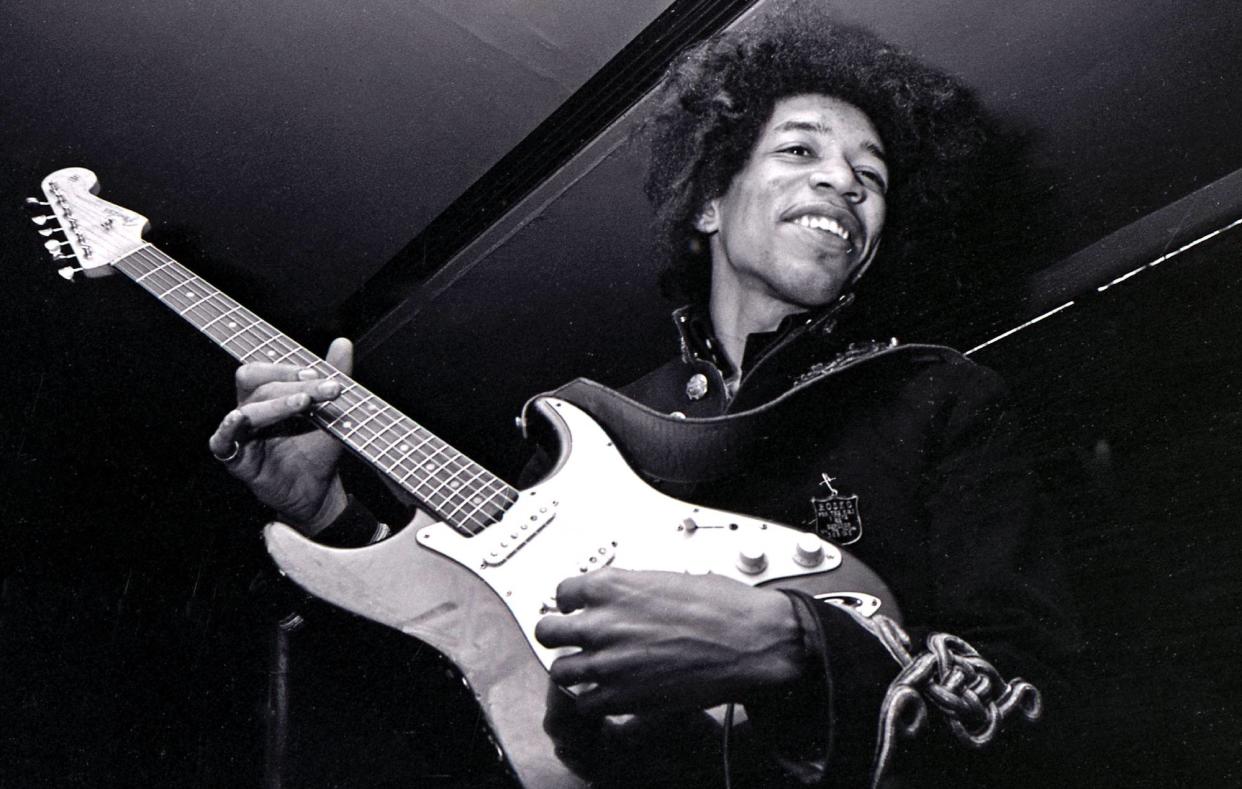

Celebrating Jimi Hendrix’s style on his 80th birthday

Like a peacock in a parade of penguins, Jimi Hendrix cut a dash on the streets of Soho in the late Sixties. Six-foot-plus tall, slender as a drumstick, scarves tied around his limbs billowing in the wind, his outfit a riot of clashing prints and touch-me velvets and silks – Hendrix was the walking embodiment of the era.

But it wasn’t always so. Growing up in Seattle, it was a chaotic and impoverished childhood, with siblings taken into care and an absent mother. Hendrix’s hand-to-mouth existence meant he was decked out in mismatched hand me downs and holy shoes patched up with cardboard inserts. And following a brief a stint in the military, Hendrix soon found himself signing up for a similarly rigid scene as a backing musician for some of the great stars of the time, including Curtis Knight and the Isley Brothers.

It was swiftly apparent that Hendrix was woefully ill suited to playing second fiddle, with the young guitar slinger routinely upstaging the main act. During a stint playing with Little Richard’s band, Hendrix and a colleague decided to venture off the style script and don flamboyant shirts instead of the prescribed uniform of buttoned-up matching suits, shiny shoes and slicked back, processed hair. It went down like a lead balloon. “I am Little Richard. I am the only one allowed to be pretty. Take off those shirts!” Little Richard berated them in a fit of rage.

While Hendrix was honing his craft as a jobbing musician on the Chitlin’ Circuit, a network of music venues used by Black performers during the racially segregated 1960s, it became an increasingly tough gig emotionally. “All those photographs you might have seen of me in a tuxedo and a bow tie playing in Wilson Pickett’s backing group were me when I was shy, scared and afraid to be myself. I had my hair slicked back and my mind combed out” he later reflected.

Luck came calling when Chas Chandler, English bassist for The Animals, spotted Hendrix onstage in a dingy New York club and signed up as his manager. First stop was relocating to Britain. In 1966, boarding the flight with a small bag containing a set of hair curlers and some acne medication, the artist born Johnny Allen Hendrix used the flight time to rename himself Jimi Hendrix and set about carving out a new identity; one that was finally all about self-expression.

Stepping off the plane, fashion-led London was perfectly ripe for Hendrix’s arrival. Just a couple of months prior, Time magazine in the US had published their ‘Swinging London’ cover story, declaring “The city is alive with birds (girls) and Beatles, buzzing with Mini cars and telly stars, pulsing with half a dozen separate veins of excitement.” The Summer of Love loomed large on the horizon.

“He was the right person at the right time” says Claire Davies, deputy director at Handel & Hendrix London, a Georgian townhouse in Mayfair’s Brook Street that both Jimi Hendrix and the German composer George Frideric Handel have called home, since immortalised as a museum. “London was in a post-war hangover, with a dreary dullness. But there was this counter culture emerging that brought colour and meaning back into the soul of culture”.

It helped that Hendrix wasn’t imitating American blues musicians, he was the real deal. While his British counterparts listened to BB King in suburban bedrooms, Jimi had played live with the King of the Blues, further adding to his kudos. “People saw Jimi as more legitimate than someone like Eric Clapton” Davies explains. Hendrix had also picked up tricks of the trade back in America, having seen Butch Snipes let loose and play the guitar with his teeth in Tennessee. “Down there you have to play with your teeth or else you get shot. There’s a trail of broken teeth all over the stage” Hendrix later quipped.

Teaming up with British musicians Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums, the Jimi Hendrix Experience was formed and the band hit the road running. A relentless touring schedule saw them gigging everywhere from end of the pier seaside towns to spit-and-sawdust working men’s clubs – letting loose at the Chelmsford Corn Exchange to a baffled crowd of clean-cut Mods, playing the sweaty caverns of Chislehurst Caves in Kent, while also performing at achingly hip London venues, including The Scotch of St. James and The Bag O’Nails.

On one tour, Jimi Hendrix – psychedelic rock god incarnate – bizarrely found himself sharing the bill with the British crooner Engelbert Humperdinck. On another, the squeaky-clean pop band The Monkees. They’d pit stop at greasy spoon cafes while on the road, where, decked out in full Experience regalia, the band were frequently greeted as if the Martians had finally landed.

But the legwork paid off and Hendrix was soon a darling of the British music scene, with three hits charting in the top ten within just a couple of months of arrival. The charismatic performer was the hottest ticket in town, stunning British audiences with seductive shows that frequently climaxed with setting his guitar ablaze. Fellow musicians were reduced to tears at the beauty of Hendrix’s electric guitar wizardry, some storming out in defeat as the game was finally up.

Offstage, Hendrix tried his hand at acclimatising to British culture, downing cups of tea and watching Coronation Street. But it was the quirky boutiques and clothing markets that really captured his imagination, and again, his timing was impeccable. The recent boom in travellers on the hippie trail – an overland route taking in destinations such as Turkey, Iran and India – meant that London was awash with an eclectic mix of textiles and styles.

On the Kings Road, Hendrix ducked behind the beaded glass curtain at Granny Takes A Trip to browse rails of hallucinatory floral prints. On the Portobello Road he headed to I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet, a boutique specialising in upcycled tailoring and antique military jackets from Britain’s imperial past. Fellow shoppers included Mick Jagger and John Lennon; who would soon incorporate the look into the album cover for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

As a former paratrooper, the army tunics resonated deeply with Hendrix. Although he claimed publicly to wear them out of respect, with the heightened anxiety surrounding the Vietnam War, many read them as a political anti-war statement. His signature style became the iconic Hussar jacket, embellished with gold braiding and fur trim. “It conjures up Psychedelia meets Victoriana. For an American, he really married the ever-so-British King’s Road aesthetic with Sgt. Pepper styling” notes designer Wayne Hemingway.

Hendrix took a deep dive into London’s bewildering dressing up box and somehow came up for air with a cohesive style. Men were just starting to occupy the erotic gaze, rejecting the orthodoxies of standardised masculinity and experimenting with clothing previously reserved for women. For Hendrix, this meant mixing military jackets with lace and velvets, embroidered Afghan waistcoats with vintage Art Deco silk scarves. And somehow, “the whole is so much more than the sum of its parts” says fashion expert Mark Butterfield of C20 Vintage Fashion.

In much the same way that Hendrix cherrypicked from rock, soul, blues and jazz in his music, his wardrobe also became a heady melting pot. Being a Black man in flower power made Jimi unique. “Hendrix’s Black cultural heritage made him comfortable in his stylistic expression with clothes. His Black stylin’ created a flamboyant and flash individual statement, often combining a unique selection of disparate stylistic elements” says Butterfield, who helped curate The Boutique in 1960s exhibition at the Fashion and Textiles Museum.

During his time in Britain, Hendrix also eased up on the chemical straightening and let his natural afro grow through. But while he may have escaped America’s overt social segregation, racism still reared its ugly head for Hendrix in Britain, as documented by a velvet jacket in the Handel & Hendrix London collection, with a distinctive tear. Davies from the museum, currently closed for refurbishment and reopening in May 2023, explains “the story is that someone punched Jimi at a gig and it was possibly racially aggravated. He tore his jacket on a nail on the floor”.

In 1967, just one short, sweet year since leaving America, Hendrix returned the reigning champion when he stole the show at the Monterey Pop Festival. His maximalist stage-wear included a hand painted jacket by designer Chris Jagger, Mick’s brother. “It’s early doors Jimi and he’s not going to turn up in H&M jogging pants is he?! There are feathers fucking everywhere. He just looks incredible!” reminisced broadcaster Shaun Keaveny on the Handel & Hendrix Unlocked podcast. “This is him presenting himself to the American audience, having broken Britain”

And unlike David Bowie, who later used Ziggy Stardust as his dazzling on-stage alter ego, for Hendrix it was always showtime. By 1968, here was little difference between Hendrix’s stage and personal clothing, even while relaxing at the Brook Street home that he shared with girlfriend Kathy Etchingham, which the nomadic performer considered his first taste of “a real home”.

Situated in a heart of Mayfair’s commercial district, Hendrix was finally free to jam at speaker-blowing volumes without disturbing the neighbours. The bright lights of Soho were within strolling distance, including The Scotch of St. James and Ronnie Scott’s music venues, record shops where he would pour over the latest releases, and clothing boutiques such as Kleptomania on Kingly Street, where Hendrix indulged his love of lace cuffed shirts.

Like a magpie, Hendrix’s home mixed sumptuous velvet curtains and a Persian rug from the nearby John Lewis department store, with antique treasures scored from Camden, Chelsea and Kensington markets. “Tellingly, there’s no dining table. This was the fashion with the young London set to lounge around on the floor or the bed” says Davies.

Hendrix’s final UK performance at the Isle of Wight Festival in August 1970, gave us one of his most iconic looks. Having spent the past few years flirting with British dandyism, Hendrix’s style metamorphosis came full circle, as he stepped out on stage wearing an outfit that told us exactly who Jimi Hendrix the American was. In celebration of his Cherokee bloodline, Hendrix donned a suede jacket fringed with tassels and beads, his natural afro hair framed by a fuchsia silk bandana to stop the sweat from dripping into his eyes. NME described Hendrix as “dressed in a multi-coloured outfit that must have been designed by a hallucinating tailor”, as his Star-Spangled Banner protest song, chastising the Vietnam War, rang out across the heads of the 700,000-strong audience.

Yet while Britain made Hendrix, it ultimately also helped destroy him. Fame came fast and furious here, and with it a predictable cast of challenges. But in the end, it wasn’t the trippy party drugs that killed him. Like his idol Elvis Presley, it was the far more mundane ‘mother’s little helpers’; the uppers and downers taken to keep pace with the relentless merry go round of work commitments – which for Hendrix could easily involve three energy-draining shows per night – that finally got their claws into him at the tender age of 27.

On the 18th September 1970, having spent the previous day browsing the latest styles on the King’s Road and Kensington Market, the dedicated follower of fashion was found dead from an apparent overdose of sleeping pills in the basement apartment of the Samarkand Hotel in Notting Hill. Flown back to the US for the funeral, Hendrix took his final bow in a flannel shirt, perhaps the ultimate indignity for a man famed for wearing a cloak of flamboyance.

But in the four short years between touching down in London and his untimely death, Hendrix still accomplished more than most can dream of in a lifetime, reinventing rock ‘n roll using a combination of fuzz, feedback and controlled distortion, while creating an instantly recognisable image that sang out to future generations of personal freedom.

So what would Hendrix make of turning 80 this year? Not much, according to rock music’s greatest showman. “I don’t think I’ll be around when I’m eighty. There’s other things to do besides sitting around waiting for eighty to come along, so I don’t think about it too much”. On that note, we salute you Jimi Hendrix.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News