Archaeologists find ‘mind-blowing’ network of lost cities hidden in Amazon

Archaeologists have uncovered an “unprecedented” network of lost cities in the Amazon that shed light on how ancient civilisations constructed vast urban landscapes while living alongside nature.

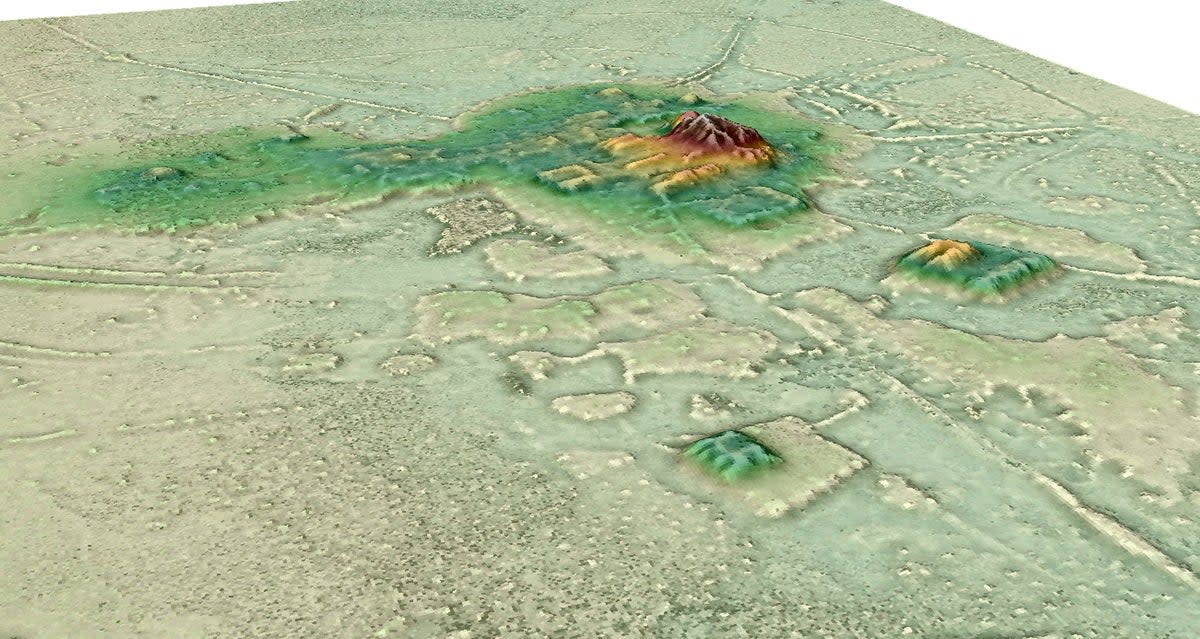

Researchers used lidar technology, dubbed “lasers in the sky”, to scan through the tropical forest canopy, and examine sites found in the savannah-forest of South West Amazonia.

They uncovered a wide range of intricate settlements that have laid hidden under thick tree canopies for centuries in the Llanos de Mojos savannah-forest in Bolivia.

The findings, described in the journal Nature on Wednesday, shed light on cities built by the Casarabe communities between 500 AD and 1400 AD.

Heiko Prumers, an archaeologist and study co-author from the German Archaeological Institute, said the complexity of these settlements is “mind-blowing”.

The site features an unprecedented array of elaborate and intricate structures “unlike any previously discovered” in the region, including 5m high terraces covering 22 hectares – the equivalent of 30 football pitches – and 21m tall conical pyramids, say the scientists, including Jose Iriarte from the University of Exeter in the UK.

Researchers examined six areas within a 4,500sqkm region of the Llanos de Mojos, in the Bolivian Amazon, that belonged to the Casarabe culture.

They also found a vast network of reservoirs, causeways, and checkpoints, spanning several kilometres at the site.

A @Nature paper reports the discovery of the archaeological remains of 11 previously unknown settlements of the Casarabe culture, which dates to around AD 500 to AD 1400, in south-west Amazonia. https://t.co/l2wpJnulSz pic.twitter.com/OPZpGtcb5I

— Nature Portfolio (@NaturePortfolio) May 25, 2022

These latest findings challenge the view of Amazonia as a historically “pristine” landscape.

Scientists say the region was instead home to early urbanism created and managed by indigenous populations for thousands of years.

One of the most fascinating features of the new discovery, researchers say, is that the urban settlements were constructed and managed not at odds with nature, but alongside it.

“We propose that the Casarabe-culture settlement system is a singular form of tropical agrarian low-density urbanism – to our knowledge, the first known case for the entire tropical lowlands of South America,” scientists wrote.

They say the indigenous populations employed successful sustainable subsistence strategies that promoted conservationism and maintained the rich biodiversity of the surrounding landscape.

“We long suspected that the most complex pre-Columbian societies in the whole basin developed in this part of the Bolivian Amazon, but evidence is concealed under the forest canopy and is hard to visit in person,” Dr Iriarte said.

“Our lidar system has revealed built terraces, straight causeways, enclosures with checkpoints, and water reservoirs. There are monumental structures just a mile apart connected by 600 miles of canals, long raised causeways connecting sites, reservoirs and lakes,” he explained.

Scientists say the findings “can significantly contribute” to perspectives on the conservation of the Amazon.

“This region was one of the earliest occupied by humans in Amazonia, where people started to domesticate crops of global importance such as manioc and rice. But little is known about daily life and the early cities built during this period,” Dr Iriarte said.

The lidar analysis revealed that the core of the settlements spread over several hectares, on top of which lay civic-ceremonial U-shaped structures, platform mounds and 21m tall conical pyramids.

Crucially, scientists say the scale of labour and planning to construct these settlements has no precedent in the Amazonia region. It is instead comparable only with the archaic states of the central Andes.

The findings suggest the indigenous populations transformed Amazonian seasonally flooded savannas, roughly the size of England, into productive agricultural and aquacultural landscapes.

“Our results put to rest arguments that western Amazonia was sparsely populated in pre-Hispanic times. The architectural layout of Casarabe culture large settlement sites indicates that the inhabitants of this region created a new social and public landscape,” Mark Robinson, another co-author of the study, said.

The findings provide evidence of successful, sustainable subsistence strategies, and a previously undiscovered cultural-ecological heritage, researchers say.

“The scale, monumentality and labour involved in the construction of the civic-ceremonial architecture, water management infrastructure, and spatial extent of settlement dispersal, compare favourably to Andean cultures and are to a scale far beyond the sophisticated, interconnected settlements of Southern Amazonia,” Dr Robinson added.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News