Meet Chas, he's been mad about Bowie since he was a lad

“You’ve got to talk to Chas,” says my friend Natasha. “He was there the time David got out of the car!” I go and talk to Chas, who can barely contain his excitement. “It was outside the BBC,” he says. “At Parkinson.” Right, I say: is that Parkinson the TV chat show host? “Yes,” says Chas breathlessly, keen to continue his story. “And the car pulled up. And the door opened. And David got out!” Chas’s eyes are wide open now. “And he talked to us. For about five minutes.”

Chas has the expression of someone describing winning the pools. The same sort of look you see on the faces of teenage girls in news footage about One Direction and Justin Bieber, and in those old clips of Beatlemania and Elvis concerts. But Chas is not a teenage girl. In fact he’s neither: he’s a man of 55 and he has spent the last 40 of them obsessed with David Bowie.

Chas says he has seen Bowie 200 times, in countries all over the world, including TV appearances. But that time outside Television Centre in 2002 was the best of the lot. “Because it wasn’t us going up to talk to him, like it usually is. It was him getting out to talk to us.”

I meet Chas at a small pub in Kings Cross called The Water Rats. It’s the kind of tiny pub venue where up-and-coming bands, most of whom you’ve never heard of and never will, play for around a tenner. This night is very different. It’s packed with a sell-out crowd of 250, most of whom have paid £80 to be there. Apart from the ones who paid £100 for a VIP experience, which included seeing the last 30 minutes of the sound check. And the elite group of ten who paid an extra £235 for a “three-course private dinner with wine”.

Dinner with whom? With Mike Garson, who was David Bowie’s piano player. It’s not just dinner: Mike throws in some anecdotes about his time working with Bowie, answers their questions and “hears their thoughts”. It’s probably just as well that he doesn’t hear the thoughts of one of the audience (not Chas) whose first one is that this is scraping the bottom of the barrel and disrespectful to David Bowie’s memory.

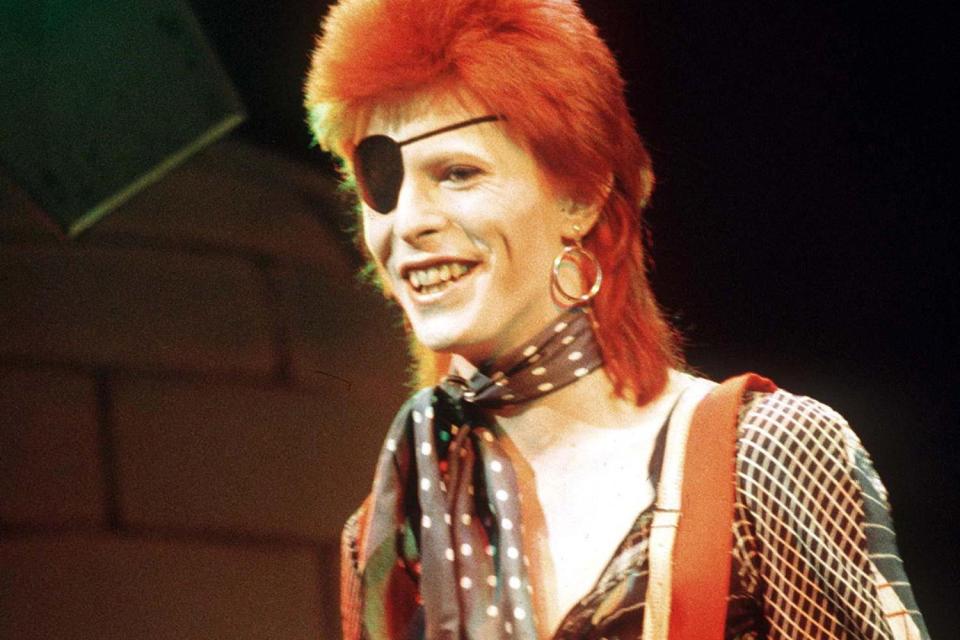

Thankfully, there’s also the music. Garson has assembled a band to perform Bowie’s 1973 album Aladdin Sane in its entirety, followed by some old favourites. The band, which turns out to be very good, is made up of people with connections to Bowie and Iggy Pop (and PJ Harvey) although the singer is a Guatemalan-American woman called Gaby Moreno, who has no discernible connection to Bowie. She is, by some distance, one of the youngest people in the room, where the average age is well into the 50s.

The band do a decent job of what is, essentially, a karaoke experience. It was always going to be weird spending an evening listening to Bowie songs without Bowie to sing them and it is, but not as weird as hearing 250 people bellowing the words of Drive-In Saturday and Prettiest Star at the top of their (mostly) throaty male voices while a bloke who was actually in the studio when Bowie recorded them plays the piano. I enjoy it, though the Bowie fans are divided.

As diehards they are, of course, bereft without their idol and therefore nothing will compensate for his loss; on the other hand, Garson worked with the great man and was a close friend, and he clearly misses him enormously: his voice trembles with emotion when he tells stories about their relationship. I too have mixed emotions. I love Aladdin Sane, which I remember buying as a small boy, and I have fond memories of time spent with Bowie, both as a fan and an interviewer, but I’m not sure I would have paid all that money to see a show without him.

I spend the gig squeezed against a wall at the very back, next to two Bowie-loving West Ham-supporting Cockney brothers called Keith and Ian. Keith, being barely five foot tall, can’t see a thing. At one stage he takes a photo of the back of the heads of the taller people in front of him and sends it to his wife “so she can see what I can see.” Like most of us, Keith first heard Bowie as a boy. He grew up up in the East End of London and remembers running into some mates on the streets of Hoxton in the early 1970s. “I was 15 and I was a hooligan,” says Keith, who is now 62 and presents a radio show.

One of the lads showed him a picture from a music paper of a pop singer with make-up and an orange feathercut who had just released a song called Starman. Keith was not immediately impressed. “I said: ‘What a f***ing poof,” he recalls. “But my mate, a guy called John Beverley” – soon to become better known as Sid Vicious – “said to me: ‘No, he’s alright.’ A bit later I was round a mate’s house and he played me the song Five Years on a tiny record player and as soon as I heard the drum beat, I was sold.”

The next day Keith sent his brother Ian down to the shops to buy a copy of Ziggy Stardust and the rest, as they say, is history. Between them the brothers have notched up around 160 Bowie concerts since then, following him all over land and sea (and Leicester) from 1973 onwards. But even their combined total cannot compete with a lady called Charlie, who is a legend among the Bowie fans.

I have to wait to talk to her afterwards because she’s right at the front for the gig, just as she has been for most of the 192 Bowie gigs she has attended in every corner of the world. She can even tell me the dates of each one (and does) and, according to Natasha, who first discovered Bowie as a child growing up in Africa from records that her older brother brought home from boarding school in England, the set lists.

What makes Charlie special is that, whereas Keith first saw Bowie in 1973, she didn’t see him until 1987, when even the staunchest Bowie fan would admit he was at his creative nadir, on the Glass Spider tour. She has made up for her late start by seeing virtually every single show he has done since then, everywhere in the world. Charlie is 46 and informs me, with very little prompting, that Bowie first played Aladdin Sane live on 4 June 1996 in Tokyo. It goes without saying that she was there. As she was in Hiroshima, where she tracked him down and he gave her a free ticket for the concert.

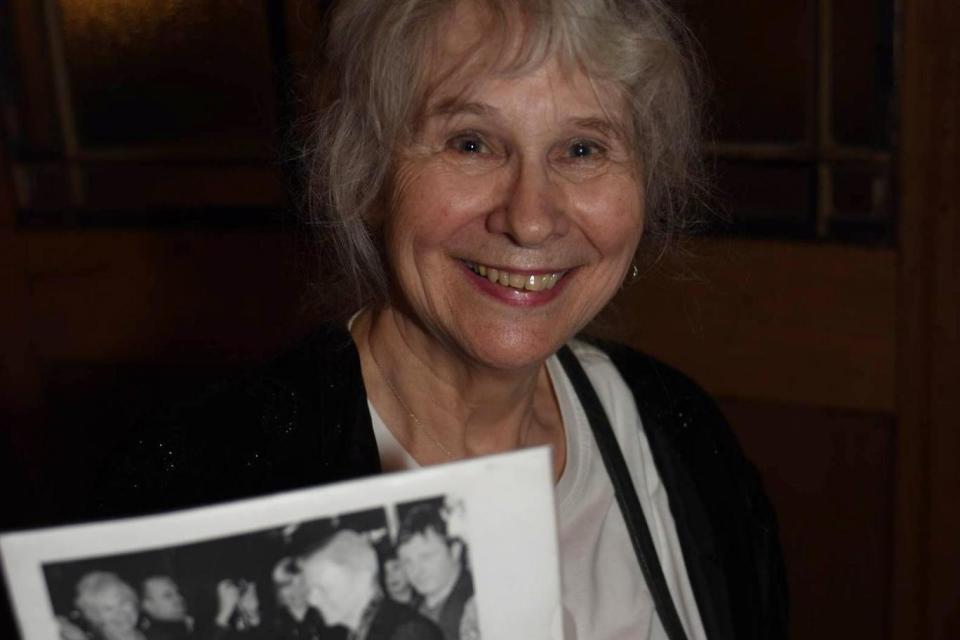

Then I meet Jenny, who is 73 and almost certainly the only person in the room who has never seen David Bowie live. In fact she had never heard of him until three or four years ago when she bought a DVD box set of a TV show called Life On Mars. “I thought it would look nice on top of the piano so it sat there for a year or so and then one day I decided to watch it,” she says. When the title song came on at the end she was struck by its beauty. “I dashed upstairs to google it and see who it was by.”

You may well wonder how Jenny had managed to avoid hearing of David Bowie until 2014 and the answer is that she worked in the opera and was married to a man who only listened to Radio 3. “I liked The Beatles when I was a girl,” she says, “but after that it was all Joan Sutherland.” Until she discovered Bowie. Before long she was catching up by buying his albums “in a record shop in Muswell Hill” and working her way through his repertoire chronologically.

Then she took a plane to New York to see the opening night of Lazarus, the theatre production on which Bowie collaborated just before his death. “I didn’t have a ticket but I went along anyway and just before it started he walked by – and someone took a photograph of both of us.” Jenny managed to get into the next three nights – inevitably she met Charlie there – and when the show moved to London she went again. “Sixteen times.”

The Bowie fans are a curious collection. They have little in common apart from their shared passion but that passion makes them like one big family, or congregation. Before the show starts I ask Chas to try to explain what first attracted him and what has kept him coming back for 40 years. Is it perhaps like falling in love, I ask. “It’s all about the music,” he insists. “I find the songs very personal. As if they were written for me. The music speaks to me. The lyrics are about my life.” He says his devotion has taken him to many “many nice places that I would never have been and I’ve met so many nice people”. He adds: “I’m not ashamed of it and I don’t regret any of it. If anything, I wish I’d seen him more often.”

Then the band comes onstage and Chas picks up his coat and heads for the exit. Aren’t you going in? I ask him. He shakes his head. “No point without David,” he says. “I just came to see my friends.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News