Moby: ‘I don’t want to know what strangers think about me’

‘I don’t want to know what strangers think about me’

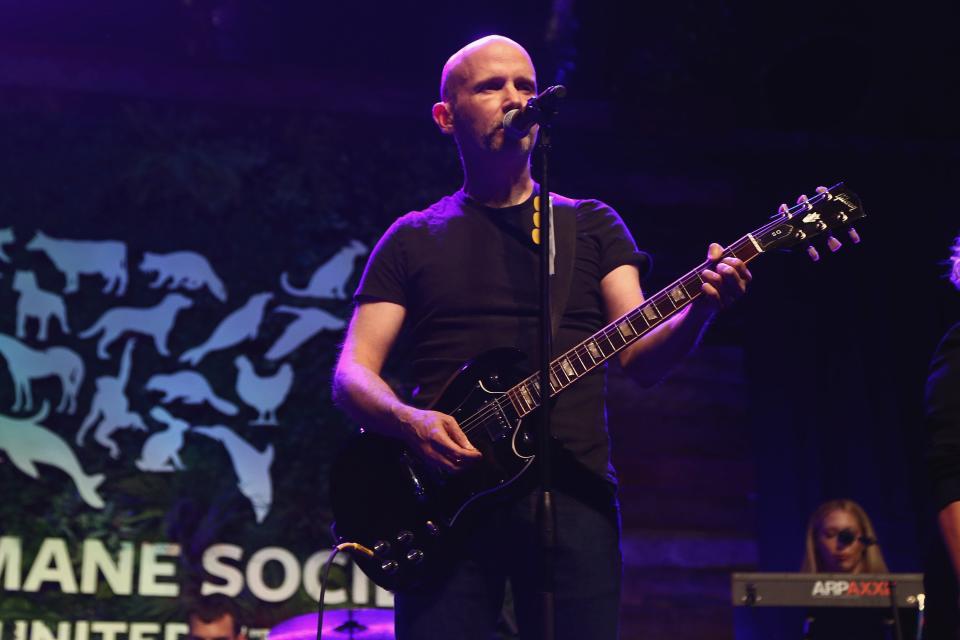

(Travis Schneider)Moby does not want to turn the Zoom camera on today. It’s not possible to see the loud tattoo shouting “VEGAN FOR LIFE” on the side of his neck or the “ANIMAL RIGHTS” he’s recently had inked down his arms. Or the Griffith Park-adjacent estate where he’s been holed up for the pandemic. Or the baldpate that’s synonymous with chillout electronica. You get the sense that, following two memoirs and now a biographical documentary, the only person Moby wants to judge him is himself.

“Basically, I don’t want to know what strangers think about me,” he says matter-of-factly. The musician, author and animal rights activist doesn’t read the negative press about him, at least he tries not to. “If anyone has an opinion about me and they share it in public, whether it’s on NPR, whether it’s a Washington Post op-ed, whether it’s a comment on social media, whether it’s a good article, whether it’s a slanderous article, I simply let everybody I know – and everybody I work with – I just make this one request: ‘Please don't tell me about anything, unless it’s really out of control.’”

And yet, the 55-year-old persists with the press cycle, which suggests either unwavering self-belief or elaborate self-sabotage. This time he’s promoting a “surrealist” documentary about his life (Moby Doc, dropping 28 May) and an accompanying album, Reprise, featuring orchestral and acoustic arrangements of songs spanning his 30-year career. Maybe he wants to set the record straight about a few things. Maybe, on some level, he just can’t help but keep touching the hot stove.

As for Moby Doc, which features cameos from David Lynch and bills itself as “a creative, offbeat, wry, music-filled chronicle of an eventful life examined”, the film definitely goes out of its way to be unconventional. Its subject stages therapy sessions and DIY dioramas as narration devices. Actors portray Moby’s mother and father, an alcoholic who died in a car accident when he was a toddler. The Twin Peaks director says nice things about him.

Instead of making “another biopic about a weird musician”, Moby narrates in the film’s introduction, let’s instead dig into “the why of everything”. Specifically, why do humans (Moby) try to fill emotional voids with superficialities like money, drugs and fame – which is what Moby spent a lot of the Nineties doing. An underprivileged childhood suffering from neglect, as Moby’s was in the unlikely wealthy suburb of Darien, Connecticut in the Eighties, looks to be one reason. “When I was growing up, I assumed that success as a musician was going to fix every psychological issue I had and was going to create unending, lasting happiness for me,” he says. “And then I found myself as a successful musician and my psychological issues, not surprisingly, had not been fixed. In fact, they sort of metastasised.”

Even though the documentary’s themes reek of narcissism – which even he admits in the film itself – he says that these interrogations have a broader purpose beyond exposing the dark side of celebrity. “Looking at my story [will hopefully] enable people to relate to their own lives and to look at this assumption that we all make: external things will fix our internal issues. Look, most likely that's not ever going to happen. If external things fixed internal issues, Kanye West and Donald Trump would be the happiest people on the planet.”

Likewise, Reprise, recorded with the Budapest Art Orchestra, sees the rave pioneer revamp three decades’ worth of musical highlights. The still-remarkable “Porcelain” gets a gentle redux featuring My Morning Jacket’s Jim James. “Go” is made more bombastic, replete with thunderous drumming and screeching synths. Additional guests include Tennessee singer-songwriter Amythyst Kiah, gospel singer Deitrick Haddon, soul legend Gregory Porter and Kris “A Star Is Born” Kristofferson. It’s a shame that Moby’s public persona all but eclipses his artistry; he clearly still has an endless imagination for sonic texture and melody.

As a young adult living in an unsanctioned factory space in Stamford, Connecticut, Moby got his start performing in local punk bands before transitioning to electronic music. In the Eighties, he spun records at indie radio stations in New York City, which eventually led to DJing gigs in clubs. His breakthrough was 1991 single “Go”, a moody dance single that sampled Angelo Badalamenti’s “Laura Palmer's Theme”, from the then-new hypnagogic crime drama Twin Peaks. Between 1992 and 1999, Moby released five records, the most successful of which was undoubtedly 1999’s Play, which featured the then-ubiquitous “Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad?” and sold more than 12 million records worldwide.

Much later, he released a successful rock memoir, 2016’s Porcelain, that detailed his growing up years in the Seventies, achieving pop stardom, his internal struggles with religion and recreational drug use, and his interest in animal rights and veganism. His attempt to release a follow-up, 2019’s And Then it Fell Apart, was less fortunate – Moby’s attempts to describe his relationships with women came off as, to use actor Natalie Portman’s word, “creepy”. It ended with him cancelling his book tour and announcing that he would be retreating from the public eye.

Moby’s recollection of a brief romance with then-20-year-old Portman (13 years his junior) was one of the most talked-about passages in the memoir. The actor publicly disputed Moby’s account of events, telling Harper’s Bazaar: “I was surprised to hear that he characterised the very short time that I knew him as dating because my recollection is a much older man being creepy with me when I had just graduated high school.”

She continued, alleging that she had not been 20, but 18: “I was a teenager. I had just turned 18. There was no fact checking from him or his publisher – it almost feels deliberate… That he used this story to sell his book was very disturbing to me. It wasn’t the case. There are many factual errors and inventions. I would have liked him or his publisher to reach out to fact check.”

At the time, Moby reiterated his claims, posting a picture of the two of them in 1999 to Instagram, with a comment that her account “confused me, as we did, in fact, date. And after briefly dating in 1999 we remained friends for years. I like Natalie, and I respect her intelligence and activism. But, to be honest, I can’t figure out why she would actively misrepresent the truth about our (albeit brief) involvement.”

His defensive response did not go down well, especially against the backdrop of the mounting #MeToo movement. The press leaped on the story (“Moby wrote about sleeping with Natalie Portman because Moby thought that sleeping with Natalie Portman made him cool,” wrote Rolling Stone). Later, he followed it up with a post titled “From Moby, An Apology” in which he wrote: “As some time has passed I’ve realised that many of the criticisms levelled at me regarding my inclusion of Natalie in Then it Fell Apart are very valid. I also fully recognise that it was truly inconsiderate of me to not let her know about her inclusion in the book beforehand, and equally inconsiderate for me to not fully respect her reaction.”

His self-imposed hiatus didn’t last long. Is releasing a documentary about himself an attempt at making amends? If the answer is yes, Moby doesn’t exactly say so. Instead, he doubles down on how both his memoirs (the first, 2016’s Porcelain) and the documentary “are very clear documents of a lot of mistakes, a lot of naive mistakes, a lot of very clumsy mistakes”. And similar to And Then it Fell Apart, Moby again adopts that same wide-eyed “who, me?” outsider perspective as he recounts what it was like to sell millions of copies of records, get rich and “go to parties and women I'd never met would flirt with me”, as he recounts in the film.

[Fame] ultimately completely corrupted and ruined me, but at the time it was so much fun

Moby

The film does not mention Portman or the fallout from his book. It only appears to continue the Moby myth of the tortured genius, coming to terms with himself. Talking on the phone in an Indian grocery, Moby says in the documentary: “It ultimately completely corrupted and ruined me, but at the time it was so much fun, to go from being kind of a washed-up has-been to dating movie stars and going to these parties and making a lot of money and touring and playing in front of tens of thousands of people. Maybe I should pretend it wasn’t great, but for a minute, it was really, really great.”

He doesn’t say explicitly whether he’s learned anything from the experience and instead says my question about whether or not he’s learned anything from the Portman pushback just “ties perfectly back to what we were talking about earlier. Which is, my emotional state and sense of self shouldn't be informed by the opinions, especially if they involve being attacked by strangers.”

“It’s certainly not pleasant when you have TMZ and other people camped out in front of your house, you know, screaming at you and trying to get you to say something that will incriminate you,” he adds.

This refusal to engage with people’s opinions of him also extends to social media. And yet, Moby does post quite regularly to platforms such as Twitter and Instagram. He even recently started a TikTok, where he posts remixes of his most well-known tracks. One has to ask: why keep putting yourself out there, if the ostensible purpose of social media – for artists, that is – is to engage with fans? This contradiction seems to escape Moby, who cites his being an “absolutist” in regards to not reading bad press or comments. This also applies to drinking, which he says he hasn’t done in 13 years. “I have to 100 per cent say no to drinking and drugs largely because it’s easier. I don’t envy these people who aren’t sure. That ambiguity, you know, that would be so confusing to me. [I do] the same thing with veganism.”

If anything, Moby’s clarion call around veganism has only intensified over the years. He was an early adopter, for which he was routinely mocked – though, of course, veganism is now as common as gluten-free pizza. But Moby is rather like the straight-edge guy at punk shows, who really, really wants you to know he’s vegan. He always goes one step further, hence those alarmingly large new tattoos. “I'm fully aware of the fact that a guy in his fifties deciding to suddenly get facial and neck tattoos... it's a little bit odd,” he admits. “But there’s nothing in my life that’s more important to me than working on behalf of animal rights. This is more important to me than dating. This is more important to me than a career. This is more important to me than health.

“If I’m being honest,” he continues, “There is a rejection aspect of it. By doing this, I’m rejecting caution. I’m rejecting conventional ideas of beauty. I’m rejecting being timid about my beliefs. I’m saying, ‘No, it’s the world that can’t handle it. If the world takes issue with my desire to protect innocent beings and climate change and protect human health and protect workers and reduce antibiotic resistance, if people have an issue with that, that's their problem. Not mine.’”

It doesn’t exactly help his cause that Moby faced some issues with his own vegan venture, Little Pine, last year. Towards the beginning of the pandemic, the LA restaurant – which was originally founded as a philanthropic venture, with 100 per cent of its profits going to animal-related causes – went on a permanent hiatus, abruptly terminating the employment of its 50-member staff. Angered by the sudden turn of events, former Little Pine workers took to social media, accusing Moby of leaving them “high and dry”, with no sick pay or health insurance. “Not all people who love to have a philanthropic reputation are, in fact, good people,” wrote one former employee, who later claimed to have been blocked by Moby.

“I know this is really selfish,” he admits, “[but] everything that was going on at that time was so unprecedented. Friends of mine were dying. Food supplies were going to be shut down. We didn't know if the pandemic was going to last for 15 years and represent the end of civilisation. And in the middle of that, I was tasked with trying to shut down my restaurant. And I had never shut down a restaurant before. I barely knew how to run a restaurant. So I did the best that I possibly could. I lost a couple of hundred thousand dollars just shutting down the restaurant. And considering I had run the restaurant as a nonprofit… I'd never taken a penny from it.”

Little Pine has since reopened under new management. And Moby is a little hurt about his former staff. “I will never complain about how I was treated [on social media],” he concludes. “But it was a little disconcerting to find out that the people I had been taking care of and giving salaries to for four years didn't come to me. The fact that it escalated from zero to viciousness with nothing in between – like, no one reached out to me to talk about it. It was just all of a sudden, I was crucified.”

Given everything – the music that made him a household name, the business ventures, his amplified commitment to animal rights, the scorched-earth press – Moby still feels he has a lot left to give, creatively speaking. Animal rights might be his number one priority, as he reiterates repeatedly, but music ranks as a close second. “What's happened over time is, I don't even really see music as a career,” he says. “Music is what I love. And I guess technically it's my job because it helped me pay the rent. But the joy that I get from just simply making music and the act of releasing it... the idea is to create something beautiful that you love and put it out into the world and hope that someone has an emotional connection to it.”

And if audiences continue to distance themselves? “If my being a punching bag in any way compromises my ability to help animals, that's when I start crying myself to sleep,” he says.

As our time runs out, Moby reminds me that if I ever take a walk in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park, I should consider the black beetle, aka the animal he likens himself to the most. “A few years ago, I was at this event, and the question was, what's your spirit animal? And my friends, understandably, picked cool animals. Like a wolf or a falcon or a dolphin. And I picked that little black beetle in Griffith Park. Every time you see them, they’re stumbling along. There’s nothing glamorous or attractive about them. If you put a giant piece of wood in front of them, they go over it or they go around it, they keep stumbling along. One of my only strengths is, no matter what happens, I stumble. I just keep stumbling along.”

Moby’s Reprise is out via Decca/Deutsche Grammophon on 28 May, accompanied by a documentary that will be released digitally

Read More

It’s #AmapianoSeason: why South Africa’s house spin-off will be the sound of summer

Bob Dylan’s 20 greatest albums, from Blood on the Tracks to Rough and Rowdy Ways

Billie Marten: ‘Most people I know with a top 10 album are on Universal Credit’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News