Barbara Hershey: ‘If we treat the elderly like children, they start acting like children’

When she was little, Barbara Hershey would fall asleep staring at the local paper, imagining the personal lives of those immortalised in black-and-white print. The future star of Beaches and The Last Temptation of Christ would pretend to be the Wicked Witch of the West, and turn the garden of her parents’ Hollywood home into her personal theatre stage. All of it would be in secret, though, lest anyone saw her be anything but happy.

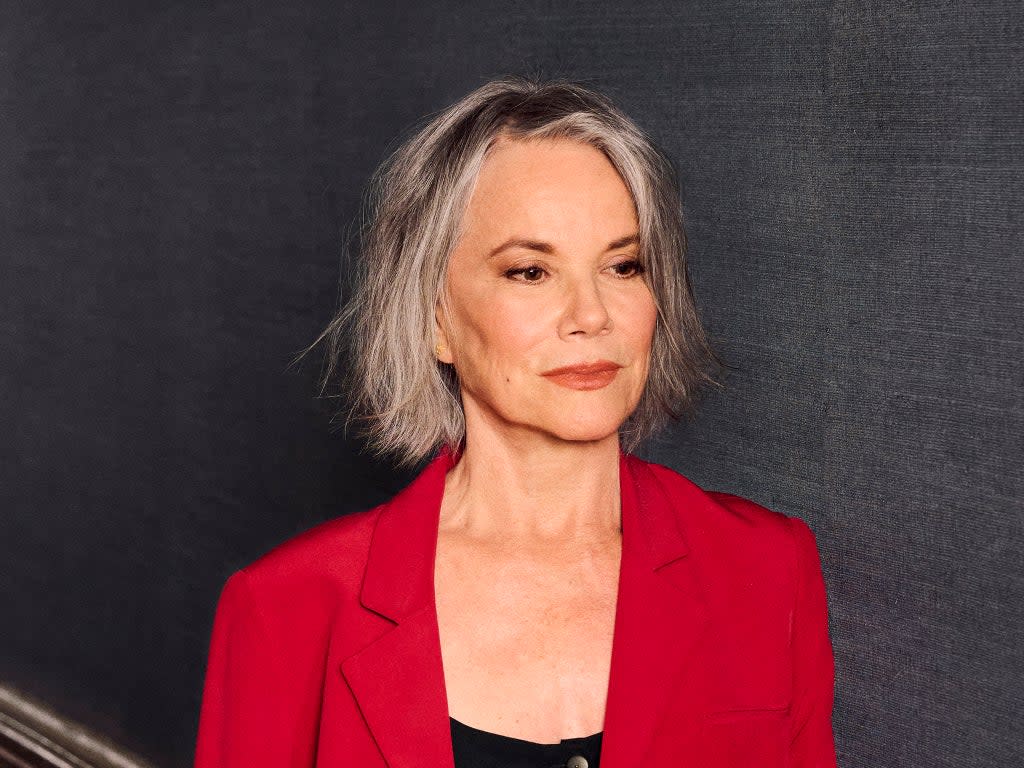

“I had a very repressed childhood,” says the 73-year-old, gazing up towards her Zoom camera from her house in Los Angeles, her hair cut into a sleek, black-grey bob. “I wasn’t allowed to express anything negative. So I’d go out into the backyard, and I’d act out anybody. I could express anything in that world. It was a safe place to do it, and I wouldn’t get hurt.”

Those hemmed-in beginnings also help to unlock everything that came next. Once Hershey fled home at 17 to become an actor, she ran head first into the bohemia of the late Sixties and early Seventies, seeking freedom and personal enlightenment. In the Eighties – a decade in which her face seemed to permanently decorate billboards, bus shelters and cinema facades – she would become as fierce a screen presence as she was inscrutable. Hers was a kind of ambiguous steeliness; she always seemed to play roles that hinted at great complexity beneath a formidable veneer. Think of her as Sam Shepard’s gutsy life partner in The Right Stuff (1983), or the sensitive and searching sibling in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Even the sunny wife-and-mother of Beaches (1988) was secretly wounded, cold there – as the song goes – in the shadow of her famous BFF (Bette Midler). All of Hershey’s characters seem to arrive as one thing before becoming something else. She’s a bit like that in reality, too, at first business-like and slightly guarded, but growing looser over the course of the conversation.

Across her eventful 53-year career, she’s experienced more twists and turns than many of the films she’s been in. Finally nominated for an Oscar in 1997 for Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady – two decades after many in the industry had written her off – she has recently become a regular in the horror space. Black Swan (2010), in which she played Natalie Portman’s broken and tyrannical mother, proved she could be terrifying. She’d replicate that ruthless menace as an evil queen in the fairytale series Once Upon a Time, and gave good panic as a terrorised grandma in the Insidious movies. Now she can be found doing the same in The Manor, a supernatural thriller that debuted on Amazon Prime this week. “I like dealing with the dark side,” she says. “I think we were equipped as primal cave people to have fear, and I think horror is a safe arena to explore it.”

In The Manor, Hershey plays a woman who moves into a sinister retirement home after a stroke, only to be faced with unusual fellow residents and a demon at the foot of her bed. Beyond the spookiness, it touches on a number of hot-button topics: plastic surgery, the elderly and infirm of the world being shoved out of sight, and the messier realities of getting older. Hershey herself isn’t quite as fatalistic about it all, but admits to being affected.

“I’m a victim of the prejudice,” she says with a smile. “Not that I’m a victim, but I have to deal with it. I always say that I’m not afraid of ageing – I’m afraid of other people’s reaction to my ageing. I’ve witnessed nursing homes and how they treat people, and how we treat older people. If we treat them like children, they start acting like children. Our society isn’t very kind to people as they get older.”

The film also reunites Hershey with actor Bruce Davison, her co-star in the heated cult classic Last Summer (1969). Hershey, then just 19, played a sociopathic teenager involved in a love quadrangle with two surfers and a timid outsider. Hershey says that director Frank Perry originally wanted her to play the outsider – a role she knew and understood well – but she insisted she play “the scary part” instead. “At that point in my life, I had never said a swear word, and here I am playing this provocative girl who takes off her top and I was the complete opposite of that,” she remembers. “It was so fascinating to find that in me.”

It also revealed a tremendous degree of early empathy. She sought out the “scary part” in order to dive into someone totally unlike herself. “Once I played that character in Last Summer, whenever I bumped into a girl like that in my life, I knew her,” she says. “I knew her fears, I knew her vulnerabilities. I knew what she was crusty about. The honour of acting is it expands you as a human being.”

That empathy extended beyond humans. While she was filming a scene in Last Summer, a seagull was accidentally killed, and Hershey told The New York Times in 1973 that she felt its “soul enter me”. As a form of tribute, she changed her name to Barbara Seagull, and it is under that name she’s credited for at least four movies in the Seventies. A lot of mockery followed. Hershey’s movie career stalled.

When Hershey mounted a comeback in the early Eighties, she would bristle at questions about her experiences in the Seventies. She would also avoid a lot of interactions with the press. Lost in the slight hysteria over the seagull, though, was Hershey’s sincere nonconformity. She embraced the freedoms of the flower-child era in a way that her detractors were perhaps too scared to. And don’t Hershey’s twenties seem somewhat enviable now? To be young, expressive and curious, and living amid the offbeat hubbub of California’s Laurel Canyon, in the same house that James Taylor and Carole King once did yoga in?

Hershey tightens a little upon mention of that time, a kind of “here we go again” shadow falling over her face. “That’s the danger of 50 years of acting,” she cracks. “You grow up publicly.” Still, she understands the curiosity. “It’s the difficulty of doing what we’re doing right now,” she says, gesturing towards her camera lens. “Lots of times, there are people who are less sensitive and they just want a sound bite or they just want something that’s sensational that they can write about. They sensationalise your life, which is a really private thing and a really much more complex thing. So you get misunderstood.”

She admits that she used to be naive around journalists. “I’ve never been a very knowledgeable person in terms of the press. Even as a little girl, my dream wasn’t the red carpet – it was always acting. I’ve always been awkward. I’ve learnt, you know, that you’re all people and I’ve learnt to actually…” She pauses briefly, and sits back. “I’m actually curious about you in a way that is different than I used to be. I’ve relaxed more. But there’s a danger of being interpreted in a negative way for something that thousands of teenagers go through. Because you’re known, it’s interpreted in this negative way and that’s hard. To be a symbol of something at any stage of my life never interested me. I’m too private for that.”

She prefers, she says, to talk about her work, which we do. I mention that a colleague learnt to recite whole scenes from Beaches by heart, purely because they were made to watch it so often as a child. She howls with laughter. “You know, I’m told things like that a lot,” she says. Beaches wasn’t just a movie about two lifelong best friends – one of whom is diagnosed with the most photogenic terminal illness imaginable – but seemed to invent an entire genre of glossy studio films about women’s inner lives.

“It was a great experience, but I was aware that it was an unusual thing at the time to make a film about female friendships,” Hershey says. “You do a movie about two men, and it’s called a film. You do a movie about two women, and it’s called a chick flick, which I really found offensive. When it came out, it wasn’t particularly reviewed well, and I don’t think it did particularly well at first, but it’s had this resonance. Friendships between women matter, and it’s a legitimate world to make a movie about. It’s sad that that’s unusual.”

Beaches was released the same year as Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, in which Hershey played Mary Magdalene. A daring, disquieting and – according to some – blasphemous story of Jesus as a man consumed by doubt, anger and lust, it is the film Hershey holds most dear. She had given Scorsese a copy of Nikos Kazantzakis’s controversial bestseller years earlier, on the set of Boxcar Bertha, the filmmaker’s second movie. That The Last Temptation of Christ faced ludicrous amounts of backlash upon release, following an arduous shoot, is what made it such a rewarding experience.

“Marty wanted to make a film that people would talk about over coffee afterwards,” Hershey recalls. “But it was so misunderstood. Ten thousand people marched on Universal Studios and burnt effigies of [studio head] Lew Wasserman. A theatre in Paris got firebombed.” She shakes her head. “Things happened that had nothing to do with the film itself. I think in retrospect – with distance – people have seen the film for what it is and not the controversy. But it took years for that to start happening.”

It’s a bit like that seagull, or ageing in the public eye – once people calm down about it, it’s a lot less dramatic than it first seemed.

‘The Manor’ can be streamed on Amazon Prime now

Read More

Joan Allen: ‘John Malkovich or Nicolas Cage? I think they’re on an equal plane of eccentricity’

James Caan: ‘I was always cast as Mister Tough Guy – they wouldn’t let me do much else’

Sophia Loren: ‘I’ve always tried to play women with a strong character’

Todd Haynes on Velvet Underground: ‘Everybody was objectified at Warhol’s Factory’

Comic books are doing everything superhero films aren’t for queer representation

Jake Johnson: ‘I like tripping out under hypnosis and rewriting history’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News