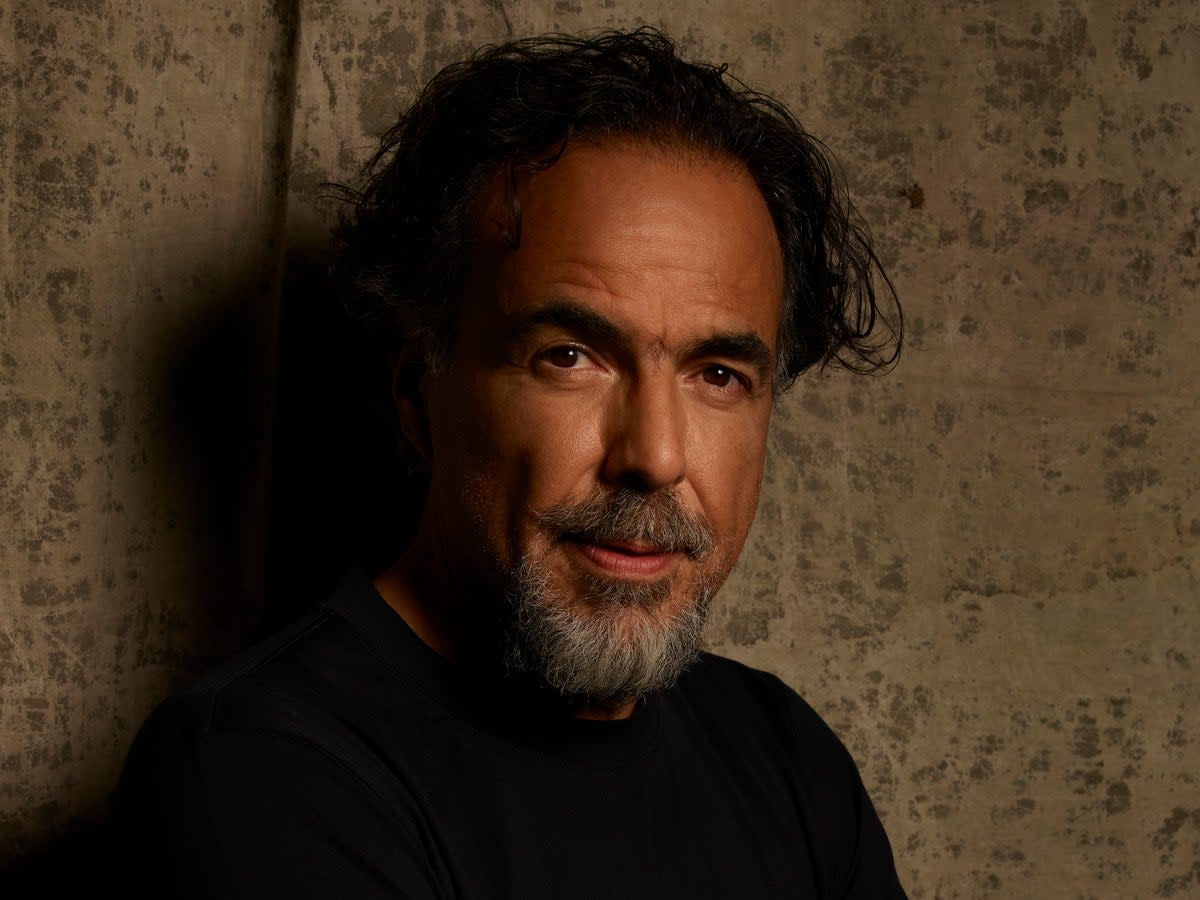

‘No award will solve your deep needs’: Alejandro G Iñárritu on Bardo, being his own worst critic, and those Robert Downey Jr comments

Nine years ago, the director Alejandro González Iñárritu spent eight months in the Canadian wilderness with Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom Hardy. It was minus 40 degrees, the sort of cold that cuts to the bone; the sort of cold that makes it hard to open your eyes, as DiCaprio once described it. The Revenant, for which Iñárritu recieved one of the five Oscars to his name, is regularly mentioned in the same breath as Apocalypse Now when discussing the Toughest Film Shoots Ever. Compared to Bardo, False Chronicles of a Handful of Truths, Iñárritu’s latest film, it was a walk in the park.

What could be harder to make than The Revenant, a film that saw its star chow down on raw bison liver and multiple crew members exit due to conditions one source described as a “living hell”? “Bardo was 100 times tougher,” says Iñárritu over Zoom from his cosily lit home office in Los Angeles. In this sprawling and surreal drama, Daniel Gimenez Cacho stars as Silverio Gama, a journalist, documentarian and clear stand-in for Iñárritu. They have the same great, grey beard. When he and his family visit their native Mexico City on holiday, Silverio is sucked into a waking dream replete with reveries on identity, history and his looming mortality. (In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is the liminal state between death and rebirth.) “This demanded more from me than any other film,” says Iñárritu. Never mind mountains or forests; Bardo takes place in the most treacherous place of all: “It’s the personal geography of my existence.”

Bardo was a hard sell. “Nobody wanted to do it,” says the 59-year-old. So he took a leap and self-financed the film in its early stages. It was later picked up by Netflix. “People were afraid,” he explains. “This is not a conventional film. It’s a personal film; it’s in Spanish; I didn’t have any huge world stars; I didn’t want anybody to read the script.” But their concerns never dampened his desire to make Bardo. Rather, they cultivated it. “I have this kind of disease where the more people challenge me on something, the more I put store in it. When people say, ‘Yes, that’s great’ and it’s greenlit, that triggers my suspicion. You know, maybe then my idea is not original.” Finding financing for Birdman, his hallucinatory 2015 showbiz satire, starring Michael Keaton as a washed-up actor mounting a comeback on Broadway, was a similar struggle. It won four Oscars.

If you have seen just one Iñárritu film in the past 20 years – Amores perros (2000), 21 Grams (2003), Babel (2006) – you will know him to experiment with form. Bardo is no different. Only this time, coupled with an unmistakable personal bent and a lengthy runtime (two hours, 39 minutes), his playfulness has attracted eye-rolling. “Self-indulgent” is a dig being bandied about among critics. It’s also a word that appears in Bardo itself when Silverio runs into Luis, a former friend and fellow journalist (played by Francisco Rubio) who rails into Silverio’s latest “narcissistic” work, dismissing it as a “pretentious” mishmash of “pointless scenes” that “lacks poetic inspiration”. Sounds familiar.

Iñárritu typically recoils from reading reviews, good or bad. “I try to navigate it with a lot of respect and any opinion is super OK but I don’t have any purpose for reading it,” he says, explaining that no criticism will change the film. “Artists, we can be very tough on ourselves. I think I have enough with one critic as myself.” He has, however, evidently seen the criticism of Bardo. His reaction? To laugh. “It’s obviously a meta moment,” he says. “There is no harsher critic than myself so I know how predictable the mind is and what can be said about the film. All of the things [Luis] says are things I could see myself and others thinking so when it happened in reality, it made me laugh because it reaffirmed what the film was saying.” He pauses for a moment. “I am sorry that some journalists took it so personally and I would say that scene was unfairly misinterpreted.” The scene is about artistic opinion, Iñárritu says, but it’s also about truth. “Their debate is about the world we are living in. It’s binary; we reduce everything to one side or the other and there is an incapacity to see range,” he says. “As a person, I am very much in that moment in my life, [realising] that we cannot pretend any point of view is the truth.”

Iñárritu is well-acquainted with criticism, the way any much-acclaimed industry giant is. And in the past, he has been known to bare teeth of his own. In 2015, he launched into a diatribe against superhero films. “Cultural genocide” is how he described the genre. When an interviewer quoted his remark to Robert Downey Jr, the Iron Man star mocked Iñárritu’s Mexican roots: “Look, I respect the heck out of him, and I think for a man whose native tongue is Spanish to be able to put together a phrase like ‘cultural genocide’ just speaks to how bright he is.” The actor’s response was widely criticised; his publicist later said it was meant to be “complementary”. Seven years on and Iñárritu is little fussed about it. Has Downey Jr reached out to apologise? “Of course not. Of course not. I don’t expect that,” he chuckles. “I honestly could not care at all. I am completely against what he said but I will defend his right to say whatever he wants. Anything he wants to say is fine, but for me it reads completely the wrong way.” Today, Iñárritu is more bereft than biting about the current film landscape. “Everything is becoming similar. There is more safety in IPs, remakes, things that already have value in popular culture. Original material is more suspicious every time – no matter how many awards you have.”

In person, Iñárritu carries himself with the casual intelligence and enthusiasm of your favourite professor. Chunky black spectacles and mad scientist hair help. Iñárritu also loves a simile. Over the course of our conversation, he compares certain situations to embracing an old friend, feeding an insatiable ghost, a turtle talking to a fish, the taste of mango.

Iñàrritu has previously said he came to directing “very late”. He was 35 when he made his debut film. By then, he had spent hundreds of hours behind a camera shooting commercials for a TV station. Prior to that he started off as a radio host. Bardo is a homecoming of sorts for Iñárritu. It is the first time he has shot a film in Mexico City in over two decades. After his 2000 debut Amores perros, he and his family moved to Los Angeles for his career, just as Silverio does in Bardo. The identity crisis that Silverio encounters is not unlike Iñárritu’s own. “That feeling of being out of place is the elusive material of Bardo,” he says.“It is difficult for the ones who have not lived through that to understand what I mean.”

For Iñárritu, that feeling came on like humidity. “It’s not like someone threw a bucket of water over me and I was wet suddenly.” Instead, he compares it to being in a muggy room. “You don’t realise what’s happening until everything feels very humid.” In the 21 years he has lived in the US, “little by little, those memories and affectations [of Mexico] have been eroding, and you start to feel as though you are not from any place”. One scene in the film illustrates it well. Silverio and his family are at LAX returning home from Mexico. A border force officer interjects: “This is not your home,” and argues that their permanent residence visas do not give them the right to call America home. The scene is practically a word-for-word re-enactment of something that happened to his wife three years ago. “Maria came to me crying and told me the story,” Iñárritu recalls. It’s strange, he says, “how your identity can basically be flipped just by a piece of paper being wrongly interpreted by someone”.

In 2016, Iñárritu entered a rarefied stratum. With Birdman and The Revenant, he became the third ever filmmaker to win back-to-back Oscars for best director – joining John Ford and Joseph L Mankiewicz. Each one of Iñárritu’s six films has been nominated for at least one Academy Award. They share a total of 45 nods between them. Last month, Bardo made the shortlist for Best International Feature Film. Iñárritu acknowledges that being recognised by your peers is a “beautiful” thing and that winning an Academy Award is “obviously fantastic” in the way it can help change a career. These days, however, he is after something less tangible. It’s that moment, he says, “when the audience is so touched by a film about something so personal to me and we connect through that. It’s indescribable, that feeling of not being alone, to be comprehended and to be understood”.

At this moment in my life, real success is basically to not want success

Twenty very successful years in the industry have taught Iñárritu a lot about being very successful. Namely, it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. “I can tell you there is no piece of metal or award that will solve what’s important, your deep intimate needs.” Finding success is to realise that success itself is a mirage, he says. It’s a tough lesson to learn but one he has taken to heart. “At this moment in my life, real success is basically to not want success.” He laughs, “I am not chasing the mirage anymore. It doesn’t mean I’ve solved anything. I am still the same idiot! Please don’t consider me as a guy with wisdom. I’m not wise, I am just a little more conscious that success won’t make my problems disappear.”

He gives a cheeky, knowing grin. “I know you’re going to write, ‘This motherf***er, of course he can say all that having won five Oscars.’ But I think every human being reading this will understand what I’m saying. Whatever success we’ve achieved, it is proven that it has not changed a thing when it comes to the really important things. Your anxieties, your insecurities; they will never be solved by exterior success.” Well, of course, this guy can say that. He’s won five Oscars.

‘Bardo, False Chronicle Of A Handful Of Truths’ is in select UK cinemas and on Netflix now

Yahoo News

Yahoo News