Cate Blanchett turns in a virtuoso performance in TAR , Amsterdam makes some rookie moves

Amsterdam

In theaters now

Merie Weismiller Wallace, SMPSP/20th Century Studios

There are no small actors in Amsterdam, just a blizzard of stars and wham-bam cameos — Chris Rock, Mike Myers, Taylor Swift — dancing as fast as they can to the beat of David O. Russell's strained, hectic, and often inscrutable caper. It's impossible to say whether the movie, based on a real-life plot to overthrow the U.S. government, is meant to be a comedy, a murder mystery, or maybe even a thwarted musical; more than once, the characters on screen do break into song. But it feels like a lot of fanfare and celebrity flop sweat to invest in the film's minimal returns, and a peculiar swerve for Russell after a seven-year absence from the screen. (Following the full-court blitz of The Fighter, Silver Linings Playbook, and American Hustle, his last project was the deceptively named Jennifer Lawrence home-shopping biopic, Joy, in 2015.)

It's early-1930s Manhattan, more or less, and best friends Burt Berendsen (Christian Bale) and Harold Woodsman (John David Washington) still bear the marks of their time together in the trenches of WWI — Burt, with his glass eye and back full of shrapnel scars, Harold with a deep gash across his otherwise unblemished jawline. One day, a damsel in distress (Swift) bursts into Burt's office, insisting that the recent death of her war-hero father, Sen. Bill Meekins (Ed Begley Jr.), did not come by natural causes, and that only this motley duo, both former soldiers under his command, can crack the case.

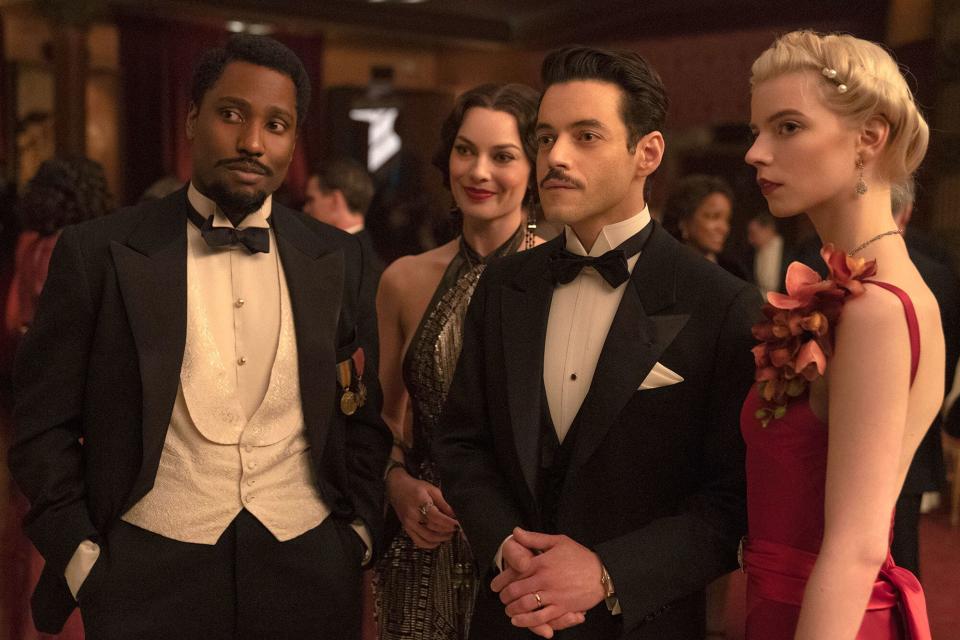

Neither of them are P.I.'s, but they try their best — with the help of a sympathetic friend in the coroner's office (Zoe Saldaña) and Harold's less-than-enthused legal associate (Rock) — to track down the root of what turns out to be a vast conspiracy, in which they themselves have already become suspects. Matthias Schoenaerts and Alessandro Nivola play two not particularly bright NYPD detectives in pursuit, and Rami Malek and Anya Taylor-Joy a daffy pair of married aristocrats who may have a clue; Margot Robbie is the combat nurse who was once Burt and Harold's favorite co-conspirator, and also Harold's lover. Together, they had a wild run in post-war Amsterdam before the social and economic realities of life brought their dreamy Dutch idyll to an end.

Robert De Niro, barely bothering with his line readings, drops in as a decorated general, and Myers and Michael Shannon are suitably surreal as a pair of eccentric intelligence agents chewing their little bits of scenery into a fine pulp. There's an unexpected pleasure in hearing Malek roll the words "graham cracker" across his tongue, and the production and costume design are impeccable. But the resolution of the central mystery is both rushed and obtuse, and it all unfolds in a frenetic, flailing whirl of pomp and nonsense that Amsterdam's strange, circuitous journey and almost embarrassing surplus of stars never quite justify: a whirring music-box curiosity in search of some elusive purpose, and a point. Grade: C+ — Leah Greenblatt

Triangle of Sadness

In theaters now

Neon

Money talks, and beauty walks — it dips and spins, twirls and sashays, and stares lovingly into its own void — in Triangle of Sadness, an acid, sun-drenched satire from the incurable Swedish provocateur Ruben Östlund. The celebrated director of The Square and Force Majeure has two near-perfect muses in Harris Dickinson and Charlbi Dean as Carl and Yaya, a fashion-model couple whose almost obscene aesthetic symmetry doesn't necessarily translate to their relationship. He's gorgeous and needy, a paragon of talky Gen Z anxiety; she's gorgeous and a little bit ruthless, a social Darwinist with a low tolerance for Carl's constant tsunami of feelings.

Somewhere in between bookings, they've accepted a trip on a luxury super-yacht — Yaya's also an influencer, so it's all expenses paid — and made enough peace to carry on for a while, as long as Carl stays obligingly quiet and takes all the "casual" bikini snaps she needs for her feed. The other guests are mostly older, and more accustomed to the dividends of extreme wealth. The bright-eyed staff who serve them all, overseen by a diligent ice-blonde manager called Paula (Vicki Berlin), are accommodating to a fault: No detail is too small, no guest request too petty or outrageous to be met. But what's going on with the captain (Woody Harrelson)? He won't come out for dinner in his dress uniform, and there's a whole lot of liquor bottles and old socialist literature clanging around in his quarters.

Harrelson, once he emerges, looks like he hasn't enjoyed himself this much on screen in a long time, though it's better to know as little as possible about what transpires after the movie's midway point — except that there's a reason little airsick bags were left, winkingly, on every chair in early press screenings. (The story behind the title, too, is too good to spoil, though the explanation for that comes gratifyingly early on.) The tone and setting shift significantly in the film's back end — it's meant to be jarring, and it is — but that narrative swerve also gives Filipina actress Dolly de Leon a chance to shine as Abigail, a middle-aged custodial worker on the ship who may have a better read on Machiavelli and trade economics than anyone.

Hers is the kind of stealth performance that awards-season breakouts are made of, and Dickinson and Dean are consistently fun as archetypes whose flaws are actually articulated; they're messy, mercurial canvases for the director, not just beautiful blanks. (Dean died suddenly last month at 32, which adds a strange bittersweet postscript to her presence here.) Östlund's sense of irony can sometimes veer toward the obvious or flat-footed. His targets — the self-regarding follies of the uber-rich, the inanity of social media, beauty as currency — are so broad and shiny that the occasional dip feels almost inevitable. But Triangle hits more marks than it misses, and in a somber, often underwhelming season of would-be arthouse hits, the movie is a bona fide trip: not the funhouse mirror we need for these ridiculous times, maybe, but one we deserve. Grade: B+ — Leah Greenblatt

A Friend of the Family

(Streaming now on Peacock)

Erika Doss/Peacock Jake Lacy and Hendrix Yancey in 'A Friend of the Family'

A Friend of the Family begins with a message from the real woman at its center, Jan Broberg. "I want to tell my family's story today, because so many seem to think that something like this could never happen to them," she explains. Broberg lived through a stunning, strange, awful ordeal, and the life she's built as a survivor of kidnapping and sexual abuse is incredibly admirable. Less impressive is Peacock's nine-episode adaptation of her story, which — like so many other recent true-crime dramas — is a competent reenactment devoid of any deeper analysis.

When Robert "B." Berchtold (Jake Lacy) moves to Pocatello, Idaho, in the early '70s, he and his family are welcomed warmly by fellow Mormons Mary Ann (Anna Paquin) and Bob Broberg (Colin Hanks), who live down the street. Brother B. takes a special liking to young Jan Broberg (Hendrix Yancey) and spends the next several years building up her trust — while simultaneously working his seductive charms on Mary Ann and ultimately manipulating Bob into a compromising situation of his own. The Brobergs, like most Americans, had never heard of "grooming" or the term "pedophile," so even when B. took Jan horseback riding in the fall of 1974 and failed to bring her back for weeks, it was almost impossible for them to fathom the monster their family had been living with for years.

The ensemble is solid: Lacy gives good sociopath, morphing from buttery smooth to icily menacing with a shift of his gaze, while Hanks conveys Bob's stoic repression as B. alternately emasculates and enrages him. Yancey brings an authentic sweetness and vulnerability to tween Jan, as does Mckenna Grace (The Handmaid's Tale), who plays her as a teen.

Created by Nick Antosca (Candy, Brand New Cherry Flavor), A Friend of the Family isn't out to judge or defend Mary Ann and Bob, who make some startlingly naïve decisions about B. and their daughter. But the show also doesn't do much in the way of examining the Brobergs to determine what may have led them to be so susceptible to Brother B.'s sinister machinations. It's understandable why the real Jan Broberg continues to tell her story; she previously participated in the 2017 documentary Abducted in Plain Sight. But what does Antosca want us to know? There's a vague nod to the patriarchal (read: sexist) structure of the Mormon church, perhaps to imply that both Mary Ann and Jan were conditioned to obey a trusted male friend. That's certainly not enough insight to sustain nine episodes of television, but in this era of true-crime awards bait, it'll have to do. Grade: C+ —Kristen Baldwin

TAR

In theaters now

Focus Features

Are all great artists necessarily great monsters, or is that just a story we've told ourselves for too long? The vectors of ego, talent, and personal liability collide in Todd Field's TÁR, a towering monolith of a movie rooted in an extraordinary, shattering performance by Cate Blanchett. She's Lydia Tár, whose success has earned her a rare kind of cultural cachet for a classical-music conductor: People pay just to watch her speak about her EGOT or her thoughts on Mahler, and moguls and doe-eyed groupies alike compete for the pleasure of her company. Her world is Gulfstreams and hushed hotel suites and a kind of severe, understated luxury. (The devil wears Margiela, probably.)

Lydia also has a partner, Sharon (the great German actress Nina Hoss), and a young daughter in Berlin, where she leads the city's world-class orchestra. Their domestic life, cosseted as it is in their plush townhome and the day-to-day of intra-office politics (Sharon is also her lead violinist), still contains a certain wariness: The pills Lydia urgently swallows when no one is looking aren't hers, and her interest in a new cellist, a brash Russian girl named Olga (Sophie Kauer), seems less than strictly professional. In fact she has a history of shining her light on pretty young women in the industry, and of withdrawing those affections in ways that don't always end well.

But when a former mentee of her own commits suicide, questions of culpability and undue intimacies begin to spill over in ways that her long-suffering assistant (Portrait of a Lady on Fire's Noémie Merlant) and the orchestra's press department can no longer contain. These are the bare outlines of the script, though what unfolds in the film's nearly two-hour-and-40-minute runtime defy almost any kind of easy summation. Field — whose two previous films, 2001's In the Bedroom and 2006's Little Children, earned eight Academy Award nominations between them — took 16 years to make TÁR, and it feels very much like a magnum opus. His story is so masterfully formed and Lydia's world so wholly, viscerally realized that the movie becomes a sort of profound immersive experience; whatever the opposite of sensory deprivation tank is, this is it.

Even the supporting parts are stupendously acted: Mark Strong as a fellow conductor who yearns to take Lydia's genius and cover himself in it like a balm; Hoss, who does more with her eyes in one devastating scene than most actors can do with their whole toolbox. Still, the movie belongs to Blanchett, in a turn so exacting and enormous it feels less like a performance than a full-body possession. That she slips often into fluent German and plays professional-grade piano in the film, among other things, is exceedingly impressive (watching her conduct, it feels like lightning might actually shoot out of her fingertips). But Lydia isn't a series of tricks and tics. She's a superstar and a virtuoso who has forgotten, perhaps, that she is also human — and that news comes for us all. Grade: A — Leah Greenblatt

Luckiest Girl Alive

On Netflix now

Sabrina Lantos/Netflix

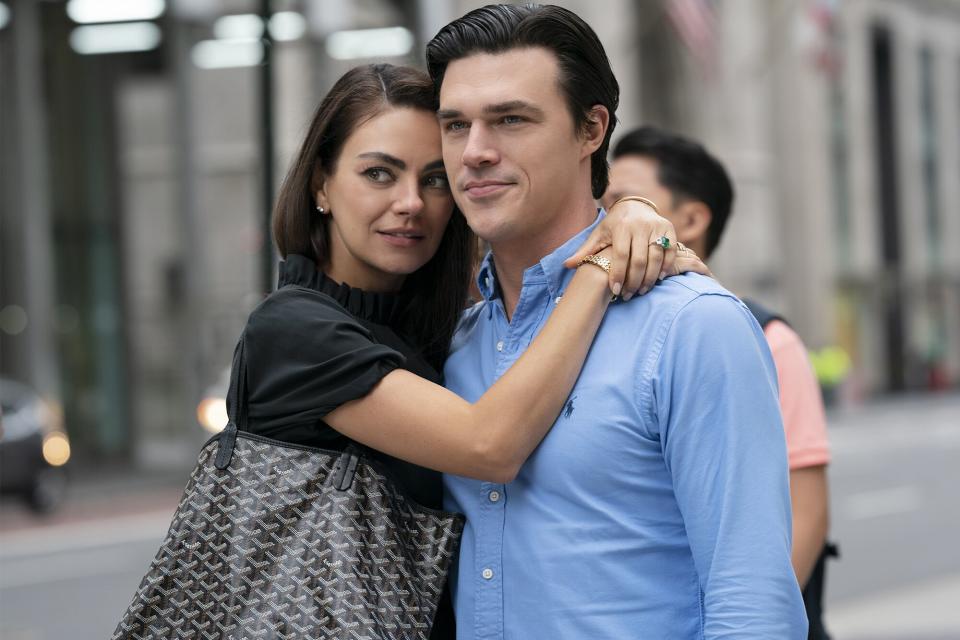

Luckiest Girl is the kind of rainy-day thriller Netflix was made for: lurid, entertaining, patently silly. It's also kind of a mess, though at least some of that likely comes from condensing the busy, grisly events of a best-selling book into less than two hours of screen time. There's almost no hot-button topic Jessica Knoll's 2015 novel didn't touch: gang rape, disordered eating, a deadly school shooting. Here, Knoll and director Mike Barker (The Handmaids Tale, Fargo) have adapted it into a barbed melodrama starring Mila Kunis as Ani FaNelli, a woman defiantly living her best Manhattan life. She has it all: the handsome old-money fiancé (Finn Wittrock), the Tribeca penthouse, the glossy media job, the lean pilates body.

She's also furious all the time, and still deeply traumatized from her experience as a scholarship kid at an elite prep school notorious for the Columbine-style massacre that, some 15 years later, an eager documentary filmmaker (Dalmar Abuzeid) is pressing her to address on camera. Flashbacks reveal a teenage Ani (Cruel Summer's Chiara Aurelia), then known as Tifani, and the cycle of acceptance and abuse she learned to tolerate as a not-skinny, not-rich outsider amongst her privileged peers, culminating one night in a brutal sexual assault. Barker shoots those scenes with bruising realism, though the overarching tone of the film is both soapy and slick — full of the outrageous machinations and familiar archetypes of a prime-time network drama, but without an FCC to censor its vigorous f-bombs.

Connie Britton, in several wigs, is stuck playing Ani's gaudy working-class mother, a woman whose ambitions for her daughter easily outstrip her empathy, and Jennifer Beals gets too little screen time as the lady-boss editor in chief who promises to bring Ani with her once she leaves the blow-job surveys and punny cover lines of their Cosmo-esque publication for more prestigious shores. (Drink any time Ani beatifically repeats the phrase "New York Times Magazine," and you might actually die by the final credits.) Kunis has to play a character so brittle and guarded and self-destructive that she verges on villainy, but the actress is sharp enough to make Ani-Tifani stick, even as the story wends towards its increasingly preposterous ending. Girl isn't a great movie or even a good one, really, but it has Kunis kicking her stiletto through a taxi-cab window and quoting William Faulkner, and it's right there in your queue. Will you really say no? Grade: B– — Leah Greenblatt

Want more movie news? Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free newsletter to get the latest trailers, celebrity interviews, film reviews, and more.

Related content:

Yahoo News

Yahoo News