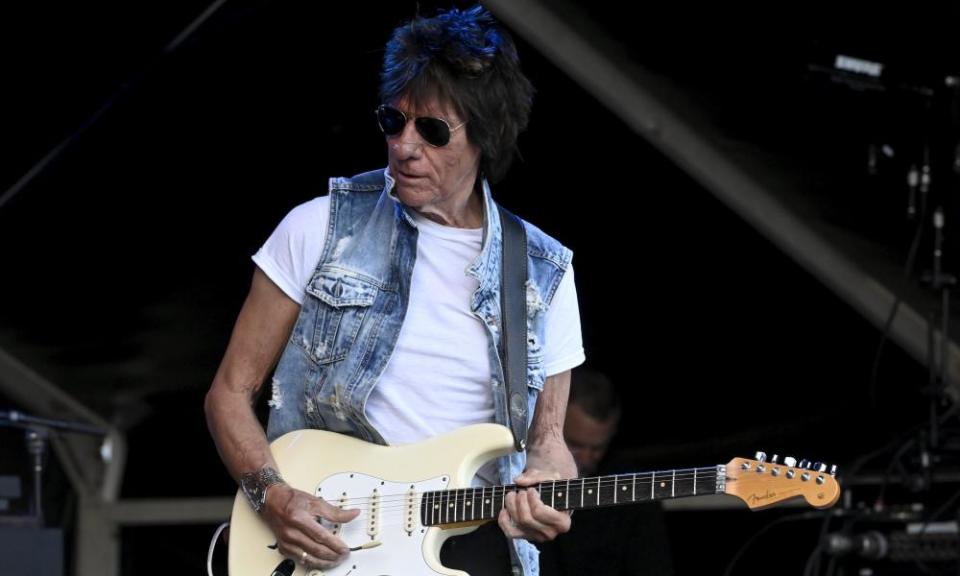

Heart full of soul: the maverick genius of Jeff Beck, the ‘guitarist’s guitarist’

Of all the career opportunities that could present themselves to an up-and-coming guitarist in the mid-60s, the offer of replacing Eric Clapton in the Yardbirds was one you might think twice about accepting. It wasn’t just that Clapton was talented; it was that – uniquely for British rock at the time – he was the Yardbirds’ star attraction. His presence so obviously overshadowed that of their frontman, Keith Relf, that one of their peers wrote a song about it. Manfred Mann’s The One in the Middle affectionately mocked Relf as “just a pretty face”. (Curiously, Relf could never be talked into performing it.) Trying to replace Clapton, you might assume, was a hiding to nowhere: anyone who tried was being set up to fail.

But Jeff Beck, who had been recommended for the job by his friend Jimmy Page, didn’t just replace Clapton. He transformed the Yardbirds, from blues purists struggling to square their love of Buddy Guy and Freddie King with the necessity of having pop hits (Clapton had walked out in protest at the band recording and releasing Graham Gouldman’s For Your Love as a single) to a band at the vanguard of British pop’s relentless forward progress. The first single he recorded with them, Heart Full of Soul, was another Gouldman confection, enlivened by Beck mimicking the sound of sitar – some months before the Beatles first deployed the instrument on Norwegian Wood – with a guitar played through a distortion pedal called a Tone Bender.

There was a hint of Who-ish feedback about his aggressive playing on its follow-up, Evil Hearted You: if you flipped the single over, you were confronted with the droning Still I’m Sad, with its Gregorian chant-inspired vocals, a signpost en route to the experimentation of psychedelia. By the time of February 1966’s Shapes of Things – howling feedback, a guitar solo audibly influenced by Indian raga, or, as Beck put it, “some weird mist coming from the east out of [my] amp” – the Yardbirds sounded like a completely different band from the one who had powered their way through covers of Smokestack Lightning and Good Morning Little Schoolgirl on 1964’s Five Live Yardbirds.

Beck could play the blues if he wanted to – listen to his slide playing on Heart Full of Soul’s B-side, Steeled Blues – but he was no one’s idea of a respectful purist. Tellingly, the song that had first piqued his interest in playing guitar was Les Paul and Mary Ford’s groundbreaking 1951 hit How High the Moon, a single that was as much about Paul’s electronic manipulation of sound through multitracking as it was about his guitar playing. When Beck’s mother dismissed it as “all tricks”, it only served to fire his enthusiasm further.

Throughout his tenure with the Yardbirds, Beck seemed as interested in the sonic possibilities of new technology as he did in demonstrating his instrumental prowess, “making all the weirdest noise I could”. The result was a succession of tracks that propelled the Yardbirds to the forefront of pop’s avant garde: Over Under Sideways Down, Lost Woman, Hot House of Omagararshid, He’s Always There. When Jimmy Page joined, briefly creating a lineup with two lead guitarists, their sound got more extreme still. The single that coupled Happenings Ten Years Time Ago and Psycho Daisies was impossibly potent and sinister, so far-out even by the standards of 1966 that it succeeded in alienating their fans – it barely scraped the charts in the UK – and the critics, one of whom derided it as an “excuse for music”.

Not long after its release, Beck acrimoniously departed the Yardbirds. “They kicked me out … fuck them,” he waspishly noted during the band’s 1992 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Producer Mickie Most attempted to fashion him into a pop star, a role to which Beck was entirely ill-suited, although the union produced the hit single and wedding disco perennial Hi Ho Silver Lining. His real future, however, lay on its B-side, an instrumental called Beck’s Bolero that he had recorded with Page, bassist John Paul Jones and the Who’s Keith Moon back in May 1966. It was epic, heavy and quite astonishingly prescient, pointing towards the direction rock would follow in the post-psychedelic era a year before the Summer of Love.

It still sounded ahead of the curve when it turned up on Beck’s solo album Truth two years later. By then, Beck had recruited singer Rod Stewart: with his bluesy vocals playing off Beck’s incendiary distorted guitar, Truth’s eclectic set of material – a reworking of Shapes of Things, plus versions of Greensleeves, Ol’ Man River and Willie Dixon’s I Ain’t Superstitous – presaged the sound of Led Zeppelin, the band Jimmy Page formed from the wreckage of the now defunct Yardbirds. Truth beat Led Zeppelin’s eponymous debut into the shops by six months.

Perhaps the Jeff Beck Group, which Truth’s follow-up, Beck-Ola, was billed under, could have followed Zeppelin’s path to superstardom. But there were problems, not least with maintaining a steady lineup. Stewart departed after Beck-Ola – an attempt to replace him with the then-unknown Elton John only got as far the rehearsal studio – taking bassist Ronnie Wood with him to form the Faces. Pianist Nicky Hopkins left, too: drummers came and went.

The fact that Beck couldn’t keep still musically may also have hindered their commercial progress. Beck-Ola was very much in the “heavy” style of Truth – Spanish Boots is particularly fantastic – but subsequent releases dabbled in funk, jazz and soul. Both 1971’s Rough and Ready and 1972’s Jeff Beck Group have their moments – I’ve Been Used and Jody on the former, Ice Cream Cakes and Going Down on the latter – but the NME critic who noted that the band’s musical skill frequently “far exceeds that of the material” had a point. In addition, it was hard not to be struck by the sense that Beck wasn’t that bothered about being famous, hence Beck-Ola’s self-deprecating sleeve note: “It’s almost impossible to come up with anything totally original – so we haven’t.”

By 1973, Beck had formed a new band with bassist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice. They might have had a hit single with Superstition, a song Stevie Wonder had given to Beck in return for performing on Talking Book – you can hear his beautifully delicate and sympathetic playing on its penultimate track, Lookin’ for Another Pure Love – had Wonder not changed his mind and released it as a single himself, complete with the iconic opening drum beat that Beck had come up with. The pair worked together again on Beck’s largely instrumental 1975 solo album Blow by Blow, on which the guitarist changed course again, this time to dextrous jazz-rock fusion. Its successor, Wired, featured a version of Charles Mingus’s Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.

By now, no one could predict where Beck was going to head next. Flash, from 1985, was a pop album produced by Nile Rodgers, albeit a pop album decorated with guitar solos that sounded close to contemporary heavy metal. (Beck subsequently professed to hate it.) Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop (1989) was an instrumental blues-rock album. Crazy Legs (1993) was entirely comprised of Gene Vincent covers. Who Else! (1999) bore the influence of ambient electronica and techno: THX138 and Psycho Sam sounded, unbelievably, not unlike the Chemical Brothers or the Prodigy. He collaborated with Guns N’ Roses, Kate Bush, Roger Waters, Hans Zimmer and Jon Bon Jovi. It was all evidence of a disinclination to be pigeonholed: the only thing you could rely on was that whatever direction his music took, his guitar playing would be incredible.

It was the kind of career that baffled the general public – of his latterday albums, only the relatively straightforward Emotion & Commotion, which saw him working with Joss Stone and Imelda May, was really a hit – and obscure quite how innovative Beck had been in the 60s. But it won him the undying admiration of his fellow musicians: the phrase “guitarist’s guitarist” might have been invented for him. His influence spanned generations. Brian May, David Gilmour, Slash and The Edge all attested to being inspired by Beck. Metallica’s Kirk Hammett claimed he learned guitar by playing along to the Jeff Beck Group’s Let Me Love You. The Red Hot Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante recalled listening to Truth as a kid and marvelling at Beck “pulling all these sounds out of the guitar … I didn’t know where they were coming from”. Even Eric Clapton, whose departure from the Yardbirds had kickstarted Beck’s career, marvelled at his replacement, “the most unique guitarist, and the most devoted”.

His last project was an album he released with Johnny Depp, a move that catapulted him into the news: 18 appeared in the wake of Depp’s defamation case against his former wife, Amber Heard. The controversy overshadowed the album’s contents, which were as unpredictable as ever. Trying to explain its tracklisting – on which a cover of the Velvet Underground’s Venus in Furs lurked alongside versions of the Beach Boys’ Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder), Killing Joke’s Death and Resurrection Show and Smokey Robinson’s Ooo Baby Baby – Jeff Beck came up with a line that neatly summed up his entire career. “Interesting things happen,” he said, “when you’re open to trying something different.”

• This article was amended on 12 January 2023. A previous version misnamed the Tone Bender distortion pedal as the “Toneblender”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News