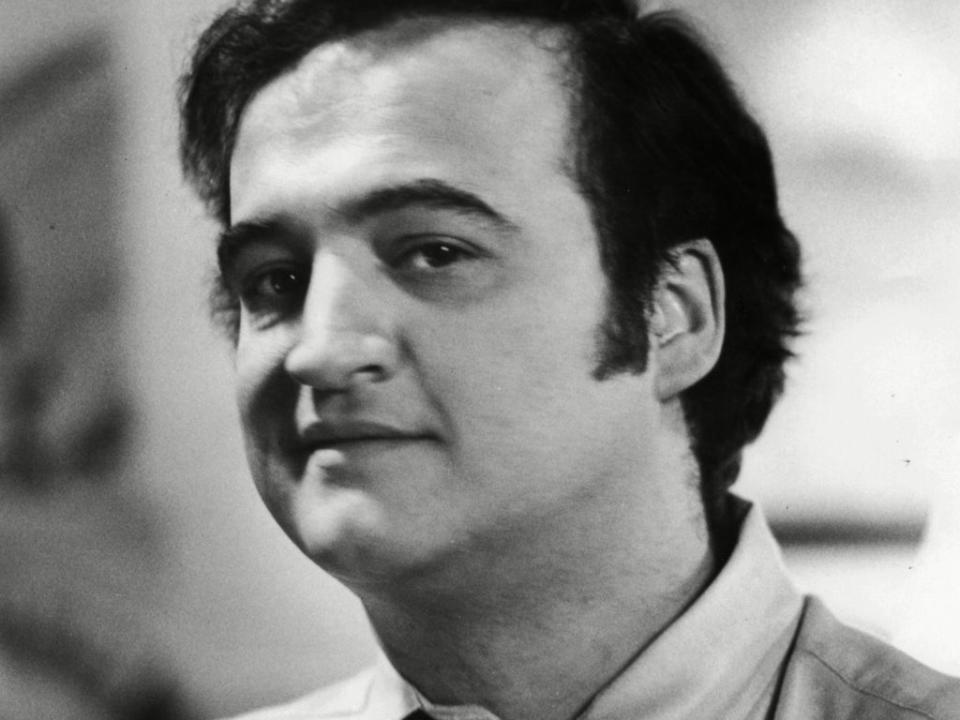

John Belushi: Remembering America’s most rebellious comic

New York, 1978, and packed houses of cinema-goers roared in amazement as the riotous toga party on screen almost burst into the aisles. National Lampoon’s Animal House was well on its way to becoming the highest grossing comedy film to date. And as this bawdy college rampage of flying beers, clumsy sex and ancient Greek wardrobe malfunctions reached its hedonistic peak, its star, the Saturday Night Live comedian John Belushi, would run from the back of the cinema to the screen, lead the audience in a rousing chant of “Toga! Toga!” and then flee through a fire exit.

Belushi played the feral 24-hour whiskey monster Bluto in Animal House and he had secretly toured the city’s picture houses in opening week to witness the excitement around the film firsthand and up the ante. Bluto was the anarchic party animal incarnate, a boorish, semi-articulate slob described by the movie’s director John Landis as part Harpo Marx, part Cookie Monster. Belushi died just four years later, 40 years ago this week, aged 33 from an overdose of cocaine and heroin in a bungalow at LA’s Chateau Marmont, after years of battling hard drug addiction. It left many under the impression that he and Bluto were virtually one and the same. But while his breakthrough big screen role undoubtedly drew on the actor’s hard-partying, sleep-when-I’m-dead attitude, it belied the depths and subtleties of this complex comic legend.

As much as Belushi was Bluto – many friends recalled how he’d regularly turn up at their homes at 3am to play loud music or drag them out on clubland adventures – he was also the energetic and passionate music fanatic “Joliet” Jake Blues of 1980’s The Blues Brothers. The dedicated romantic he played in 1981’s Continental Divide. And one of the politicised Woodstock-era radicals he’d parody onstage in National Lampoon Lemmings in 1973: his very first television appearance saw him being knocked to the ground by jets of tear gas on the news while protesting the Vietnam War at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago.

Belushi was, by all accounts, a gregarious and generous accomplice who’d often insist on his friends getting jobs alongside him as his star rose. A dedicated husband to his school sweetheart Judy. An ambitious and competitive talent determined to break the glass ceiling on his working class immigrant background. A born scene stealer with an innate, eye-catching flair for improvisation and physical comedy. An unlikely expert on Napoleon. And a man whose personal cracks were inevitably widened by the money, pressure and excesses that accompanied becoming, for a few short years, the biggest star in – and best buddy of – America.

Born into an Albanian family in Chicago in 1949, allegedly well on his way to a full beard at birth, Belushi always had an eye for performance. More class impressionist than clown, he began improvising sketches and standup routines during high-school variety shows. In one memorable skit, he dressed as a blue fairy with a tiny wand, improvising ballet moves in a tutu. A potential career as a serious theatre actor was short lived; as a high-school graduation present, Belushi was taken to a show at Chicago’s Second City, an early improvisational comedy venue where Joan Rivers had earned her spurs. “When he walked out of the theatre that night it was as if a light had gone on in his head,” Judy wrote in her 2005 oral history of his life, Belushi.

Youthful self-belief and determination kicked in. By studying Second City revues each week and then performing them verbatim with his own University Of Illinois comedy troupe, the West Compass Players, Belushi soon came to the attention of Second City’s directors, keen to meet this cocky yet endearing young upstart. Before college was up, he’d dropped out to join Second City’s new improv cast, bringing a countercultural edge to their somewhat safe, intellectual humour, and dominating scene after scene with his extreme physical and gross-out comedy, magnetic stage presence and unexpected bursts of his staggering Joe Cocker impersonation. He’d steal sketches he barely spoke in – a role as the Angel Gabriel, for instance, for which he made an extremely slow, silent entrance flapping a pair of tiny wings with each step; risk injury by throwing himself into scenery; and improvise heroin overdoses when he had nothing to do in a scene. One skit acted as a kind of Bluto blueprint: entitled “The World’s Most Obnoxious Houseguest”, Belushi played a shy girl’s new boyfriend being introduced to her parents, entering with the line “Man, I just laid the biggest t*** of my life in your toilet…”

“John inserted himself into practically every sketch in a two-hour show,” National Lampoon editor Tony Hendra said in Belushi, recalling his 1972 trip to Chicago to check John out for a potential role in the magazine’s off-Broadway Woodstock pastiche Lemmings. “If he felt like entering a scene, he did it without rhyme or reason, with irrelevant characters, listening to no one, taking the action wherever it would leave him front and centre.” The perfect performer to bring the Lampoon’s risqué and extreme humour to the stage, Belushi similarly stole Lemmings, alongside Chevy Chase and Christopher Guest, as the Satanic MC encouraging the audience to eat each other in the name of hippie liberation.

Swiftly becoming National Lampoon’s prime asset, Belushi recruited old Chicago associates including Harold Ramis, Gilda Radner and Bill Murray to write and perform on the magazine’s radio show and revue. “There you had the essential struts, pillars and crutches of the American comedy industry as we know it today,” said Dan Ackroyd, another Chicago player who would also be drawn to NYC in Belushi’s slipstream. Though notorious for being able to hold it together onstage while high on pot or hallucinogens, Belushi became the focused and professional fulcrum of this revolving troupe, and the likes of Chase and ex-Lampoon editor Michael O’Donoghue lobbied producer Lorne Michaels hard to include him alongside themselves, Ackroyd, Radner and others in the debut cast of Saturday Night Live in 1975.

Though initially reluctant to sell his improvisational soul to television, Belushi won his place with an audition piece involving a samurai warrior playing pool with his sword – a character that would become legendary in the show’s early seasons as the katana-flailing business proprietor in sketches such as “Samurai Hotel”, “Samurai Delicatessen” and “Samurai Optometrist”. Alongside his portrayals of Captain Kirk, Marlon Brando and a weatherman with anger issues, the samurai made Belushi the byword for manic, rebellious comedy, a figurehead for the anger, ambition and frustration of America’s outsider immigrants and, as the show’s ratings rocketed, a household name. Early magazine profiles dubbed him The Most Dangerous Man On TV.

With the show’s success came both intense pressure and star money, $1,600 (£1,200) a week, which played into the party-loving conviviality of a man who confessed to Crawdaddy magazine, “when in doubt, I floor it..” Increasingly fuelled by cocaine, he became the life and soul of a non-stop one-man party. He’d hire limousines to ferry friends around Manhattan on clubland adventures; if one companion bailed at 4am, he’d turn up at another friend’s apartment and drag them out until beyond dawn. SNL writer Marilyn Suzanne Miller described him as someone who “wanted everybody to be having a good time wherever he was”. “Some nights,” writer Mitch Glazer said in Belushi, “there’d be a knock at your door, you’d cautiously open it a crack… and suddenly all the forces of nature would blow into your apartment, use your phone and suck you out into the night.”

It was a cruder, more neanderthal version of Belushi’s own character, then, that was written into Animal House for him. As the mustard-smeared, toga-clad albatross in a frat house’s doomed attempts to avoid mass expulsion, Bluto would happily eat from canteen bins, down entire bottles of whiskey, spy on undressing girls from unsecured ladders and punch mouthfuls of food into the faces of their rival house in an impression of a zit. Onscreen, the ultimate slob, but offscreen, despite exhausting commutes between Oregon and NYC to maintain his SNL schedule, Belushi drove the film, forging a band-of-brothers camaraderie on set and giving Bluto a sense of party hero nobility. His attempts to cheer up Stephen Furst’s weeping Flounder by sweetly crushing a can against his forehead was, friends claimed, the closest to Belushi’s true nature ever captured on film.

As Animal House worked its way towards cinemas in 1978, Belushi found himself on a mission from the blues gods. Over the course of a bonding cross-country road trip with blues aficionado Ackroyd and a trip to see an R’n’B band while shooting Animal House, Belushi – previously a Stones and heavy metal fanatic – had a Damascene conversion. His late-night home invasions became impromptu playback parties for his pockets full of blues cassettes, and he began making guest appearances singing with local bands. He and Ackroyd would soon take over a dilapidated bar in Brooklyn, dubbed The Blues Bar, where the SNL cast could party and jam all night without being recognised. David Bowie and Francis Ford Coppola dropped by and Keith Richards was an occasional barman. “[Belushi] threw himself into the blues like a hurricane,” National Lampoon Radio Hour engineer Bob Tischler told Belushi. “It became more than just an attitude,” Judy added, “it turned into a full-blown alter-ego.”

It was time to get the band together. Having previously sung a blues tune on the show dressed as bees in 1976, Ackroyd and Belushi officially launched The Blues Brothers – with Ackroyd as Elwood Blues and Belushi as his back-flipping brother “Joliet” Jake – as musical guests on the show in April 1978. This energetic song-and-dance homage to classic blues and rock’n’roll, with a look inspired by the suit, hat and shades of old John Lee Hooker records, was no throwaway pastiche; Jake and Elwood were personifications of Ackroyd and Belushi’s genuine shared passion for the music, and their commitment was so apparent that they went down a storm.

Building a backing band of revered blues names such as Donald “Duck” Dunn, Steve “The Colonel” Cropper and Matt “Guitar” Murphy, they started playing full concerts and released a live debut album Briefcase Full of Blues, recorded while blowing headliner Steve Martin offstage at the Los Angeles Universal Amphitheatre. “The Blues Brothers went from hobby to obsession to national phenomenon in less than a year,” Ackroyd said; the album went platinum in a week and hit Number One in America en route to 3 million sales. That’s just as Animal House was breaking box office records and, with 20 million viewers, and SNL was the biggest late-night show on American TV. At 30, Belushi was a millionaire taking private jets to a summer home in Martha’s Vineyard, one of few performers ever to hit the top of the music, movie and TV worlds at the same time, and undeniably the biggest star of 1978.

A Blues Brothers movie was green-lit before Ackroyd had even written his monstrous 324-page script, but it proved a mixed blessing for Belushi. Cinematically the 1980 film remains his finest hour, as Jake and Elwood chase the spirit of the blues around Chicago with the police, country rednecks and Nazis on their tail. He was starring and performing alongside such legends as Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, James Brown and John Lee Hooker – fading blues and soul stars who credit Belushi and The Blues Brothers for reviving their careers – and returning to film in Chicago, he found himself a local hero, able to hail passing police cars to drive him home.

But cocaine was becoming a serious issue. Before one SNL show, after a night out with The Rolling Stones, Belushi’s lungs began filling with fluid and he barely made it onto the set (he’d quit the show soon afterwards). Filming Stephen Spielberg’s 1979 wartime comedy turkey 1941, he’d go awol or injure himself falling from the wings of planes. And when he was in Chicago filming The Blues Brothers, all of his old networks of contacts reopened, the cast and crew were awash with drugs and everybody in town wanted to palm Bluto a bag of blow in a handshake, just to see how wild he’d get.

The very unpredictability that had made Belushi a star now made him impossible to control. Director John Landis claimed that only six days of the six-month shoot were lost to drugs, but other stories portray an addict in sharp decline. Scenes were constantly delayed and the budget spiralled because Belushi – mixing cocaine with alcohol and Quaaludes – was incapable of, or unwilling to perform, or simply couldn’t be found. He’d bawl out co-star Carrie Fisher for questioning his cocaine use, or even pass out mid-scene. Landis recalls punching a drug-dazed and ashamed Belushi to the ground when he refused to come out of a trailer akin to the final scenes of Scarface: mounds of cocaine, pools of spilt cognac, urine on the floor. One doctor estimated that, from his physical condition and rate of intake, he had a couple of years to live; his friends petitioned his manager Bernie Brillstein to have him involuntarily committed to hospital in the hope of saving him, but any attempts to confront him were met with rage and denial.

After The Blues Brothers wrapped, however, the death of his grandmother Nena gave John the jolt he needed to admit to his problem. He agreed to hire a former Secret Service operative named Smokey, who had helped the Eagles’ Joe Walsh stay clean, to break his habits. Initially the pair played cat and mouse games, as Smokey swept toilet cubicles and conducted pocket searches to confiscate gram after gram being slipped to Belushi, and John continually tried to give him the slip. But eventually the plan worked; as The Blues Brothers hit the road with what Ackroyd called “the third greatest R&B revue in the world” to support their $80m hit movie (which would later spawn the entire House Of Blues nightclub chain), Belushi cartwheeled onstage to play two-hour shows exuberantly clean.

He took up training and karate and his Martha’s Vineyard hideaway became a healthy and happy haven from temptation. At the 1981 wrap party for his next movie Continental Divide, a well-received romantic comedy he hoped would broaden his scope as an actor, he was handed eleven vials of cocaine and flushed them all. Smokey considered his work done and, in March 1981, relieved himself of duty.

Sadly, Belushi’s troubles were far from over. On the set of his final film, Neighbors – another black comedy collaboration with Ackroyd – he became increasingly frustrated with Rocky director John Avildsen and relapsed. He’d refuse to leave his coke-strewn trailer unless Avildsen left the set, and his mood swings would turn violent; angry at the film’s soundtrack, he trashed the office of Columbia’s musical director, ripping the phone from the wall. “When he was clean and sober he was the most wonderful man I’ve ever known,” said Atlantic Records executive Michael Klenfner, “[but] when he was f***ed up he was as big a horror as you ever could imagine.”

Despite Neighbors flopping at the box office, Belushi’s movie future remained bright. He was set to star as Ignatius J Reilly in an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning A Confederacy of Dunces, and Ackroyd was writing a central part for him in his new script, Ghostbusters. But amid Hollywood wrangles over his next $2 million project, and with $2,500 a week set aside purely for drugs, his mood darkened, and his abusive rages and wild behaviours intensified. He became Bluto, untamed. In New York he began dragging friends to darker and seedier places on desperate drug hunts, until they stopped answering his 3am calls.

On 28 February 1982, with his wife and colleagues in New York discussing an urgent intervention and asking Smokey to return, Belushi checked into Bungalow 3 at LA’s Chateau Marmont hotel, in town to try to rescue a film project about a diamond caper in the wine region called Noble Rot from the can. According to Bob Woodward’s 1984 Belushi biography Wired, over the coming days of almost non-stop drug taking, Belushi fell in with Cathy Smith, an ex-partner of various members of The Band and Gordon Lightfoot who had turned to dealing heroin to the likes of The Stones and Hollywood figures. At Belushi’s request, Smith introduced him to speedballs – a mixture of cocaine and heroin – and administered 11 shots to him over the course of two and a half days.

On the night of March 4, having demanded $1,500 from Brillstein on the pretext of buying a new guitar, John toured regular LA haunts such as the Rainbow and On The Rox before returning to the bungalow in the early hours, where he continued partying with visitors including Smith, Robin Williams and, briefly, Robert De Niro. After injecting him with one last speedball and checking he was sleeping okay despite making choking noises, Smith left him snoring loudly at 10.15am. Around two hours later, Belushi’s fitness trainer Bill Wallace found him dead.

“I killed John Belushi,” Smith told the National Enquirer after being released from questioning. “I didn’t mean to, but I am responsible.” The interview earned her $15,000 and 15 months in jail for involuntary manslaughter. A year later, at John’s likely comic request, his friends and family placed items including a blues harp, a microphone and an unpaid IOU to Bill Murray into a dinghy on Martha’s Vineyard and gave John a mock Viking funeral.

Belushi was a man whose on camera persona and lust for life overtook him. His death marked not just the loss of one of US entertainment’s greatest comic performers but the end of an age of innocence where wild living and excess seemed to have no consequences. “The endless adolescence of the baby boom can be seen primarily through those movies,” Miller told Belushi of the string of SNL movies such as Animal House, Meatballs and Caddyshack. “They weren’t allowed to grow up, and it wrecked their lives.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News