Lessons in Love and Violence, Royal Opera House, London, review: A Rolls Royce production that could use a few tunes

George Benjamin’s last opera, Written on Skin, has had such glittering international success – notching up more productions per year than Britten’s much-loved Peter Grimes – that expectations were sky-high for the new one which has just opened at the Royal Opera House.

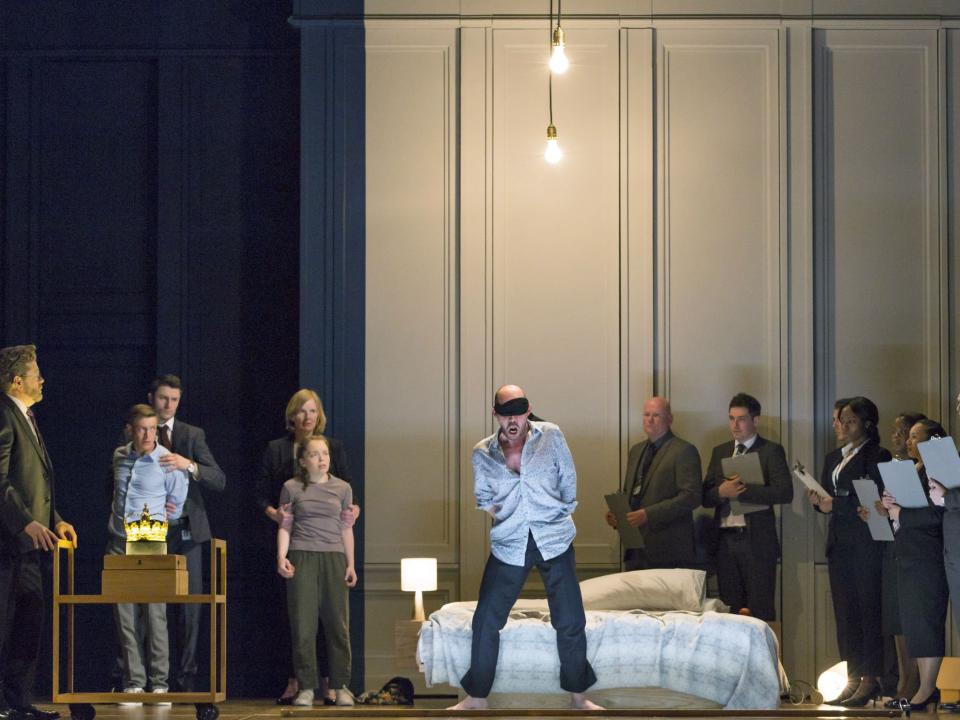

With co-producing houses in five other countries, Lessons in Love and Violence is assured of world-wide attention, despite the size and complexity of its cast, orchestration, and staging. And with Benjamin in the pit, director Katie Mitchell at the helm (as she was with Written on Skin), Vicki Mortimer in charge of design, and the amazing Barbara Hannigan in a dominant role, this is in every respect a Rolls Royce production.

Written on Skin is an old Provencal love-story which climaxes with a woman being forced to eat her dead lover’s heart. Benjamin and his regular librettist Martin Crimp have again delved into the mediaeval period, following a cue by playwright Christopher Marlowe and film-maker Derek Jarman, to tell the lurid story of King Edward II and the man alleged to have been his homosexual lover, Piers Gaveston.

Popular legend has it that Gaveston’s end came with the rectal insertion of a red-hot poker, but Mitchell confines the gore of his demise to a blood-drenched mattress; the plot here dwells on political and psychological matters.

The story encompasses both a disfunctional royal family whose misrule causes misery to its subjects, and a convoluted sado-masochistic sexual relationship between the king and his lover. Big questions are raised about public versus private, art versus life.

But Crimp’s libretto overlays everything with a quasi-poetic veneer which militates against any kind of narrative clarity. There is just one scene in which the directness of the drama ingeniously hits home, as the queen flaunts her riches in front of a miserable huddle of migrants, but too often the plot gets lost in gnomic verbiage. There is a beautifully staged play-within-a-play, but it has none of the purposeful dramatic thrust of its exemplar in Hamlet.

All this said, one can only admire the valiant ensemble performance, with Stéphane Degout’s King, Hannigan’s compelling queen, tenor Peter Hoare’s trenchant royal adviser Mortimer, and fellow-tenor Samuel Boden’s pure-toned royal successor all making the most of their very demanding parts.

Meanwhile Benjamin’s fabled brilliance as an orchestrator produces a finely-wrought sonic tapestry: it's as accessible as film music, but with original effects thanks to compositional alchemy and unfamiliar instruments including a cimbalom and steel drums. The vocal line may be relentless recitative, but the instrumental sound-world is a seductive amalgam of late-Romanticism and early-Modernism. The interludes with which the scenes are punctuated could be extracted to form the basis for a lovely orchestral suite.

Benjamin insists that he doesn’t do ‘tunes’, but I left the theatre wishing that he occasionally would.

Until May 26 (roh.org.uk)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News