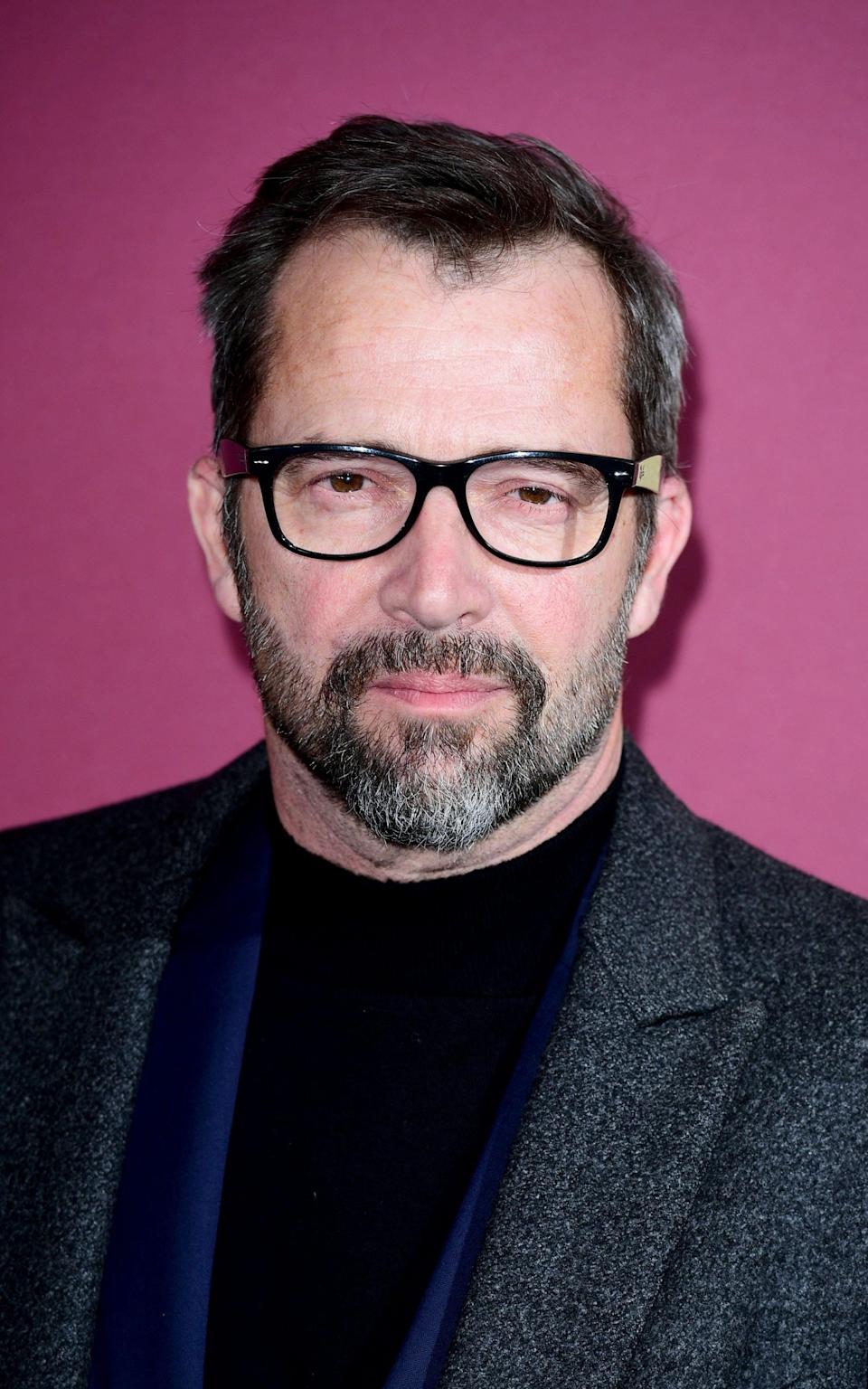

James Purefoy: ‘I was finding it difficult to have proper, intimate relationships with women’

The actor James Purefoy refers to crying as “leaking”, which he promptly begins to do just 30 seconds into our interview. He has come on to my Mad World podcast to talk about his new movie, Fisherman’s Friends: One and For All, which is ostensibly about a bunch of Cornish blokes who sing sea shanties, but really about the fragile issue that is male mental health. And the subject has set him off. I search in my handbag for a tissue, which he gratefully receives, before explaining the reason for his tears: he began filming the movie just a week after his father’s funeral last year.

“It’s something I haven’t talked about,” the 58-year-old says. “I should. It was a really strange experience shooting that film, because the big engine of the character I was playing was his father dying. And it made me really have to confront a lot of stuff.”

Purefoy, whose father was 90 when he died, compares the grieving process to a “kind of scarring”: “You scab over and then sometimes somebody picks at it or you pick at it. And then, slowly but surely, the scab comes off and you scar over. It’s not quite as painful anymore. But I was very fresh. Sometimes during the making of the film, I had to stop takes because there were tears streaming down my face, but I wasn’t in the right moment for where my character was in his grief, which was about a year on. Mine was really fresh and really raw, whereas his had time to scab over a bit. And so the two worlds were colliding in a really strange and difficult way.”

We talk a little about his parents. He was incredibly close to his mother, who died a few years ago, but he never quite managed it with his dad. “I went on holiday with him twice in my life. It wasn’t malign. He wasn’t harsh. I mean, the thing about my dad was that he was vague. I don’t want to upset my brothers or sisters. He was just a bit… I’m not sure he ever said he loved me. I mean, I know he did…”

Though the group of Cornish fishermen in the film struggle to talk about their feelings, Purefoy has no such trouble, having spent a couple of years on a therapist’s couch in his late twenties. “I went through a patch where things were really bad and I was behaving in a way…” he pauses for a moment. “Well, let’s not go into details because there are [other] people involved. But I was behaving in a way that I wasn’t happy with.” So he went into therapy.

“For a couple of years we sat down at 11 on a Saturday morning and talked with varying degrees of success. It’s a fascinating process, therapy. Really interesting. And I did get to the bottom of why I was finding it difficult to have proper, intimate relationships with people, with women, which we will probably get into in a minute.”

Shall we get into it now, I suggest? “Well, it was going to boarding school, I suppose.” He seems lighter almost the moment he says it. He was seven when he was sent to Sherborne, in Dorset, an institution he describes now as a “frightening place”. The headmaster, Robin Lindsay, was stopped from teaching in 1998 after being described as a “fixated paedophile”, but he was never charged before his death in 2016. The case was part of the massive and ongoing Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, chaired by Professor Alex Jay, part of which was published last month. Purefoy describes Lindsay as a “terrifying, bullying headmaster”. “There were various other sex offenders at the school. It was a really scary place.”

He describes returning to school at the end of the holidays. “I used to vomit as I got out of the car. It was fear. Terrible fear.” He wasn’t sexually abused by Lindsay – he believes that, because his mother had been friends with Lindsay, he was spared – but he remembers “touching, staring, looking. Him [Lindsay] dressing up in women’s clothes. It was just all deeply inappropriate and wrong.”

Purefoy has come to think of boarding schools back then “as a way to cauterise people’s emotions, so they could be sent off to the empire, watch horrific things happen and be able to follow orders”.

“I think they were for people who didn’t like children very much,” he continues. “Who didn’t want to be around their kids. Get rid of them. See them off. I think one of the things that I find astonishing, even now, is I know of parents who will say that their kids are going off to boarding school aged seven and they know. They can’t not have heard how damaging it is to be sent away at that age. That’s what I find astonishing; that there are boarding schools up and down this country full of seven-year-olds, and those parents know what they’re doing and they’re doing it willingly. Although, when they get to 13, I can sort of see it, especially if a kid wants to.”

In the late 1990s, Purefoy had a son, Joseph, with the actress Holly Aird. (He is now married to the documentary maker Jessica Adams, with whom he has a daughter and twin boys). Joseph begged to be sent to a boarding school as a teenager. “What that says about me as a parent, I don’t know. But he wanted to go and he enjoyed it. If he had ever said ‘I’ve had enough’, I would have pulled him out in an instant.”

Purefoy sees his own experience of being sent off to Sherborne at seven as “abandonment”. His father, who came from landed gentry, had gone to Harrow and had a terrible time. “As he left, he asked the taxi driver to stop at the end of the drive so he could put his feet out and shake the dust off his shoes, vowing never to look at that place again.” A theatrical beat passes. “Until June 3, 1964, when I was born and he immediately put me down for it.”

“Why would you do that?” Purefoy asks, his face a picture of incredulity. His parents split up when he was four. He went to live with his mother in Somerset, and she wanted him nearby, so Sherborne it was. “And you spend a lot of time in that therapy room being quite angry about that until you come to the realisation that they were just doing what thousands of other parents were doing. There was no malignant side to it.” But you were unsafe, I say. “Without a shadow of a doubt. I was bullied very badly. There were a couple of lads who saw it as their job to make my life a misery.”

But he was too scared to raise it with anyone. He went on to Sherborne’s secondary school where he endured the physical abuse of caning. “For some time I held a record of having the most canings in a term.” He was angry and academically disengaged. “I endeavoured to get thrown out.” He did this, aged 16, by getting drunk and stealing a combine harvester. At home, his mother told him he needed to get a job, so he went and worked in the local hospital as a porter, before becoming a trainee mortician, of all things. We might have lost Purefoy to the morgue had it not been for an intervention from his father, who asked him to come and live with him so he could attend a nearby college and get some qualifications.

“I did try out some courses,” he says. But as soon as Purefoy saw the drama studio, he knew he had to be part of it. “I looked through the window and there were four flamboyantly dressed boys and 12 rather gorgeous girls. And I thought: ‘Well that’s marvellous!’ I was like a kid in a sweet shop. So I went and joined them, and then I got cast as Romeo. It was the Billy Elliott thing. The electricity [in the theatre]. I thought I could really do this.”

He trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama, before joining the RSC. He has become one of the UK’s most versatile and prolific actors, starring in everything from period dramas (Vanity Fair, alongside Reese Witherspoon) to blockbusters (John Carter, alongside Keanu Reeves) to cult classics (A Knight’s Tale, alongside Heath Ledger). He is a familiar face to both young and old, with starring roles in Netflix’s Sex Education and the HBO megaseries Rome. But he is remarkably unpretentious about his craft. “I used to be really obsessed with reviews and numbers and marketing strategies, and I became so endlessly disappointed. So about five years ago, I went, just forget all of that and concentrate on what happens when you get the green light to go on stage. Just be as simple and as present as you possibly can.”

He felt uncomfortable using his real grief as fuel for his character in Fishermen’s Friends. “Because then you feel really soiled. You’re using it in some terrible way, to entertain people.” I say that maybe seeing people experiencing grief on screen helps them to process their own, off screen. He nods. “One of the things that you can do as an actor is you can make people feel less alone. Because you’re putting something out there, often a vulnerable thing.”

He talks about the bit in King Lear where Edgar comes across his father with his eyes ripped out. “He says it’s the very worst, what he has seen. And then he checks himself and he says: the worst is not/ So long as we can say ‘this is the worst’.” Purefoy shakes his head in admiration. “Right there, 500 years before Freud, Shakespeare is saying: ‘If you can articulate your pain, it’s not the end of the line. It is only the end of the line when all you are is a howling beast. But while we have the power of articulation, and language, we have hope.’”

Fishermen’s Friends: One and For All is released in cinemas on August 19

You can listen to the full conversation with James Purefoy on Bryony Gordon’s Mad World podcast using the audio player at the top of this article, or on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast app.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News