used as the basis for a version directed by Stephen Frears and starring George Clooney, which was broadcast live on US television in 2000.

His favourite among his own films was The Molly Maguires (1970), directed by Ritt, which dramatised the struggles of a group of 19th century Irish-American coal miners against their oppressive Pennsylvanian employers. He also wrote Semi-Tough (1976), a comedy with Burt Reynolds and Kris Kristofferson as football players, an adaptation of the Harold Robbins potboiler The Betsy (1978) and John Schlesinger’s wartime love story Yanks (1979), starring Richard Gere. He addressed the McCarthy era again in The House on Carroll Street (1987), about a blacklisted photo editor and the FBI agent who falls for her.

Bernstein’s only film as director was Little Miss Marker (1980), a 1930s-set comedy starring Walter Matthau and Julie Andrews, which he adapted from the Damon Runyon story previously filmed in 1934.

In 2011, he was co-creator with Ronan Bennett of the four-part BBC drama Hidden. Asked on the occasion of his 100th birthday what he was most proud of, Bernstein replied: “Holding onto my socialism, standing up for what I believed. I think I did that okay.”

He was three times divorced, and is survived by his fourth wife, the literary agent Gloria Loomis, and by five children: Joan and Peter, from his first marriage, to Marva Spelman; and Nicolas, Andrew and Jake, from his third marriage, to Judith Braun. His second wife was Barbara Lane.

• Walter Bernstein, screenwriter, born 20 August 1919; died 23 January 2021

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies