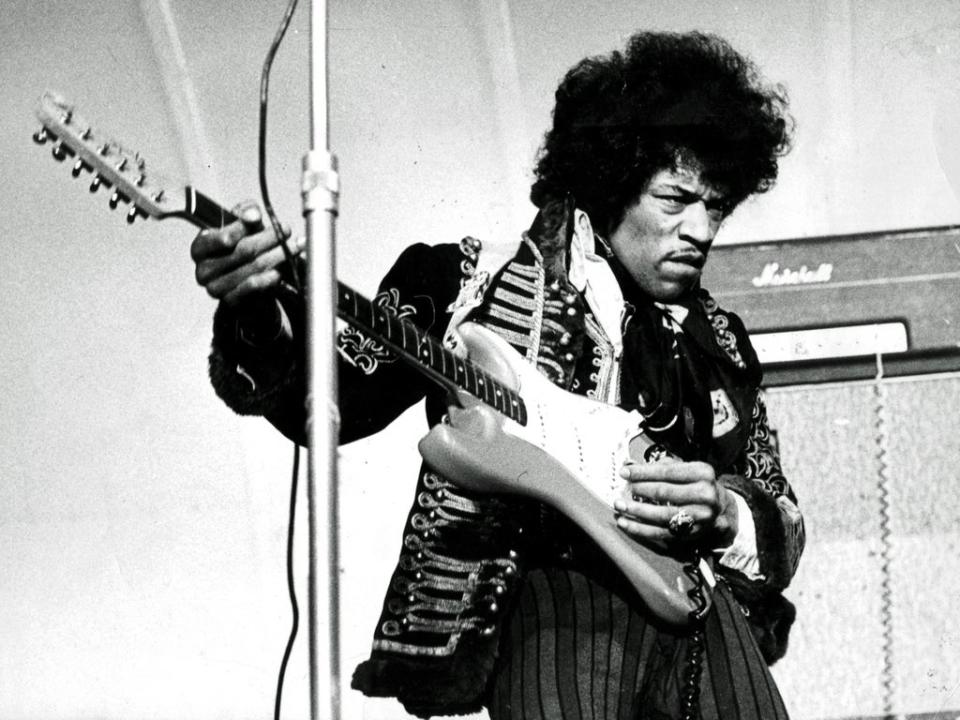

Jimi Hendrix, fire hazards and Saturday Night Live: Rock’n’roll’s raucous history of trashing guitars

On 31 March 1967, as the flames shot four feet into the air from the strings of Jimi Hendrix’s guitar, it looked, to the stunned crowd at London’s Finsbury Park Astoria, like part psychedelic shaman ceremony, part pyromaniac on the loose. The Jimi Hendrix Experience were closing their support set for The Walker Brothers, with a new song called “Fire”, when Hendrix took a guitar drenched in lighter fluid, laid it down centre stage, and struck a match.

Fifty-five years ago today, this scorching act raised Hendrix to a new level of Sixties rock mythology. (The resulting fireball charred his hands and had an emcee rushing to extinguish the flames.) Reviewers dubbed him the “Black Elvis”, and when he repeated the stunt at the Monterey Pop Festival two months later in an attempt to follow The Who’s stage-trashing antics, an iconic photo was taken that would come to define the wildfire creativity and untamed attitudes of the era. It made Hendrix not just a star in the US but the high priest of onstage destruction, and set a countercultural precedent for instrument obliteration.

Why did he do it? “I decided to destroy my guitar at the end of a song as a sacrifice,” he once said. “You sacrifice things you love. I love my guitar.”

Inspired by The Who’s Pete Townshend (and depending on his mood), Hendrix had already taken to smashing up his instrument at the end of gigs, after one had cracked as he climbed back onto the stage at a show earlier that year. The idea of torching a guitar had come up in a knockabout conversation about publicity ideas with NME writer Keith Altham before the Astoria show, although Hendrix’s own suggestion had been to “smash up an elephant”. But it soon took on a fundamental significance for rock music.

Hendrix immolating that first Fender Stratocaster – reputedly saved and restored by Frank Zappa, but definitely sold for £280,000 at auction in 2008 – became a physical representation of the elemental power of the instrument, connecting the primal emotions of rock’n’roll to the dark mysticism of the ancients. It evoked the sinister story of Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil, and helped set rock on a road into cabalistic territory, where Black Sabbath could sing of ghoulish visitations and figures like David Bowie and Jimmy Page could flaunt Aleister Crowley fascinations and dabble in the occult.

By 1967, instrument destruction had become a key component in giving rock’n’roll its parent-scaring attitude of danger and rebellion. Yet the practice predates the genre – country player Ira Louvin was reportedly smashing up out-of-tune mandolins as far back as the 1940s – and it may even have originated as an anti-rock statement. The earliest example historians quote of a guitar being smashed dates from 1956, when big-band trumpeter Rocky Rockwell renamed himself “Rockin’ Rocky Rockwell” and shattered an acoustic guitar over his knee at the end of a sarcastic cover of Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog” on US variety show The Lawrence Welk Show.

The rock’n’rollers soon adopted the idea, though, and upped the financial stakes. Several, possibly apocryphal, tales involve notable keyboard abuser Jerry Lee Lewis finishing live performances of “Great Balls Of Fire” in the 1950s by setting his piano aflame.

Early in the 1960s, however, destroying instruments was largely the domain of high art. Nam June Paik smashed a violin in one smooth blow in a piece titled One for Violin Solo in 1962. Robin Page – another artist who was part of the avant garde Fluxus movement with Paik – kicked his guitar out of the Institute of Contemporary Arts and down the street until it disintegrated for Guitar Piece the same year. And future Velvet Underground experimenteer John Cale took an axe to his piano at the Eastman Conservatory, Massachusetts, in 1963.

These artists’ intention was to destroy and reconstruct the classical orthodoxy. Such displays inspired Townshend to apply the same attitude to rock’n’roll after accidentally rupturing his first Rickenbacker against the ceiling of the Railway Tavern in Harrow & Wealdstone in September 1964.

“I was expecting everybody to go, ‘Wow, he’s broken his guitar,’” he told Rolling Stone, “but nobody did anything, which made me kind of angry in a way, and determined to get this precious event noticed by the audience.” They certainly noticed when he then hammered the guitar to smithereens against the floor and amp. “I smashed this guitar and jumped all over the bits, and then picked up the 12-string and carried on as though nothing had happened,” he said in an issue of Sound International in 1980, “and the next day the place was packed.”

Guitar demolition became a regular form of auto-destructive art for Townshend – a student of German artist Gustav Metzger, who originated the form – and was adopted with no little enthusiasm by The Who’s borderline maniacal drummer, Keith Moon. As Townshend started redefining the word “axe” front of stage, Moon would cheerfully wreck his drum kits behind him, sometimes at a rate of two a night. His antics reached their notorious peak at the end of a performance of “My Generation” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967, when Moon set off a bass drum full of explosives. The explosion set Townshend’s hair on fire – possibly contributing to lifelong tinnitus – and made fellow guest Bette Davis faint.

The act of axicide went mainstream when Jeff Beck stamped a sunburst Hofner Senator to bits in the film Blow Up in 1966, and soon became a regular occurrence during hard rock shows of the 1970s, with numerous guitars meeting violent ends at the hands of Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore or Paul Stanley of Kiss. “The idea of almost ritualistically smashing a guitar is something so cool, and touches a nerve in so many people, that it seemed like a great way to put a period or to dot the ‘I’ or cross the ‘T’ at the end of a show,” Stanley told Allmusic, “that this is finite, that this is over, it’s the climax.”

These pre-planned moments of showmanship, as visceral as they were, played into the romantic notion of rock’n’roll as a greater force than anything used to create it. That once a song was finished, the instrument had served its ultimate purpose; that the music, the gig, the moment was more valuable than any guitar. It’s why Prince flung his guitar so far in the air at the end of his scorching solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” at the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony that it seemingly never came down.

It’s why Nirvana stacked their drum kit at the front of the stage at the end of their 1992 Reading Festival set and lobbed their guitars at it, and Craig Nicholls of The Vines harpooned his guitar straight through the drum kit live on David Letterman in 2002. And it’s why, last year, Phoebe Bridgers set about wrecking her Danelectro Dano on Saturday Night Live (SNL), for which she received criticism after being so polite about it that she notified the manufacturers first. “I told Danelectro I was going to do it,” she confessed during a Twitter spat with David Crosby about the incident. “They wished me luck and told me they’re hard to break.”

More spontaneous instances of musicians turning Stratocasters into sledgehammers tend to be the result of onstage frustration. The iconic cover of The Clash’s London Calling album features a Pennie Smith shot of Paul Simonon smashing his bass into the stage in anger at security at the New York Palladium, who had killed the vibe of the gig by refusing to let fans leave their seats. “We used to get cheap Fenders from CBS,” he said later. “They were newer models, quite light and insubstantial. But the one I smashed that night was a great bass, a Fender Precision, about £160, one of the older, heavy, solid models, so I did regret breaking it.”

Some experts actually consider instrument demolition to be an extreme outward display of performance anxiety. “Performing artists put an enormous amount of effort into performance,” says music psychotherapist Tamsin Embleton, author of the forthcoming book Touring and Mental Health: The Music Industry Manual. “It takes a lot of mental and physical preparation, vulnerability, courage and exertion to perform ... there can be a lot riding on the performance’s success. But, of course, shows don’t always go to plan.

“Sometimes the audience disappoints – they’re reserved, disinterested, mocking, or otherwise not willing to ‘go there’ with you. At these times it can be crushingly disappointing – as if the effort you’ve put in to give so much of yourself has been squandered. A performer might feel rejected or ashamed if the show doesn’t go well – as if somehow the survival of their self, or their career, has been compromised. Shame and rejection are powerful emotions that can lie underneath anger.”

Embleton also highlights the need for musicians to be focused on the music and in control of their performance in such high-pressure environments, often taking out their frustration at malfunctioning equipment, disturbances or shoddy treatment on their instruments. Which explains why so many guitar trashings are filmed or televised – Win Butler of Arcade Fire breaking a string on SNL spelt the end of the entire instrument in a cloud of splinters, for instance – and why electro-rock band Nine Inch Nails (NIN) would regularly trash any piece of equipment that failed onstage during their 1991 Lollapalooza tour, with frontman Trent Reznor sometimes getting through ten guitars per gig and even kicking the keys off his synthesiser.

After a while they learned to smash up their gear without ruining it all

Muse’s former tour manager Glen Rowe

NIN’s crew tallied up 137 ruined axes on that tour, a record only beaten by the British band Muse’s serial guitar slaughterer Matt Bellamy, who totalled 140 guitars in 2004 alone. His destructive tendencies had begun at early gigs, where he’d simply destroy any out-of-tune guitar that his inexperienced crew would hand him. Over time, however, it became an act of rebellious exhilaration, Bellamy often ending shows by spearing drummer Dom Howard’s kit with his guitar neck, or, at one show I witnessed in Austria, almost decapitating an unsuspecting security guard with a frisbeed cymbal.

With the cost of replacing instruments on chaotic early tours coming out of their own pockets, though, their equipment bills ran to thousands of pounds. “After a while they learned to smash up their gear without ruining it all,” Muse’s one-time tour manager Glen Rowe told me for my book Out of This World: The Story of Muse. “Because after a while they weren’t frustrated by their equipment breaking down; it was more of a celebration.”

Ritzy Bryan of The Joy Formidable, who took to what she calls “losing” guitars during their climactic early hit “Whirring” on tours in 2010 and 2011 – even offing one during the very first song of their set at Reading 2010 – agrees that instruments die in the moments when frustration and freedom collide.

“It involves a lot of emotions sometimes,” she says. “‘Whirring’ is a song all about not feeling heard, feeling invisible, and it was a very emotional time. The greatest of shows is when you really lose yourself in those moments, where you become your most vulnerable. The combination of feeling quite emotional, quite frustrated, being in the moment, and it’s almost like another expression. It’s been a crossover – sometimes it’s felt very freeing and you feel very alive, it’s a beautiful moment of letting go and you love the way it all sounds.

“It sounds f***ing great smashing a guitar against a gong – after I got bored of smashing them into amps and the ground, we got this huge 9ft gong to give it an extra dimension of musicality. Then there’s been some times [when] it’s almost another step of wanting to hurt yourself or hurt the guitar. It’s almost like crying in public as well, because bits fly off and they hit you in the face.”

Such appetites for destruction are barely a nibble, though, compared to the all-time queen of rock’n’roll annihilation. At a 1980 show on New York’s Pier 62, punk hero Wendy O Williams of the Plasmatics – already then infamous for chainsawing guitars in half during gigs – drove a Cadillac full of explosives at the stage, bailing out seconds before the entire show went up in flames. It was what you might call “maximum Hendrix”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News