Could M3GAN exist? The scientific truth about killer robots

The horror hit of the year so far is M3GAN, which was released in the US in the first week of January and has taken nearly $100 million at the box office. It tells the story of an orphaned girl, Cady, who is given an experimental robot called M3GAN to assist with parenting duties. M3GAN does her job, to a fault, becoming hostile to anything – and anyone – that threatens Cady. M3GAN, as befits a ruthless machine, is creative about her instruments of death. Nail guns, a paper guillotine, a screwdriver: she uses anything she can find. As AI apocalypses go, M3GAN is hardly Skynet from Terminator, but it is entertaining all the same.

M3GAN comes from a rich lineage, not all of it as schlocky as she is. The word “robot” dates back to a 1920s Czech film, but the idea of sentient machines, or automata, has been a feature of speculative fiction for much longer. More recently, the idea of a humanoid robot that gains sentience and turns on the people around it has become a staple of film and TV.

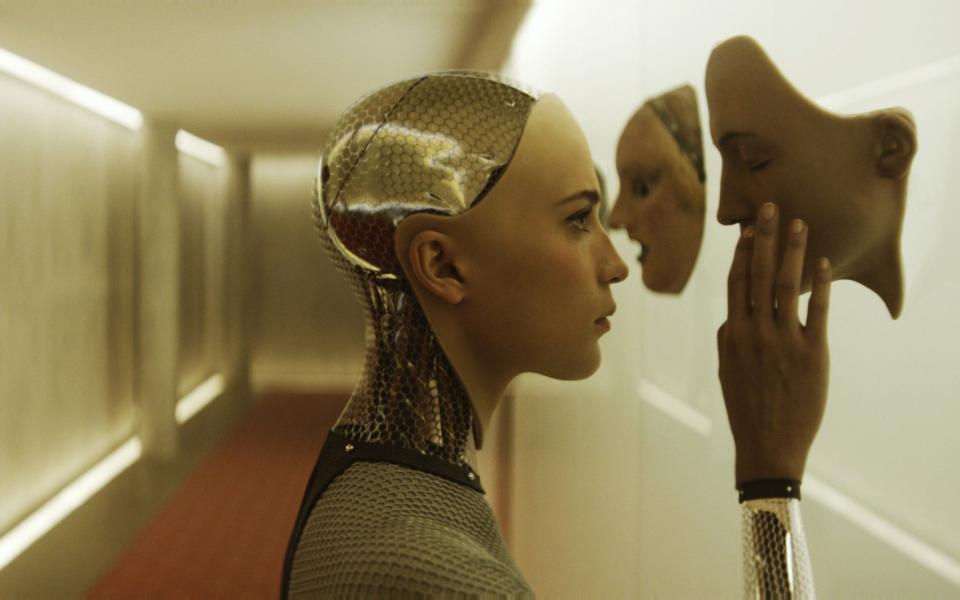

Think of I, Robot, where robots learn to violate strict laws governing their behaviour. Or Blade Runner, in which lifelike robot replicants must be hunted down. Or Ex Machina, Alex Garland’s film in which a beautiful android played by Alicia Vikander tricks her way out of captivity. In most cases, these characters are ways of representing what computer scientists have called the Singularity, the moment where an AI becomes uncontrollable and irreversible. In some films, like the Matrix, this is presented as a more nebulous concept, but Garland clearly felt this concept would be more compelling on screen if it looked like Alicia Vikander. There is something about the humanoid depiction of this technology that plays on our fears.

“It’s fascinating how anthropomorphic our thinking about robots is.” says Dr Dan Susskind, author of A World without Work and a professor of AI at Oxford. “A lot of it has to do with the fact that human beings have been the most capable machines around for some time. So we make ourselves the benchmark: how we look, think and reason. If a machine is to outperform us, the thinking goes, it has to look and act like us.”

The reality of humanoid robots seems to be some way off. Compared to what we have seen on screen, the real-life robots are often laughable. Take Ai-Da, billed as the “world’s first ultra-realistic artist robot” and named after Ada Lovelace, the pioneering computer scientist. A kind of souped-up shop mannequin in a wig, Ai-Da uses cameras and a robotic arm to paint pictures based on prompts she is given. She is wheeled out at various cultural events, like Ted talks and Glastonbury, and hailed as the future of art. Yet her paintings are terrible; the work of an accomplished toddler, at best.

Last year, AI-Da was called upon to give evidence to the House of Lords debate on AI. Sadly the machine, described in the Guardian as “a sex doll strapped to a pair of egg whisks” shut down before she got going. She is hardly the first person to nod off midway through a session in the House of Lords, but most of the others aren’t plugged into the mains.

Ai-Da is not representative of all robotic development. Every few months a scary video will go viral, displaying the physical capabilities of some ominous American company’s latest prototypes: the most recent from Boston Dynamics showed its robot, Atlas, backflipping. Drones have played a vital role in the war in Ukraine, while police drones are increasingly common around the world. Yet while there have been striking advances in drone technology, the results do not look like Harrison Ford in a trenchcoat.

“The media loves this idea of robots that are like humans, so we’re not sure if they’re humans or robots,” says Professor Helen Hastie, a professor of computer science and robotics at Heriot Watt University and Co-Lead for the National Robotarium. “But the reality is that it’s very, very difficult to build a general AI that can help with the laundry and talk about current affairs. People see AI in the media and think: ‘Oh my gosh it’s going to happen tomorrow.’ But we’re so far away from that.”

On the contrary, she says it is important for robots to look and feel appropriate to their function. “We make robots for monitoring offshore platforms: they are hard, rugged, yellow things,” she says. “If you put them in your home people would freak out. But if it’s going to be in your home, it should look like a robot. That will help with societal acceptance. Humanlike robots risk falling into the uncanny valley, where they become more unsettling the more lifelike they are.” M3GAN is a good example of this. “As soon as you get into the uncanny valley, you can put people off the robots themselves.”

Susskind points to Moravec’s Paradox, coined by the computer scientist Hans Moravec, which Susskind describes as “the surprising fact that many of the basic things we do with our hands are the most difficult tasks for a machine to do. It’s why we’re likely to see robot lawyers and accountants well before we see robot hairdressers and gardeners.” He says this is part of the reason that ChatGPT, the AI-powered text function, built by the California firm OpenAI and released last year, has caused such a stir.

“The latest machines do not think or reason like humans,” he says. “It’s why many experts have been caught flat-footed in thinking about the capabilities of AI. What we find difficult to do is not what machines find difficult to do, because they operate in fundamentally different ways to us.” AI that generates text and pictures can do things that previously we’d have thought were impossible for machines, like write credible essays and poetry.

For years, AI software has been used to write sports and business reporting, where a set of numbers needs to be turned into more-or-less predictable prose. Bloomberg, for instance, explains that machine learning helps it give its customers what they need as quickly as possible.

This trend will only accelerate. As Susskind points out, this is the worst this software will ever be. ChatGPT is a version of the third generation of GPT software: GPT-4 is expected to be released later this year, and will be another step change. It seems inevitable that white collar jobs, in professions like law, accounting and journalism, will be replaced before lower status but more physically demanding roles like deadheading roses.

Having conquered chess and Go many years ago, robot game-players are making inroads into other, more challenging games. Most recently, at Meta, an AI called Cicero beat human players at online game Diplomacy. It’s a striking achievement because Diplomacy, unlike those other games, requires players to make agreements and then renege on them. Meta’s robot was forging pacts with human players and then betraying them. None of the human players suspected they were against a bot. The machines have always been good at maths; now they’re good at lying, too. But these machines are not embodied: they exist in browser windows and chat functions, not a more-or-less convincing doll.

For all the apocalyptic language around this subject, Hastie says she remains optimistic about robots’ potential. “AI and robotics will change the job landscape, but they will create jobs, too,” she says. “Forty years ago we didn’t know what a web developer was, and now there’s lots of web developers. We believe there will be new jobs, and they’ll be fulfilling jobs. And people will have more time for leisurely activities.”

Activities like… watching horror films about robots. While murderous humanlike dolls of the sort featured in M3GAN remain firmly fictional, other kinds of AI are surprisingly advanced. The robots are coming, but not in the way the films predicted. They will not throw you from office windows or stab you while you sleep, but they might quietly replace your job in insurance.

Ai-Da might not be creating great works of art, but many companies are already turning to AI-generated images and text instead of hiring copywriters or artists. The revolution sounds so boring that it is happening without us noticing, and there's not a mannequin in a wig in sight.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News