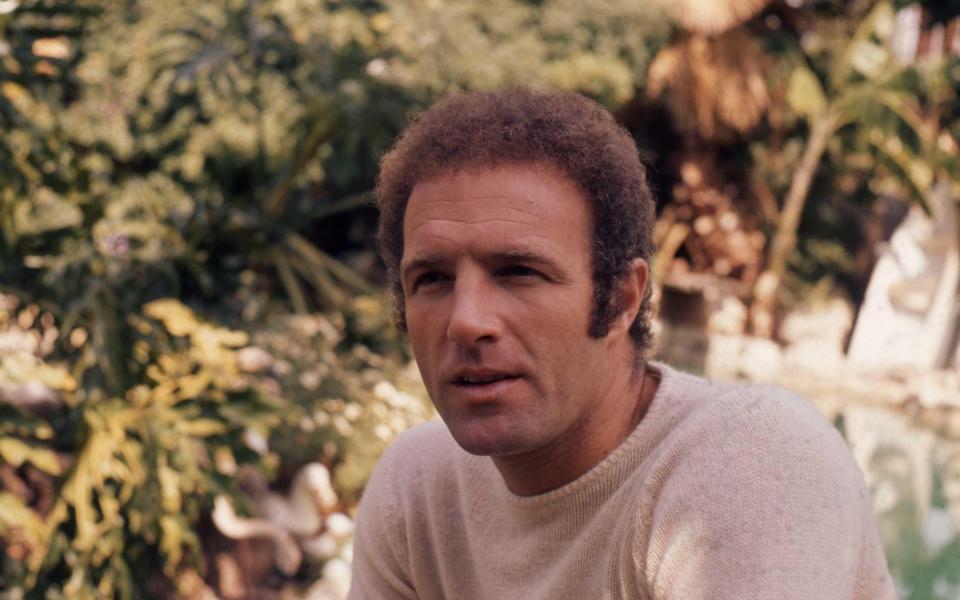

Coarse, sleazy, unreconstructed – we’ll never see another actor like James Caan

On the set of Howard Hawks’s 1966 western El Dorado, the story goes that John Wayne was playing chess between scenes. On the opposite side of the board was some 20-something nobody from television who’d starred in Hawks’s previous film: a car-racing thriller which had spluttered at the box office. Wayne, meanwhile, was still a Hollywood icon, riding high in the twilight of the studios’ glory years.

Perhaps to quietly maintain dominance, Wayne pointed to the horizon and asked this young upstart if he could see anything, then shifted a piece in his favour while his rival’s back was turned. Unfortunately, it wasn’t turned enough. The youngster spotted the sleight, leapt up in a fury and swung for the older star: the punch didn’t connect though; fortunately Robert Mitchum intervened.

Wayne was still the top dog, but within four years his career was all but finished – while the youngster was cast in a picture that would later be widely considered the greatest ever made, and was about to give one of the greatest performances in it. Cinema-goers were no longer interested in the 6’4” icon: they wanted the punk who swung the punch at him. And the particular punk who swung that particular punch was James Caan.

Caan, who died this week at the age of 82, wasn’t one of the early titans of method acting, like his contemporaries Dustin Hoffman, Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. But even so, the Jewish, Bronx-born butcher’s son brought a physical combustibility to his roles that seemed to flare up before your eyes, as if he was a fire that had broken out on set.

That greatest-ever film just around the bend in the late 1960s was, of course, The Godfather: Caan played Sonny Corleone, the hot-tempered heir apparent to the Corleone crime family enterprise.

Sonny’s famous death – an ambush at an airfield tollbooth – is volcanically excessive in its sheer brutality, and therefore entirely befitting of a man whose recklessness, short fuse and roaring libido doubled as gifts and tragic flaws. Caan played it all so convincingly that he quickly gained an off-screen reputation as one of Hollywood’s new breed of hard-brawling buccaneers.

In 1976, an interviewer from Playboy asked if he really was the same “macho pig” whose behaviour was regularly tutted about in magazines.

“Anybody says I am, I’ll kick the s___ out of him,” he replied.

But people continued to say that, and with good reason. Caan might have bridled at Playboy’s line of questioning, but he happily took up residence in the famous party mansion belonging to Hugh Hefner, the magazine’s founder, after the breakdown of his second marriage in the 1970s. There were arrests and lawsuits too – and, after the death of his sister in 1981, a spiralling cocaine habit which was partly responsible for his five-year absence from the business later that decade.

Coarse? Sleazy? Unreconstructed? Absolutely. Could an actor get away with it today? Almost certainly not. Yet like the eldest Corleone sibling, his weakness was also a strength: Caan’s glorious, undisguised flawed-ness was what made him so relentlessly gripping to watch.

His glut of tremendous roles in the 1970s – in films as varied as The Gambler, Rollerball, Cinderella Liberty, A Bridge Too Far, Funny Lady (opposite Barbra Streisand), the even-then scorchingly un-PC Freebie and the Bean – showed just how many uses an inventive film business could find for a fearless and indecently gifted young working-class star on the make.

But perhaps it wasn’t until he played the ace safe-cracker Frank in Michael Mann’s extraordinary 1981 crime thriller Thief that a film managed to distill Caan’s essence down to its maximum purity and potency – yes, the vigour, menace and coolness, but also a deep, quiet existential ache, and that steely blue-collar diligence that confers meaning on his characters’ travails.

After this career best performance, the untimely career break soon followed, and by the time Caan was ready to return to work, it was as if Hollywood had forgotten what to do with men like him. Yet when anyone remembered – Wes Anderson in Bottle Rocket, James Gray in The Yards – the results weren’t to be missed. And he saw the potential in a part many of his contemporaries turned down: Paul Sheldon, the romance novelist abducted by an obsessive fan, in Rob Reiner’s 1990 adaptation of Stephen King’s Misery. Even under hostage conditions, he held his audience captive.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News