Pistol, Midas Man, Elvis, Going Electric: how the classic rock canon is being rebooted

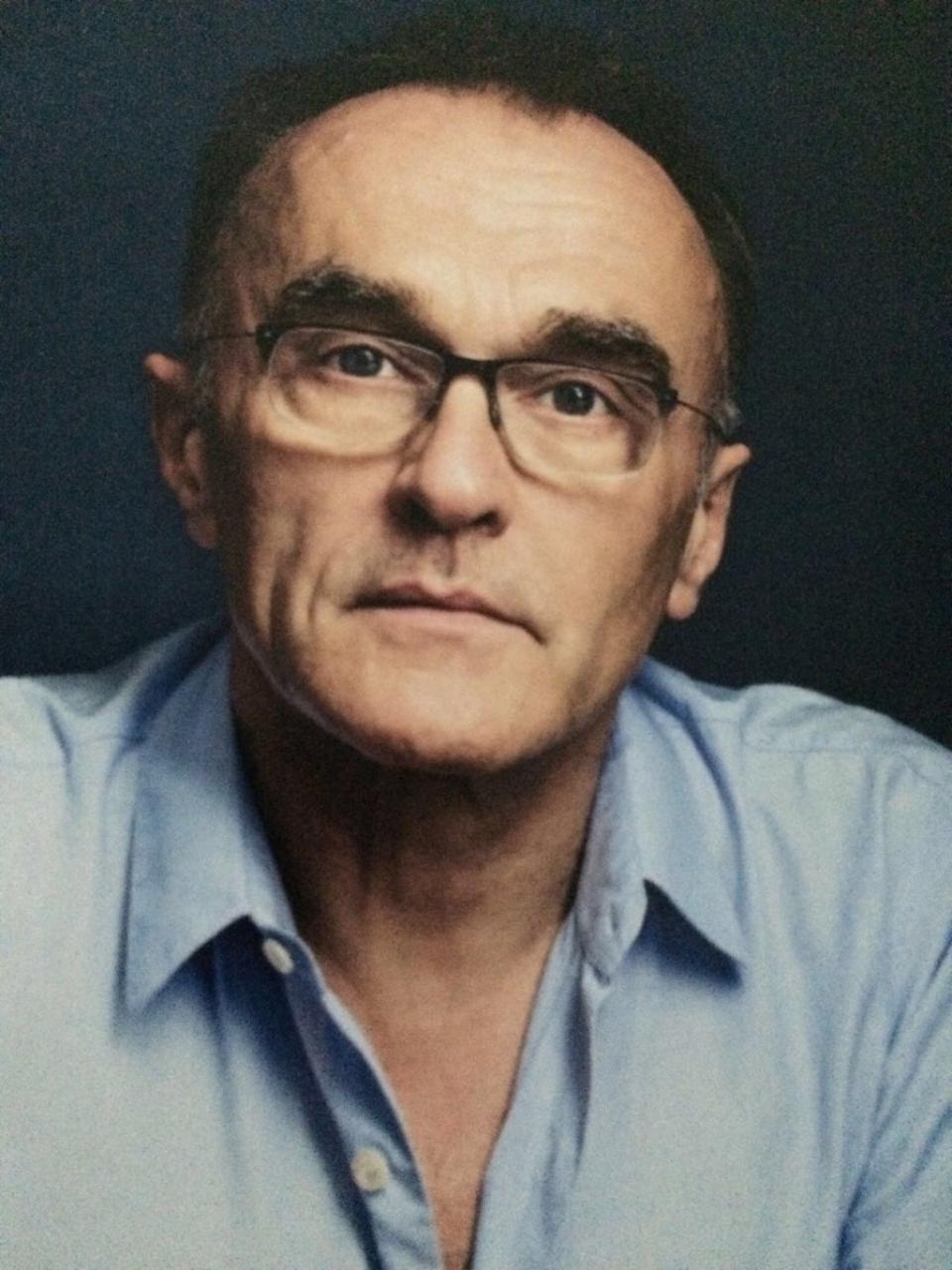

It’s a big year for the classic rock canon. This month will see Danny Boyle’s series Pistol, about the rise and acrid, public fall of the Sex Pistols, land on Disney+. The filth and the fury, as the front page of the Daily Mirror put it in 1976, will sit next to Toy Story, Captain America and the 1986 ET knock-off Fuzzbucket on the home of Mickey Mouse.

They’re not the only heritage act getting a glossy retelling of their story in 2022. Later in May there’s Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, starring Austin Butler as Presley and Tom Hanks as the singer’s manager Colonel Tom Parker. Midas Man, a biopic of the Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, is slated for this year too, and there are more in the pipeline.

Timothée Chalamet spent some time in the pandemic’s first summer bouncing around Greenwich Village and Woodstock with a copy of Bob Dylan’s memoirs in hand, in preparation for playing him in the much-delayed biopic Going Electric. Kiss, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, the Grateful Dead and Joey Ramone are all reportedly getting the biopic treatment.

But what can the Sex Pistols mean to a generation which is as likely to know John Lydon as Johnny Rotten as they are to know him as the guy from the butter adverts? And why are they and their Mojo-approved brethren suddenly being snapped up for massive, splashy, awards-bothering biopics?

It’s partly down to money. Traditionally, the way that labels introduced heritage acts to new generations was with new formats: the junctures when cassettes replaced vinyl, CDs replaced tapes and streaming replaced CDs all gave an excuse for a gigantic marketing push. It was a win-win for labels: they didn’t need to get any new music or spend time building up an act’s profile; they just put classic albums on a new, usually more expensive technology and started putting the champagne on ice.

It’s only a tiny sliver of people who still buy music these days, though. So how does a label or manager sweat an asset like a heritage act when your act can’t tour anymore because they’ve split up or died, and when you can’t rely on the existing fans buying everything all over again? A biopic. It’s the go-to way to get younger people into your act while reminding the fans who remember them the first time around why they’re so great.

Making an ageing (or dead) star look young and sexy and fresh all over again – look, Elton John isn’t in his seventies; he’s Taron Egerton! – is a reliable booster for streaming numbers. The Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody fuelled a massive spike in Queen streams in the last quarter of 2018 – no artist had more songs in the top 200 most streamed charts, and 70 percent of all Queen’s streams came from fans under 35.

Post-Rocketman, John’s stock has rarely been higher. In 2021 his collaborations with Ed Sheeran and Dua Lipa got him two number one singles, the first time he’d had two top 10s in a calendar year since 2002.

But there’s something else happening here too, and a quote Boyle gave about Pistol points to why we’re seeing so many biopics just now.

“It is the detonation point for British street culture,” he said in a statement when the series was announced, “where ordinary young people had the stage and vented their fury and their fashion… and everyone had to watch and listen.”

That makes it sound a lot like Pistol will reframe the band’s nihilism and abrasiveness as just part of punk’s productive, creative, egalitarian revolution. They’re not just the dumb mutiny of Sid Vicious slashing himself with a broken bottle; they’re the embodiment of rebellion and individual expression, with a cynicism towards plasticky corporate culture and unthinkingly accepting class strictures.

It’s less no future for you, and more England’s dreaming. Suddenly the Sex Pistols feel a lot less timelocked as a phenomenon.

That Pistol is on Disney+ rather than any other streaming service fits too. Having enjoyed a massive hit with The Beatles: Get Back, the immersive fly-on-the-wall documentary which made the most familiar and ubiquitous of all the classic rock acts feel miraculous all over again, Disney has found a subgenre that fits the profile of its platform.

According to Nielsen, the audience of Disney+ skews younger – as of last summer 23 percent of all streaming service users were over 55, but only nine percent of Disney+ users were in that bracket. It’s exactly that younger base that Pistol, Elvis and Midas Man will try to tap into.

Correcting long-standing omissions from bands’ and movements’ narratives are another way in. Aside from Vivienne Westwood, women have rarely been given much of a role in the story of punk. But in Pistol Maisie Williams will play model and actor Pamela Rooke, and Chrissie Hynde, Siouxsie Sioux and Soo Catwoman will pop up too.

Judging by its trailer, Luhrmann’s Elvis will try to do something similar. In America, rumours that Presley was racist and had said in an interview that black people were only fit to “buy my records and shine my shoes” spread through the 1950s, despite being untrue. The idea that Presley became enormously wealthy and successful by taking rock ‘n’ roll, built by the innovations of black musicians and producers, and making it more palatable to a white audience persisted too.

In 1989, Chuck D of Public Enemy distilled the suspicions about Presley bluntly in Fight the Power: “Elvis was a hero to most, but he never meant shit to me you see – straight up racist that sucker was, simple and plain”.

Elvis will implicitly rebuke all of that. We’ll see a young Presley sneaking into a black church service and discovering the power of music, plus there’s the suggestion that Presley was unhappy not to be allowed to speak about the death of Martin Luther King and a black character points out that “they might put me in jail for walking across the street, but you’re a famous white boy”.

In entwining the King’s music and life with the black communities he lived alongside growing up in Tupelo, Mississippi, and emphasising his connection to King – Presley cried while watching footage of King’s funeral, and insisted he close his 1968 comeback TV special with the King-inspired song ‘If I Can Dream’ rather than ‘I’ll be Home for Christmas’ – while acknowledging Presley’s debt to black artists, Elvis will try to reorientate him as a sincere advocate of civil rights.

Meanwhile Rocketman showed John having fun, sensual, joyful sex with his then-manager John Reid, while Bohemian Rhapsody was oddly coy about Freddie Mercury’s sexuality. A short scene where Mercury heads into a toilet with a man for, presumably, casual sex, made the queer bits of Mercury’s life look grubby and furtive where Rocketman was celebratory.

What all this means is that it isn’t enough anymore to just tell the story of an artist’s life, get some critical buzz with an uncannily good central performance, and wait for the streams to roll in.

Now, a biopic has to set the ideological lens through which an artist comes into focus: Presley becomes politically conscious in a serious, empathetic way; Elton John found happiness embracing his sexuality; the Sex Pistols showed young people what power they had (quite how Kiss are intending to go about it is anyone’s guess. The story of one plucky band-stroke-multinational-licensing-machine’s fight for the right to open a Kiss-themed minigolf course in Las Vegas might be a tricky sell).

There’s a profound shift happening here. The biopics that work renew as they commemorate. Rebooting a heritage act is more likely to stick if you can convince newcomers not just that an artist is really good, but that the artist fits their worldview and means something beyond themselves.

What we’re seeing is the process of the baby boomers’ musical heroes being gently prised out of their hands and handed down to Gen Z, along with a new set of stories which make them resonate all over again on an emotional level.

It’s far easier to imagine yourself in a Britain where young people yearn to smash apart a system that doesn’t serve them, as in Pistol, than to hear another set of talking heads going on about a Britain with three TV channels and still pock-marked with bomb sites from the Second World War.

Stop your cheap comment, as Rotten once sang. We know what we feel.

Pistol is on Disney+ from May 31

Yahoo News

Yahoo News