I’m not stoned, I’m just writing an opera! Colm Tóibín on how he got a diva fever

When I went to live in Barcelona at the age of 20 in 1975, I thought I would get to see loads of opera. The first ticket I bought was for Puccini’s La Bohème at the Liceu, starring Montserrat Caballé as Mimi. When I found my seat, however, I discovered that I had no view at all of the stage. Standing up would not help, because there was not even enough headroom to stand.

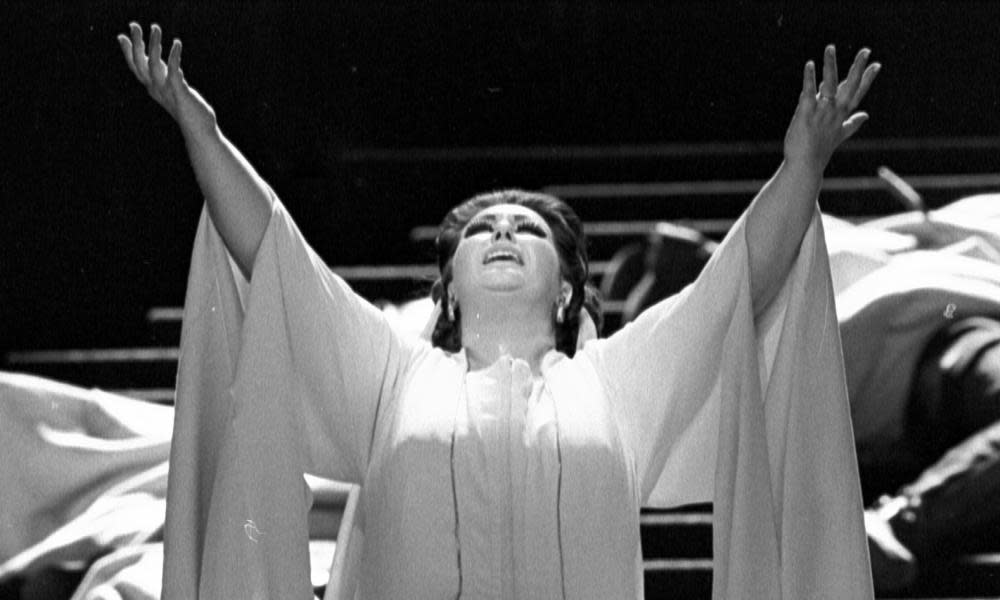

I grew sad when the music began, in the sure knowledge that the stage must be bathed in beautiful light and the costumes must be gorgeous and the set superbly crafted. But the real problem arose in act four. As Mimi sang her farewell, I could not bear it any longer. I felt a rat-like determination to see Caballé just once. I realised that leaning out from where I was would not work. So I waited until a culminating moment, Caballé’s voice at its most splendid, and I not only leaned out, but rested my two hands on the shoulders of each of the two men in front of me – and propelled myself forward like a duck. That allowed me to catch a glimpse of the stage, just one glimpse, for one second.

Bernardo Bertolucci wanted to make a film about the 'clothes burying' scene in Venice. 'The rest of the book,' he said, 'has no story!'

The men whose shoulders had been used went crazy. But by that time, I had retreated. The problem was that my leaning had been less gentle than I had planned. I had clearly ruined the experience of a great high note for two members of the audience who had paid more money than I had. When the opera ended, since they knew where I was, I did not wait for the applause. I fled like a thief into the Barcelona night.

On Good Friday in 1989, on my first visit to New York, I discovered to my delight that every single shop in the city was open. I went out to a nice restaurant for lunch. I even met a taxi driver who did not know what Good Friday was. When I tried to explain it to him, the whole sorry story sounded quite untrue, so I decided not to try that again.

Instead, I bought a $5 ticket, standing only, for Wagner’s Die Walküre at the Metropolitan Opera, with Jessye Norman and Christa Ludwig in the cast. It began at 6pm and was scheduled to last until midnight. As the lights dimmed, I saw an empty seat halfway down at the end of a row. It was one of the best seats in the house. I walked to it as though I owned it and sat like a king for the evening.

That year, new ways of using a telephone were beginning to emerge. In New York I had a friend who insisted that, if I called his number, he would have changed the message on his answering machine remotely and, thus, could tell me the name of the bar where he and his friends were gathered. After the opera, I went to a phone booth and found he was right.

At midnight, then, I zoomed downtown in a cab and found my friends in the Peter McManus pub on Seventh Avenue and we sat there drinking and talking and laughing until four in the morning. When the garbage men came to quench their thirst, we mixed in with them. I did not get home until 5.30am. In Ireland, I would have spent the day contemplating the wounds of Christ – in those years, even the pubs closed in Dublin on Good Friday. To this day, every time I pass Peter McManus’s, I think of Brünnhilde and her poor father, not to speak of the Rhine maidens. And every time I hear these maidens on record, I think of that epic night in Peter McManus’s.

Between the deprivations I experienced at the Liceu and the good luck at the Met, there was the Wexford Opera festival, which was founded in 1951. This was where I saw a live opera for the first time. I was 16 and it was the dress rehearsal of Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers. Our boarding school was on the outskirts of Wexford town, on the south-east coast of Ireland, and those who wanted to go to the opera had to assemble on a few afternoons to listen to a recording. I have a clear memory of the stereo record player being rigged up and the light from the sea shining through the long windows.

At the opera itself, what was startling was the precision of the chorus, the sharpness and closeness of the sound, and the rich yellow colour that the lighting gave the stage when the curtain came up. The soprano was called Christiane Eda-Pierre. Now, as I write this, the word motif comes back to me. In the talks about the opera each afternoon, we were told to watch for motifs, but that did not sink in then as very important. But as I sat in the Theatre Royal in Wexford, I recognised the motif that came before the first duet – though nothing had prepared me for those soaring moments when the two voices merged and moved apart and competed and merged again. The main duet seemed to rise above Wexford town itself and linger in the night air.

In the days that followed, I managed to get permission to go downtown. Wexford was full of English people, there for the opera. I had, at that time, never met any English people. They were extraordinary. I began to listen in to their conversations in White’s Coffee Shop. One man told another that he had supper with Eda-Pierre a few nights before and they had stayed up rather late and he really did hope it hadn’t affected her vocal cords. I heard two small, rotund Englishmen talking about the chorus in certain Schubert songs: should it be repeated every time? One man rather thought it should since he really did think those choruses were really rather beautiful.

For a few days after that, I went around saying “really” and “rather” until I worried that people might think that I myself was really rather peculiar. And then, more recently, the Italian composer Alberto Caruso asked me to write a libretto of The Master, my novel about Henry James, for him. Since I admired Caruso’s work and enjoyed his company, I agreed, even though I had never written a libretto before.

When The Master first came out, I had been summoned to meet the director Bernardo Bertolucci, who said he wanted to make a film of the book. He liked the scene in Venice, he said, when James and a gondolier tried to “bury” the clothes of fellow writer Constance Fenimore Woolson in the waters of the lagoon. In fact, he liked it so much, he added, that he just wanted to make a film of that. “The rest has no story!” he said dismissively.

The novel followed the shape of James’s life. It did not, as Bertolucci so kindly put it, have an actual story. For a libretto, I needed a plot. Thus, I followed what Bertolucci had said: the scene with the clothes in Venice was where the drama lay. It was the culminating moment. And thus I could centre on the relationship between James and Woolson, a close friend of his who died after jumping, or accidentally falling, from a fourth floor window in Venice in 1894.

He could be a tenor and she a mezzo. Rather than trying to tell a linear story, I would concentrate on the high moments between them, as he sought to dedicate his life to his work while also suffering from an intense loneliness, while she lived an independent life but also wanted some commitment from him. Woolson was the closest James ever had to a companion. So I was writing about doomed love, unrequited love, a misunderstanding between a man and a woman – subjects opera has embraced over the centuries.

People kept offering to take me to the best dope shop in town, as in Dublin they might offer to take you to the best pub

I worked for a few summers with Caruso dramatising some scenes. But it was only when we began to work with the director Ron Daniels that a core drama emerged. With Daniels, we took the opera to the University of Colorado at Boulder to workshop it with students. Colorado was, at the time, the only place in America that had legalised marijuana. It was unsafe to walk in the streets because most pedestrians were really rather stoned. People kept offering to take me to the best dope shop in town, as in Dublin they might offer to take you to the best pub. Having to explain that I was really rather busy writing an opera made me sound even more out of my tree than the general population of Boulder.

When Rosetta Cucchi, the new director of Wexford Festival Opera, decided to include The Master among this year’s productions, it was agreed that Caruso would conduct and that Conor Hanratty – who did a wonderful version of Bellini’s I Capuleti e i Montecchi at Wexford last year – would direct, with Thomas Birch playing Henry James.

After that production of The Pearl Fishers 51 years ago, we had to march back to the school. I remember thinking that there was a great world out there, with bright lights and soaring emotions, with people who would cross the sea to hear a singer. Fellows were having dinner with Christiane Eda-Pierre or discussing Schubert songs in earnest tones. I imagined that I would always have my nose up against the glass of this world.

If anyone had told me then that I would write the words to be put to music by a man called Caruso, to be sung in Wexford by a man playing Henry James, I would rather have thought not. I really had no evidence to believe that anything like that was going to happen.

• The Master opens at Wexford on 22 October with subsequent performances on 23, 27, 29, 30 October and 1, 3, 5 November. Wexford Festival Opera runs from 21 October until 6 November, with 80 cultural events over 17 days.

• Colm Tóibín will discuss his life and writing at a Guardian Live online event on Thursday 3 November. Book tickets here.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News