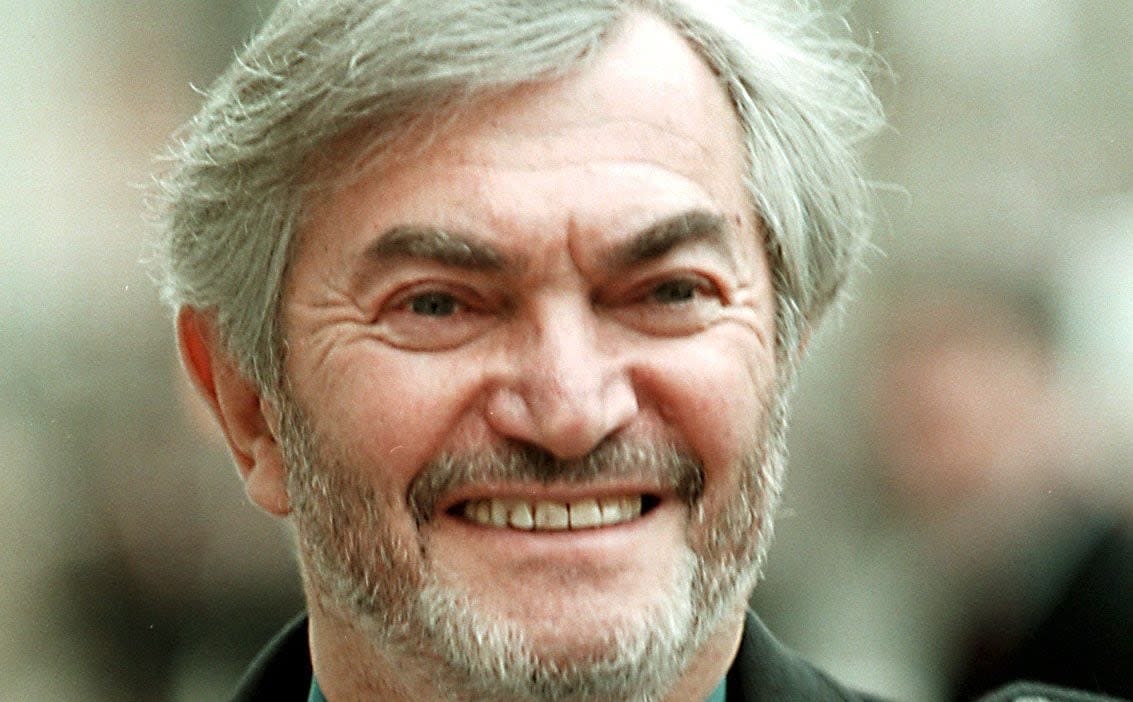

Monty Norman, composer who wrote the celebrated James Bond theme tune and won a court case over its authorship – obituary

Monty Norman, who has died aged 94, was the composer of the sinister James Bond theme; it was originally written for Dr No, the first film in the famous franchise based on Ian Fleming’s books, but Norman had to fight through the courts to uphold his ownership of the music.

Norman had already worked on five stage musicals when Cubby Broccoli invited him to join the Bond team. Broccoli had been one of the financial backers of Belle, a show by Norman that had not fared well. Nevertheless, Broccoli had been impressed by the music and he and Harry Saltzman, the producer, invited Norman for a chat at their Mayfair office.

“He said they had just acquired the rights to Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels and were going to turn them into films,” recalled Norman. “The first one was going to be Dr No and would I like to do the score?” As Norman was leaving that meeting an assistant muttered to him: “See if you can get a good theme for this, because I reckon we’ve got two films and a television series in this.”

At first Norman was reluctant because he was working on two other stage shows. But he was persuaded when Broccoli offered him and his family a three-week visit to Jamaica, all expenses paid, during filming. “That was the clincher for me,” he said. “I thought, even if Dr No turns out to be a stinker at least we’d have sun, sea and sand to show for it.”

The crew flew out on a chartered flight in January 1962, where they met the cast, including a little-known Sean Connery and the Swiss actress Ursula Andress. The sinister Bond theme emerged from a number called Bad Sign, Good Sign that Norman had written for A House for Mr Biswas, a musical set in the Indian community in Trinidad that never saw the light of day.

With a little rewriting, what had started out as “a little Indian-type song”, as Norman called it, evolved into the famous tune. “From the moment I did that I knew I had the James Bond theme,” he said. “I wanted the character, the mystery, the atmosphere, and it was all there.”

It was not the only music he wrote for Dr No. Underneath the Mango Tree is heard when Ursula Andress, playing Honey Ryder, the first Bond girl, emerges sylph-like from the sea and is startled to encounter Connery’s Bond. “Someone told me that ‘making love’ was ‘make boolooloops’, which I’ve never heard since, but it worked for the song,” he recalled of its famous lyric.

His then wife Diana Coupland dubbed Ursula Andress’s singing voice for the song. Other numbers he wrote for the film included The Kingston Calypso, a Caribbean take on Three Blind Mice, to accompany the opening scene with three blind assassins, and Jump Up Jamaica, which became a hit on the island.

Things began to turn sour when Melody Maker suggested that Norman had bought the James Bond theme from a Jamaican musician for $100. “I was told this was libel and that I should do something about it,” he said. “But my feeling was that I should try and find this ‘old Jamaican’ and get him to write a few more for me and I’d give him another hundred.”

To confuse matters the producers, who by some accounts were not happy with Norman’s orchestrations, engaged John Barry (who died in 2011) to rearrange the score. Over the years Barry, who wrote music for the subsequent Bond films, became increasingly associated with the famous Bond theme to the point that Norman’s role was increasingly being forgotten.

In 2001 The Sunday Times published an article under the headline “Theme tune wrangle as 007 shaken and stirred”, which alleged that Norman did not write the theme. He sued the newspaper for libel. The High Court case involved a bizarre moment in which Diana Coupland, by then Norman’s ex-wife, was cross-examined about a visit that Barry had made to their flat when the theme was played.

Asked how she knew that Norman played it to Barry, rather than the other way around, Coupland replied; “Monty is the worst pianist in the whole world – I couldn’t mistake that for anything.” Norman won the case and was awarded damages of £30,000 plus costs in excess of £500,000. As he later said: “There’s an old saying in showbiz: nobody argues over a flop.”

He was born Monty Noserovitch in Stepney, East London, on April 4 1928, the night before Passover. He was the only child of Abraham, a cabinet maker who had fled Latvia as a child, and his wife Annie (née Berlin), who spent hours on her sewing machine making girls’ dresses to be sold in East End markets.

He recalled his parents moving out of his grandparents’ home and into their own rented rooms, where the landlady’s son let him play his guitar. “I can still remember the thrill of the moment,” he said of the first time he held the instrument.

During the war he was evacuated from London, but returned at the height of the Blitz. He was 16 when his mother bought him a 1930s Gibson guitar, which he kept for the rest of his life “as a talisman”. His parents could not comprehend his interest in music, “but bless ’em, they were wonderful and just let me get on with it,” he said.

The family moved to St Alban’s, in Hertfordshire, where he joined the Army cadets. “We used to put on concerts and I suddenly realised I had a voice,” he said. Soon he was having guitar lessons with Bert Weedon, who became a star in the 1950s and 1960s and once told him: “As a guitarist you’ll make a great singer.”

Weedon helped him to find a singing teacher, Laurence Leonard, who wanted Norman to go into light opera, “but I had already started doing gigs with young up-and-coming jazz musicians”, said Norman. Soon he was making radio shows and before long was invited to join Cyril Stapleton’s band as a singer.

He appeared at the London Palladium with the Ted Heath Orchestra, took part in a series of variety shows with Benny Hill, sang with the Goons and performed with Tony Hancock and Tommy Cooper. But during the 1950s his interest was turning to writing songs rather than singing them. He wrote False Hearted Lover and when it became an international hit he gave up singing altogether. “My parents had misgivings, but I was certain that was what I wanted to do,” he said.

Irma La Douce, the first West End musical he worked on, was a triumph, running for five and a half years and receiving seven Tony award nominations. It was followed by Expresso Bongo, which starred Millicent Martin and Paul Scofield and led to the 1959 film starring Cliff Richard. Make Me an Offer, set among the antique dealers of Portobello Road, won the Evening Standard award for best musical in 1959.

There was frustration when a musical based on A House for Mr Biswas, by VS Naipaul, and directed by Peter Brook, was shelved after Norman had spent two years working on it. However, he then turned his attention to Belle, about the murderer Dr Crippen.

He and Wolf Mankowitz, the producer, raised the finance by staging a Sunday-afternoon audition and inviting potential backers. Among them was Broccoli, who invested heavily, but the show closed after only six weeks. Norman later blamed the dark subject matter, saying that it had been ahead of its time.

While Norman was working on Dr No in Jamaica he met Count Basie. “He asked me to send any numbers from Dr No that might be possible for his orchestra,” Norman recalled. Basie later recorded four of them. Afterwards he was asked by Saltzman to work on Call Me Bwana (1963), starring Bob Hope. Yet he was unable to get a written contract and when he finally cornered Salzman the producer told him: “Monty, if you wanna talk money, we can’t do business.” Norman eventually received the Hope contract, but recalled: “I didn’t get any Bond films after that.”

He continued writing musicals, though nothing came close to matching the success of his Bond theme. Stand and Deliver, written with Mankowitz and which opened at the Roundhouse in 1972, was “a feeble imitation of The Beggar’s Opera”, according to the critic Irving Wardle, who added that it had been “knocked up … on the debatable assumption that paying audiences are more interested in sex than economics”. It lasted 14 performances. However Poppy (1982), a pantomime-style production set in the first opium war, ran for over a year and picked up an Olivier award.

There were also television themes, including Dickens of London, Who is Sylvia? and The Battersea Miracle. In 1989 the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors awarded Norman its gold badge of merit; he also received a special Ivor Novello award in recognition of his work on the Bond theme.

Norman spent many years writing his autobiography, A Walking Stick Full of Bagels, though it was never published. In the late 1950s he married Diana Coupland, the singer and actress who starred in the 1970s sitcom Bless This House; they had a daughter. That was dissolved in 1980 and he married secondly Rina Caesari.

Monty Norman, born April 4 1928, died July 11 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News