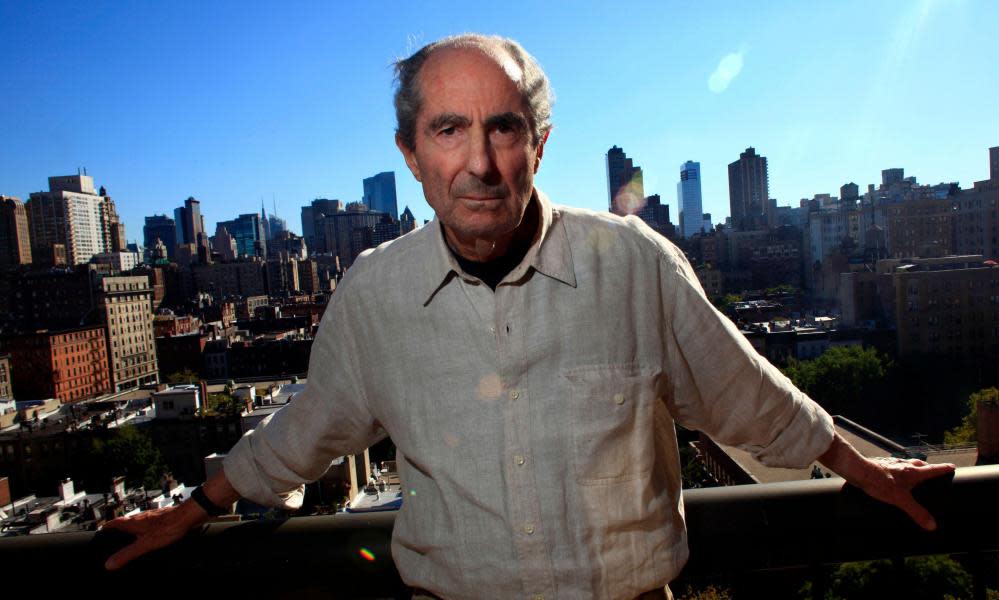

A new biography ‘unveils’ Philip Roth as a misogynist. Tell me something I don’t know

In order to grow up, as Sigmund Freud probably wrote somewhere, a child must rebel against its parents, and for a while now modern culture has been rebelling against its literary fathers, that Mount Rushmore of 20th-century highbrow masculinity: Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, John Updike and Philip Roth. Last month, two British newspapers announced that Roth “could face getting cancelled” on account of details about his personal life included in two new biographies. That Roth arguably cancelled himself three years ago by dying is beside the point: the quickest way to prove one is Good these days is to vilify those who are Bad, and death is no hiding place.

Since their deaths, all of these men have come in for criticism, mainly for their attitudes towards women: Mailer was hugely popular at his peak, but now he’s probably best known for that whole stabbing-his-second-wife awkwardness; Updike is regularly derided as “a misogynist”; and Bellow’s female characters are often, at best, thinly drawn, or full-on bitches and shrews. Now, inevitably, it’s Roth’s turn.

“New biographies of the Great American Novelist highlight Roth’s predatory behaviour and obsession with sex,” read one headline, although as headlines go, “Philip Roth was obsessed with sex,” is pretty much up there with “The royal family are snobs.” Who’d have guessed such a thing of the man who wrote one novel about extreme masturbation (Portnoy’s Complaint) and another about a man turning into a giant breast (The Breast)? As for his behaviour with women, you don’t need to read the new biographies to learn about that. Roth’s ex-wife, Claire Bloom, wrote about their relationship in her memoir, Leaving A Doll’s House, 25 years ago. You could also read Roth’s not-exactly-contrite reaction to Bloom’s complaints, his 1998 novel, I Married A Communist, in which the protagonist’s vicious wife was clearly based on Bloom.

This side of these authors hardly went unnoticed in their lifetimes. Second-wave feminists including Kate Millett and Germaine Greer took on Mailer, and David Foster Wallace described Updike as “a penis with a thesaurus”. Roth anticipated his posthumous destiny in his 2007 novel, Exit Ghost, in which his long-term protagonist, Nathan Zuckerman, rages against prurient biographers who tear down the reputations of the dead. So the stories aren’t revelatory – but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be re-examined. They are not irrelevant, but are they the full story?

Related: I love awards ceremonies – but losing on Zoom is another story | Hadley Freeman

I was never a Mailer fan, but I went through a Roth and Bellow phase after university, as a reaction against the entirely English (and goyish) focus of my literature degree. Roth’s American trilogy is probably my favourite of all these books, and in those his libido is largely in the shadows. This is not something that can be said about my second-favourite series, Updike’s Rabbit books. But enjoying a novel is not dependent on approving of the deliberately flawed characters, or its similarly imperfect author. There are many things that make a book good – elegant writing, emotional truth, narrative voice – besides its morality. “Roth’s misogyny infuses everything that he writes,” according to Meg Elison, a novelist recently described by the Times as “re-examining Roth”. This is typical of the all-or-nothing approach that is popular today, where if you don’t like everything about a public figure, then you can’t like anything.

“Looked at from the point of view of today, Roth’s books are on the wrong side of MeToo,” Sandra Newman, an American novelist, has said. Looked at from the point of view of today, every single thing from the past is on the wrong side of the modern moment, because that’s how time works. I hate to break awkward news here, but I don’t think too many of Charles Dickens’s novels pass the Bechdel test. Looked at from the point of view of today, The Merchant Of Venice is on the wrong side of a lot of things – but it’s still a terrific play.

I didn’t always enjoy the lust and the rage in Roth’s books, and I probably love his poignantly historical books (American Pastoral, The Plot Against America) more than the unremittingly sexual ones. Books can reflect the times in which they were written, but they also show us the author, and no one can accuse Roth of ever hiding who he was: American, Jewish, obsessed with sex, obsessed with death, funny, angry, wise, profane, imaginative, cruel. That is what readers always liked about him. Reducing him to one aspect of his biography is like reading the York Notes version of his books. There is a difference between reckoning with the past, and seeing only one colour of the rainbow.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News