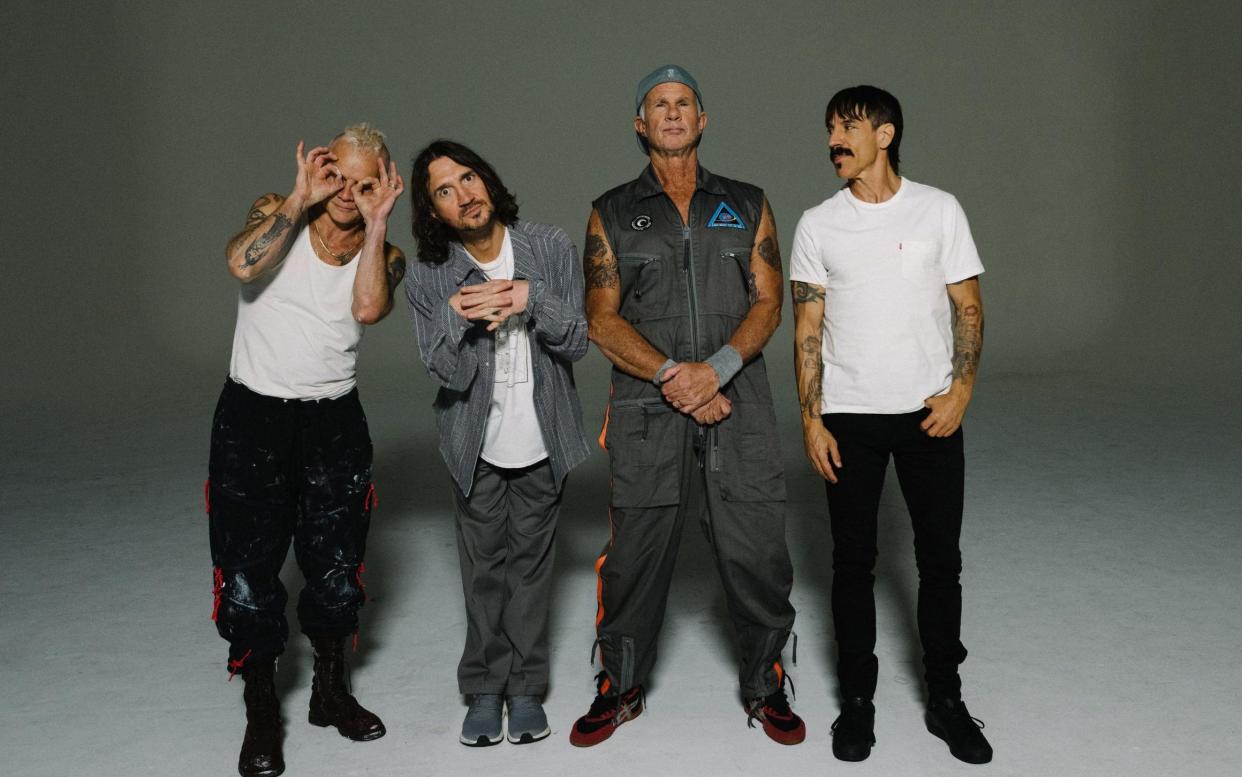

Red Hot Chili Peppers come back lean and clean, plus this week’s best albums

Red Hot Chili Peppers, Unlimited Love, ★★★★☆

The slick Californian quartet return with their 12th album, which sounds exactly as you might expect with super inventive guitarist John Frusciante back in the saddle for his first album with the band in 16 years, and super producer Rick Rubin back behind the controls. Unlimited Love features 17 tracks and clocks in at 73 minutes of the Chili Peppers doing their Red Hot thing.

The sound is lean and clean, sharply separated with individual instrumentation shining through and not a lot of over-dubbing or effects. The Peppers are an utterly distinctive band who just seem to enjoy playing together. Which is fair enough when you have musicians of this calibre and character, certainly amongst the finest and most distinctive in the modern rock pantheon.

Drummer Chad Smith locks onto funky, propulsive grooves with dexterously nimble bassist Flea, whilst Frusciante fleshes out arrangements with an astonishing palette of chords and licks, the ensemble mashing up a vast array of influences from jazz, funk, hip hop, folk, psychedelic rock, punk, heavy metal and sunshine Sixties pop. At the fore is vocalist Anthony Kiedis, who makes the most of a limited range with a distinctive tone that always floats above the Chili jamming, a swinging sense of rhythm and fantastic facility for flowing, catchy melodies.

He is also, for better or worse, the most bizarrely impenetrable of lyricists, with an odd gift for stringing together baffling non sequiturs as if they might actually yield some meaning if he just delivers them with commitment. The aching choruses of opening track Black Summer suggest it could be a pandemic anthem (“It’s been a long time since I made a new friend / Waiting on another black summer to end”) but sense collapses under verses such as “Platypus are few / The secret life of roo / A personality I never knew, get it on / My Greta weighs a ton / The archers on the run / And no one stands alone behind the sun.”

Poster Child slams together pop cultural references without any tangible intent other than scansion (“Dave Mushegain Copenhagen / Cowboy ghost of Ronald Reagan / Dollar save was Flavor-Flavin’ / Cosmic rays of Carl Sagan”). I was relieved to read a lyric sheet to the priapic She’s A Lover and discover that he was repeatedly boasting “I will be a torrid beast” and not (as I first heard) “I will be a Tory beast” but I am no closer to uncovering the point of a song that includes the declaration “Any other day and I would say / You are Atlantis manta ray”. The fantastic jazz trumpet scatting through Aquatic Mouth Beast makes more sense than Keidis’s stoned ramblings (“I don’t know if / The embers of my burning flame / Are from this spliff / The greatest gift, the greatest gift”).

Apparently, the band went into sessions for this album with 100 songs, recorded 50, then chopped it down to a double album’s worth, but somehow Unlimited Love still sounds like it could benefit from ruthless editorial pruning. Presumably some fans find all this a delight but Kiedis’s endless fount of nonsense risks turning the Red Hot Chili Peppers best efforts into so much musical logorrhea. Neil McCormick

Walt Disco, Unlearning, ★★★★★

Back in the late 1970s, the new-romantic movement was born in influential London and Birmingham clubs like Billy’s and the Blitz. It was collision of music and fashion that embraced the flamboyance of glam-rock heroes such as David Bowie and Marc Bolan. Heralding its theatrical blend of synth-infused dance/rock beats was a legion of male and female punters dressed in frilly, gender-fluid garb and make-up worthy of a drag queen. It was a direct cultural response to the rampant poverty and political darkness of the times – not to mention the resultant explosion of punk. Fast forward to 2022 and the traumatic fall-out of Covid, Brexit, even more poverty, and the very real possibilities of a third world war, it’s clearly time for relief once more. Enter Walt Disco.

The good news is that the deliciously adventurous debut, Unlearning, shows the Glasgow six-piece band doing more than simply reviving a beloved era. They have boldly reimagined new-romanticism for the modern age, addressing the state of current life and times through a queer-centric lens. From the powerful synths of the album opener, Weightless, the band introduces an alternate universe that is, by turns, rife with elements of frenetic disco and operatic rock. That track’s refrain of “For all of my life I was in the dark… It's not too late to start” reveals optimism that prevails throughout even the most somber of Unlearning’s songs.

At the centre of the band is vocalist James Potter, who romps through every song with Shakespearean flair, effectively channeling the vocal vibrato of Bowie, while also tapping into the undeniable influence of ‘80s legends Billy Mackenzie of the Associates and Visage frontman Steve Strange. Potter raises the stakes of each track by punching nearly every lyric with extraordinary intensity. Even when Potter explores the softer tones of their voice, as they do on the swirling, Chic-flavoured Be An Actor, they are a commanding, enormously confident presence. Potter is in control of their own performance at all times, knowing precisely how to guide the listener to the emotional core of each song.

The rest of the band matches Potter with arrangements that are stacked with layer upon layer of instrumentation and samples that risk overwhelming the songs, but never push them over that line. Instead, they exhilarate and seduce the listener into a world that makes enduring and acknowledging turbulent times a bit more glamorous. Larry Flick

Dave Douglas, Secular Psalms, ★★★★★

Nobody in jazz has a more restlessly enquiring mind than trumpeter and composer Dave Douglas. He’s been voted best trumpeter more than once in Downbeat polls – the jazz world’s equivalent of the Oscars – and he can swing a jazz standard as hard as any. But he prefers to keep on the move, exploring new territory with each tour and album, often with a new set of collaborators and a fresh exotic set of sound-sources. As a result, each album is as much an elaboration of an expressive world as it is a set of jazz “numbers”.

The latest album is his most unlikely exploration yet. It was prompted by a commission to Douglas from the Handelsbeurs concert hall in Ghent for a new piece to mark the 600th anniversary of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb by Jan and Hubert van Eyck. This is a huge, many-panelled meditation on the mysteries of the Christian faith in a chapel in St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, which staggers the onlooker with its beauty and complexity. Douglas tells us he tried to capture the movement from the dark and mysterious interiors of the outer panels to the mystical garden in the central panel. Here, everything is bathed in sunshine (or perhaps the light of Heaven), and prophets and potentates are gathered to adore the Lamb of God.

In this 11-movement suite, Douglas has seized on the clues provided in the panels depicting angelic musicians, where we see singers, bowed and plucked instruments and an organ. We hear those sounds played by the sextet of young, mostly Belgian jazz musicians, alongside other musical signs of the early 15th century. The great composer Guillaume Dufay sprang from the same rich Burgundian culture that gave us this altarpiece, and Douglas tells in the liner notes that he learned from him. The angular intricacy of Dufay’s music, hinting at the arcane mathematical procedures behind it, infuses several numbers on the album, as does his suave lyricism.

One number, Hermit and Pilgrims, actually begins with the so-called “Burgundian Cadence” which even to the untrained ear immediately connotes the medieval era. Even more overtly medieval is the Agnus Dei, one of several numbers based on Latin or old French texts in translation. Douglas himself and serpent-player Berlinde Derman sing in two-part counterpoint, while Tomeka Reid’s cello anchors everything with a slower moving line, just like the “cantus firmus” in a Renaissance-era mass setting. Eventually, the piano joins in with a startlingly rapid counterpoint, more jazz-like than medieval in sound but faithful to the 15th-century idea that music could unfold in layers all moving at different speeds. Making this album would have been a hugely complex undertaking at the best of times, but no sooner had work begun than the pandemic struck.

As a result, each musician had to be recorded separately in the summer of 2021 in studios in Ghent, Amsterdam and Chicago, and the results stitched together. The results of this sort of patchwork can often be depressingly stiff and artificial, but the astonishing thing is how easy and spontaneous this album sounds. The vaguely medieval-sounding mixture of tuba, wheezing pump organ and lute is liable to be invaded without warning by Douglas’s nocturnal muted trumpet or Marta Warelis’s superbly to-the-point piano riffs, and yet it all blends into something coherent and utterly distinctive. And whenever the medieval fixity threatens to become monotonous, Douglas sets the harmony flying in a very un-medieval way. A piece inspired by one of the greatest sacred artworks ever could have been hamstrung by a sense of pious homage. In fact, it’s a delight. Ivan Hewett

Yahoo News

Yahoo News