The day Dylan went electric: ‘They certainly booed, I’ll tell you that’

The poet in black struck an angry chord and told his people how it feels. “I got a head full of ideas that are drivin’ me insane,” Bob Dylan barked over a skiffle rock clatter called “Maggie’s Farm”, a servant-class metaphor for breaking free of the oppressive, conformist shackles of 1960s America. The song ended in a flurry of bluesy discord, and a roar went up unlike any heard in popular music before. Half shock and excitement, half dissent and betrayal, a torrid clash of howls and boos. At the side of the stage, organiser Pete Seeger reportedly demanded an axe to cut the microphone cord.

Fifty-five years ago today, the traditionalists of 1965’s Newport Folk Festival, Rhode Island, had watched Dylan walk onstage with an unannounced band, plug in a guitar and play his first ever electric set. An act that kicked open the door for generations of musicians, from The Beatles to Radiohead, to plot their own creative paths on their own terms, to challenge their audiences with the sounds of the future rather than pander politely to established tastes. But the historic spark of the moment had, in the words of radio broadcaster John Gilliland, “electrified one half of his audience, and electrocuted the other”.

It’s easy in retrospect to consider the Newport naysayers as mere folkie Luddites, distraught at the piercing spears of mainstream rock’n’roll breaching their precious, authentic bubble. But there was more at stake. America in 1965 was a demoralised country, its hopeful new political dawn gunned down in Dealey Plaza, Dr King’s dream bloodied by the police brutality against civil rights protesters on Alabama’s Edmund Pettus Bridge and the Vietnam War rolling on towards an increasingly hollow and unattainable “victory”.

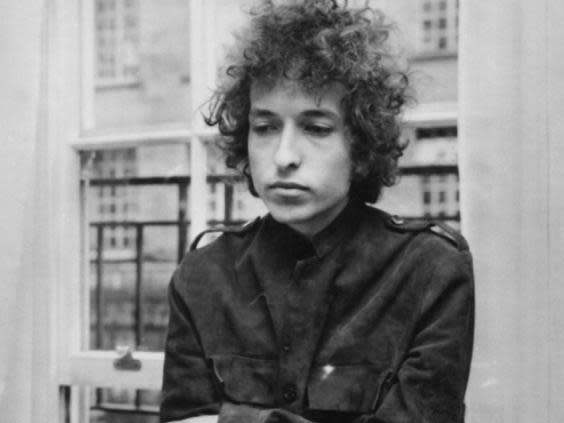

Over the course of his first four acoustic-and-harmonica folk albums, Dylan’s incisive, poetic and charismatic rebel songs had made him the primary voice of youth protest culture. At the 1963 Newport festival he’d gained godhead status with a defiant rendition of “Blowin’ In The Wind” accompanied by Peter, Paul And Mary, Joan Baez and The Freedom Singers.

So when, just two traumatic years later, Dylan plugged in for three songs – “Maggie’s Farm”, his recent single release “Like a Rolling Stone” and “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” – on the very same stage, he was hectored from all sides of folk philosophy. The purists objected to his betrayal of their righteous and historic music: it was, critic Greil Marcus would say, “as if something precious and delicate was being dashed to the ground and stomped”. The counter-culture progressives, meanwhile, objected to Dylan turning his back on the cause. Over the coming year he’d play to increasingly angry and hostile audiences, heckling, booing and storming out of his shows across the globe. He’d become, in some eyes, the “Judas!” of protest folk.

“A lot of people coming to Newport were very upset about the world in general,” blues folk singer Elijah Wald told author Spencer Leigh for a new Dylan biography Outlaw Blues. “The weekend that Dylan went electric is the weekend that Lyndon Johnson doubled the military draft and firmly committed the US to the war in Vietnam. Many festivalgoers hoped that Dylan and the other artists would do what they did in 1963. Everybody would join arms and the crowd would sing ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ and ‘We Shall Overcome’ and it would make them feel that they were not alone and were part of something that was going to change the world.”

For Dylan, though, going electric was part of a grand tradition of confrontational artistic progress. In 20th-century music, to that point, precedents for artists refusing to give their audiences what they wanted were rare indeed. Jazz maestros like Thelonious Monk might cut shows short if they weren’t feeling inspired, but all of the much-vaunted rebel antics of rock’n’roll, from Jerry Lee Lewis’s burning pianos to Keith Moon’s exploding drumkits, were in the name of crowd-pleasing entertainment. In art and literature, however, the great artists – Picasso, Joyce, Eliot, Orwell, Lawrence, Beckett – rarely pandered, and that’s where Dylan’s aspirations lay. He was embedded in the more provocative forms of Fifties and Sixties culture, a sometime visitor to Warhol’s Factory and an admirer of the Beat writers; Howl author Allen Ginsberg was a close friend and Dylan loved how Burroughs had shuffled the pages of Naked Lunch before publication.

“The stuff that trained me to do what I do was all individually based,” he’d tell Rolling Stone in 2006, citing Slim Harpo, Patsy Cline, Socrates and Walt Whitman, “the individual crying in the wilderness … artists with the willpower not to conform to anybody’s reality but their own.”

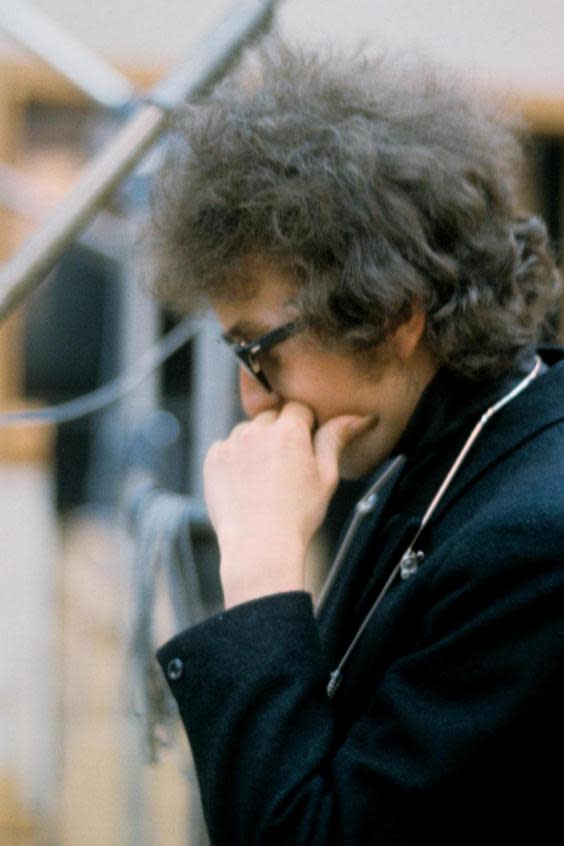

Inspired by meeting The Beatles in 1964, the success of The Byrds’ brand of airy electric folk and the electric blues projects of his friend John P Hammond, Dylan had embraced electric music months before Newport. In January 1965 he’d recorded his fifth album Bringing It All Back Home, the first side of which was recorded with a full electric band and largely eschewed protest messages, at surface level at least, in favour of Beat-inspired surrealist lyrics. The album gave him his first US Top 40 hit with stream-of-consciousness rocker “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, but when he returned from a subsequent solo tour, having spent time hanging out with The Beatles, The Stones and Donovan in London, he was so tired of his acoustic material he considered quitting music. “I was very drained,” he told Playboy in 1966, “the way things were going, it was a very draggy situation.”

He was revitalised by writing what he described as a 20-page “piece of vomit” which he condensed into his monumentally acclaimed breakthrough single “Like a Rolling Stone” which, at six-minutes long, was itself a challenge to pop orthodoxy and a bold, brilliant statement of creative autonomy. He arrived at the Newport Folk Festival, four days after its release, mid-transformation; within days the single would reach No 2 in the US, turning Dylan from folk hero to rock star, but as far as the less hip quarters of Newport were concerned he was still their freewheelin’ folk figurehead.

On Saturday 24 July, Dylan performed a short acoustic set and was rapturously received. He’d intended to play solo again for his second billed slot the following day, but was riled by compere Alan Lomax’s disparaging introduction for one of the weekend’s electric acts, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. “F*** them if they think they can keep electricity out of here,” he reportedly snapped, “I’ll do it.” Swiftly pulling together a band made up of Butterfield players and on-hand additional musicians, Dylan rehearsed that night at a mansion being used by a festival organiser and hit the stage with a full electric band. It was undoubtedly, at that point, the highest-profile example of real rock’n’roll rebellion in history – from a folk guy.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen, but they certainly booed, I’ll tell you that,” Dylan said at a press conference in San Francisco five months later. “You could hear it all over the place … I mean, they must be pretty rich, to be able to go someplace and boo. I couldn’t afford it if I was in their shoes.”

Al Kooper, who played the Hammond organ riffs on “Like a Rolling Stone” and performed with Dylan at Newport, would claim the crowd were upset because of the brevity of the set (unlikely, since they booed the very first number), and others would claim the sound, pumping electric music through a rudimentary folk festival PA, was so poor that the audience turned sour. This was certainly the origin of the Pete Seeger axe story; “Get that distortion out of his voice,” he’s reported to have said, “it’s terrible. If I had an axe, I’d chop the microphone cable right now.”

“There had never been a rock festival at that point,” Wald told Leigh for Outlaw Blues. “Nobody had ever had the experience of sitting in a field with 18,000 people and having a full-scale rock band blasted at them. Some loved what they were hearing … some people were horrified because they were so loud.”

When that night’s compere Peter Yarrow enticed Dylan back on stage for a solo acoustic encore of “Mr Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”, a glimpse of a Dylan fast evaporating, the crowd were instantly won over. But as Leigh suggests, “Dylan rather liked people shouting at him. After he’d done Newport he thought ‘this is the way to go.’”

He planned a supporting tour almost designed to antagonise the staid element of his audience. He’d play a short opening acoustic segment, then return with a full band (which would eventually become known as The Band) for an electric set intended to shock and provoke, instructing his musicians to keep playing no matter how adverse the reaction. In that sense it was a huge success. At his first show after Newport, in Forest Hills, The New York Times reported “the young audience’s displeasure was manifested at the end of most of the numbers, by booing and shouts of ‘we want the old Dylan’. The young star plowed valiantly on, with the sort of coolness he has rarely displayed on stage.”

“The booing was much louder,” Wald told Leigh, “and he seemed to be totally enjoying it.” “Dylan met with such antagonism when he went electric and he just f***ing went for it,” added film director Todd Haynes. “He used that energy to fuel him further, crank up the music louder and basically invite violent dissent. That is punk rock in 1966, before anybody did that.”

Liberal US coastal cities and university halls received Dylan positively, but elsewhere word had circulated that booing the second half was de rigueur. “Every night was like going for broke, like the end of the world,” Dylan said in 1987; “We had to tell ourselves they were wrong and we were right,” said The Band guitarist Robbie Robertson. The booing became too much for drummer Levon Helm, who left the tour in November 1965, but Dylan seemed to revel in the enmity. Dylan expert Derek Barker told Leigh: “Dylan did get off on alienating audiences. [Helm’s replacement] Mickey Jones said that Bob was never more animated or excited as when he put on an electric guitar.”

His antagonism extended to press engagements. “I think of myself as a song and dance man,” he told a California press pack, and teased the Australian press at Sydney airport by claiming the band were “friends of my grandmother”. For a Paris press conference, he brought along a puppet called Finian to answer questions for him. “Are you certain of anything?” one reporter asked, to which the puppet replied, “Yes, ashes, doorknobs and windowpanes.”

By the time the tour reached the UK and Ireland in May 1966, Dylan seemed in open warfare with parts of his fanbase. When someone at the Dublin Adelphi yelled out “leave it to The Rolling Stones!” he responded – according to the watching Bob Geldof – by announcing every song as “Mr Tambourine Man” but never playing it. In Edinburgh, the local Communist Party bought tickets in order to barrack him, and folk diehards brought along their own harmonicas to try to drown out the band.

Leigh himself saw Dylan in Liverpool. “The really committed folkies were throwing down their programmes and walking out shouting comments at the stage,” he says. “I remember him saying to someone ‘there’s a guy there looking for the saviour, well there’s a picture of Jesus backstage.’ He came out with some classic lines … these people thought that Bob Dylan was the new messiah, telling us how to look at world events today. People felt very let down when he started to write personal songs.” Outlaw Blues quotes one regretful fan: “Dylan was the voice of rebellion and protest and I didn’t want him as just another rock star.”

Three days later at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, the hostility reached its historic peak when a fan shouted “Judas!” from the dark. “I don’t believe you… you’re a liar,” Dylan replied and told his band to play “Like A Rolling Stone” “f***ing loud”. Several attendees lay claim to the cat-call: one John Cordwell claims he was complaining about the poor sound, while Keele student Keith Butler was filmed leaving the venue ranting “Any pop group could produce better rubbish than that! It was a bloody disgrace! He’s a traitor!” “I kind of think: ‘You silly young bugger,’” Butler reminisced in 1999.

“Judas, the most hated name in human history!” Dylan said in 2012. “If you think you’ve been called a bad name, try to work your way out from under that. And for what? For playing an electric guitar? As if that is in some kind of way equatable to betraying our Lord and delivering him up to be crucified. All those evil motherf***ers can rot in hell.”

Which was clearly how Dylan felt in 1966 too. Before leaving the stage at the last show on the UK tour, at London’s Royal Albert Hall, he informed the depleted audience that they didn’t know how to appreciate him or his music, and that he’d never return. It would prove a prophetic statement – on 29 July, a month after the release of his legendary double album Blonde on Blonde, Dylan was reportedly involved in a somewhat mysterious motorcycle accident and wouldn’t play a major tour again until 1974.

Noting the many walkouts, The Times printed a review from the London show including the now legendary line “now we know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall”. But that wasn’t the only element of the evening to resonate through the ages. All four Beatles themselves were at the concert, baffled at the reaction but inspired by Dylan’s steadfast dedication to his art and unwillingness to bend to the demands of his audience. Having already taken Dylan’s cue on “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” and the folk-inflected Rubber Soul album, within a few months they’d shock their own fans to attention with the psychedelic loops of “Tomorrow Never Knows” on Revolver and decide to stop touring for good.

Over time, Dylan going electric would come to represent a shift in attitude in early rock music, where the important artists assume full control over their output and performances, free to experiment rather than cater to their audiences. Psychedelia exploded with records out to challenge what music could be. Brian Wilson dedicated his life to chasing his immaculate post-pop visions around his studio sandpit. The Velvet Underground played chiming drones in art galleries and Pink Floyd sent arts clubs on hypnotic sonic trips, spawning a new underground culture. David Bowie invented alien superstars and then killed them off at their peak. Rock’n’roll became a true off-road adventure, with the fans no longer giving directions but biting their nails in the passenger seat.

Today, when My Bloody Valentine or Sunn O))) submit their audiences to deafening hell-chords, when Arctic Monkeys relocate to the Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino or when Björk performs entire sets of futuristic flotation tank music dressed as a Martian chrysanthemum, it’s all made possible by Dylan ripping up Newport’s rule book. Thanks to him, as he raged in “Maggie’s Farm” that fateful day, only the crummiest acts still “sing while they slave”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News