‘This isn’t a clickbait story of a white family with a black kid’: Jimmy Akingbola on growing up in foster care

It is a typically sunny Los Angeles morning, with light cutting through the blinds, when Jimmy Akingbola greets me on a video call from his home. He is warm and bright-eyed, despite a gruelling night shoot that wrapped only hours before. Akingbola may not be a household name, but his face and quietly determined acting roles will be familiar to most British viewers.

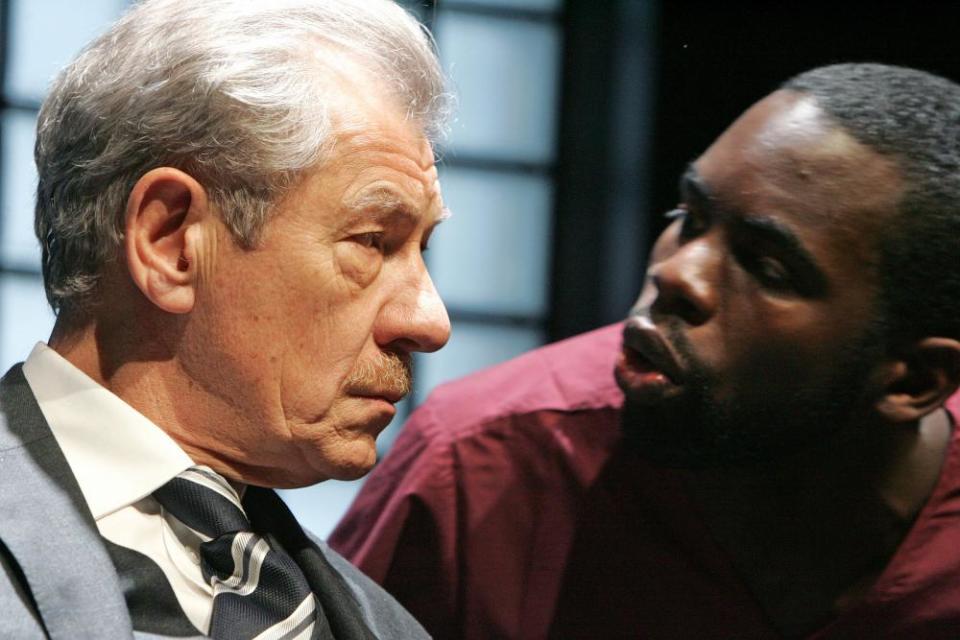

He began his career onstage, delivering grounded performances in Prayer Room alongside Riz Ahmed, Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange, and The Cut opposite Ian McKellen. Over the past two decades he has popped up in homegrown TV dramas including Holby City, Doctors, The Bill, Death in Paradise and Rev. After relocating from his native London to LA in 2017, he has landed some of his biggest roles – playing alongside Idris Elba in the comedy In the Long Run and being cast in the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air reboot. During the past three years, though, he has lost four of his closest family members.

“Looking back, it’s been the hardest time of my life,” he says. “It has pushed me to confront who I am and realise that I need to honour the people in my life who made me.”

The remake of Bel-Air – Will Smith’s hit 90s sitcom – in which Akingbola stars as Geoffrey, a British butler, has unexpected similarities to the project we are talking about today: a deeply personal documentary he has made exploring his upbringing in foster care. “Bel-Air is based on the life of Benny Medina, who grew up in the US care system and who was taken in for a time by a white family,” Akingbola says. “I realised that when I used to watch the Fresh Prince, I would identify with Will Smith’s character – this boy dislocated from his usual world into a totally unfamiliar environment.”

Akingbola, 44, was born to Nigerian parents who relocated to the UK in 1967. The youngest of four siblings, he was brought up in Plaistow, east London, for the first two years of his life. It was a tumultuous time – not only were his parents struggling to make a new life for themselves in a country rife with racism, but his mother, Eunice, had undiagnosed schizophrenia. Akingbola’s father interpreted Eunice’s symptoms as evidence of an affair, and when she became pregnant with Jimmy he singled him out as the result of her infidelity.

By 1980, when Akingbola was two, his parents were divorced and Eunice had been given custody of Jimmy, while his father had taken out an injunction to restrict her from visiting her other children. She struggled to cope with her mental health and the demands of being a single parent. Not long after Jimmy was separated from his siblings, Eunice took him to the social security office in Plaistow and left him there.

“I was put into a children’s home and it was there that a white family, the Crowes, came to visit and decided to foster me,” he says. “From the age of two to 16 I was with them; their unconditional love raised me.”

In the past three years, Akingbola’s biological parents, his foster father, Dennis, and his older brother, Segun, have all died. These collapsing foundations of his mixed family propel the subject matter of his new film, Handle With Care. Looking back at the complicated – and often uncomfortable – moments of his past, he produces a touching meditation on the nature of family, discussing with his three Crowe siblings and his two surviving Akingbola siblings their differing upbringings, the implications of being a black child in a white family, and the changes needed to ensure that looked-after children are protected.

“When it comes to stories about care, it always feels like the narrative is one-sided and focused on trauma, but I wanted to make a film about love and hopefulness,” he says. “I didn’t want it to be a clickbait story of a white family with a black kid; I wanted to make the film that the 15-year-old me needed to see – acknowledging the difficulties, but also showing that how you started in life doesn’t have to dictate your present or future.”

Akingbola beams as he explains one of his motives in making the film: to thank his unassuming foster mum, Gloria. “I’d never spoken to her about her reasons for taking me in and I really just wanted to show my appreciation,” he says. “She’s always thought what she did was nothing – that anyone else would do the same – but I am who I am because of her. We were really on our own, since one social worker told her that I should never have even been placed with a white family, but she loved me and all of her decisions were motivated from that place of care.”

There were still difficulties, of course. Akingbola describes how he struggled to integrate his black identity as a child, even briefly changing his surname to Crowe. “I was wrestling with that feeling of abandonment and I thought changing my name would help me feel part of the family,” he says. It was through seeing role models such as Sidney Poitier on screen and reading about black history that he says he came to an understanding of himself and, as an 11-year-old, reverted to his real name. Yet, in that time, he had also grown adept at compartmentalising aspects of his life that he didn’t know how to confront.

My brother went to a school 10 minutes up the road from mine. Friends would tell me they had met him, but I still hadn’t

“From the age of eight, I remember that I could explain to people how I was fostered, rather than adopted, and that I lived with a white family,” he says. “But the more I had to recount that monologue, the harder it got. I was sick of explaining – I just wanted to be a kid.” The visibility of being a dark-skinned black child in a white family meant that Akingbola was always justifying his presence, especially when the Crowes would leave multicultural London for the majority-white spaces of Kent or Devon on summer holidays.

“My family loved these trips, but I would always get looks or people would murmur under their breath when we walked into shops,” he says. “It was really hard and, as a young kid, I felt and saw everything, but I couldn’t understand why it was happening. I didn’t know it was to do with the colour of my skin.”

In a confronting moment in the film, Akingbola shares his experiences of racism with his three Crowe siblings, including a time on a family holiday when he was nine and a group of young boys began name-calling when he was alone. He walked towards them to confront their behaviour, but one of them pulled out a knife. “The fear in me was electric and I ran back to my foster family straight away,” he says. “But the thing is, I didn’t say a word to them. They later told me they wished I had, as they would have done more to protect me, but I didn’t know how to explain what had just happened. I started to develop a way to deal with everything on my own instead. It felt easier like that.”

Akingbola only came to a more stable and lasting sense of belonging when he was reunited with his birth siblings. It was a long and tantalising process. “My brother Segun went to a school 10 minutes up the road from mine and friends would tell me that they had met him, but I still hadn’t,” Akingbola says. “Once, I actually saw him on the No 15 bus as it drove down the road. I had no idea what to do.” It wasn’t until his seventh birthday that Akingbola’s eldest brother, Sola, finally came to visit and, within a few years, he was reunited with the entire Akingbola clan.

“There was no conversation, it was just instant love,” he says. “We only ever had one argument about who had it better, but I learned that, even though they got to be together, it was really tough for them, too, in a single-parent household. It was hard on both sides.”

His father, however, remained suspicious of Jimmy’s paternity. Even though they reconciled, and as a teenager Akingbola visited Nigeria with him, his father refused to take a DNA test to prove to himself once and for all that Jimmy was his son.

“It was difficult,” Akingbola says with a heavy pause. “But I was lucky to have my foster father and two mothers.” Every fortnight Eunice would visit Akingbola at the Crowe home and the pair’s bond deepened as he grew older. “We had an instant connection,” he smiles. “I read in my papers from social services how she had felt overwhelmed and couldn’t take care of me, but all I remember is the laughter and love we had together. She had a mysterious side to her, but we could just sit in the same room and exist together for hours.”

Akingbola remained fostered, rather than adopted, as Gloria wished to respect the status that he and Eunice had as a birth mother and son. “Gloria made that decision from such a deep place of love and understanding,” he says. “Her and Eunice always got along so well and she understood how I needed them both.”

With the number of looked-after children in England increasing by more than 15% between 2015 and 2020 and the percentage of looked-after children who were from black, mixed and other ethnic groups also rising, Akingbola is all too aware that his upbringing will resonate with thousands of children and adults.

“I may have had a difficult start, but I was lucky,” he says. “There urgently needs to be more funding in the care sector and there also needs to be a shift in how we perceive those who have been looked after. We’re still capable of living happy and fulfilling lives.”

During the film, the Olympian athlete Kriss Akabusi provides a perfect example of the capacity to overcome even the bleakest of circumstances. He talks movingly with Akingbola about his experiences of abuse in foster homes, while sitting surrounded by his sporting trophies. “It was really important for me to show vulnerability in this film, to see two black men being emotional,” Akingbola says. “Through leaning into those uncomfortable moments, there is hope that things can get better.”

Although he is single, Akingbola says the experience of making the film has made him more determined to adopt or foster – “We need to love these children, no matter where they’re from” – and to continue to use his platform to raise awareness. “I don’t want to be known as just ‘the kid from care’, but there is still so much more to be told,” he says. “I’d like to make another film about fostering and adoption for black parents and the experience for kids today. Until then, this is my story, my love letter to all my family – whether we share the same blood or not.”

• Jimmy Akingbola Handle With Care is on ITV at 9pm on 1 November

Yahoo News

Yahoo News