Regina Spektor finds God, and MUNA channel a Year Six disco – the week’s best albums

Regina Spektor: Home, Before and After ★★★★★

Regina Spektor’s eighth album opens with a strong gambit, as the Russian-American singer-songwriter describes an encounter with God on a New York street corner, conjuring this mystical visitation in cheerfully mundane terms: they decide to “grab a beer” and “we didn’t even have to pay / 'Cause God is God, and he’s revered”. Naturally, she has questions: “Why doesn’t it get better with time?” she wants to know, evoking the confusions and challenges of life with a particularly artful verse: “I just want to ride / But this whole world / It makes me car sick / Please stop the meter, sir / You have a heart / Why don’t you use it?”

This audacious flourish of fantasy and philosophy is bundled up in a melody of almost throwaway loveliness, in which Spektor’s delicately flowing piano playing and liltingly conversational singing are supported by a glorious orchestration, the song shifting from ethereal whimsy to lushly vigorous bombast as the narrative itself expands and retracts. It is a hugely impressive start to another quirkily eccentric yet pointed, powerful, sensuous and amusing collection displaying songcraft and performances of the very highest order.

Spektor’s devoted fan base would expect nothing less, but there is still a sense that the mainstream is playing catch up with an exceptional talent. Revered by those in the know (admirers include Peter Gabriel, Lin-Manuel Miranda and the Obamas) and much favoured by TV soundtracks (she has featured in such shows as Grey’s Anatomy, Sex Education, The Good Wife and provided the theme tune for Orange is the New Black), Spektor has the status of one of the defining artists of the millennial generation, yet the 42-year-old has never scored anything as vulgar as a hit single. Maybe she is just too odd for household-name status, but she has the talent to play the long game and sometimes it can take the world a while to catch up. Just ask one of her great musical heroes, Kate Bush.

Home, Before and After is Spektor’s first offering in six years, and its backdrop has been informed both by parenthood (she has two young children) and losing a parent (her hugely supportive father died this year). The cosmic mysteries of time are explored on a wondrous nine-minute centrepiece, Spacetime Fairytale, which unfolds like Stephen Sondheim orchestrating a psychedelic odyssey and includes a flourish of delicious ragtime piano and a tap dance. Such incongruities are key to Spektor’s appeal: these are songs you cannot imagine anyone else composing, and yet (under the sympathetic production of John Congleton) they sound like fully rounded works, not eccentricities bending rules for the sake of it.

Spektor can certainly craft a pop song if she wants to, as she demonstrates with the bass-bubbling Sugarman, a subtle portrait of a kept woman dressed up as ear candy. It finds almost its diametric opposite in One Man’s Prayer, a lovelorn ballad that gradually reveals itself as a dark “incel” anthem, exposing the poisoned logic of misogyny. Opposites abound in Spektor’s world, made manifest in nursery rhyme showtune What Might Have Been, a parade of contrasting pairs that includes “Bombing and shelters go together”.

Born in Russia, raised in America, with grandparents in the Ukraine, Spektor has spoken of her anguish at the current conflict, which began after this album had been recorded. There are no songs of war and peace, yet pulsing throughout is an uplifting love of life and pure joy in the expression of music in the face of adversity. The closing track, Home, offers a reassuring lullaby for troubled times: “By tomorrow may it pass / Like a shadow or a storm / Without darkness there is there light / Without night is there a morning.” With Home, Before and After, Spektor surely proves she is a songwriter for the ages. Neil McCormick

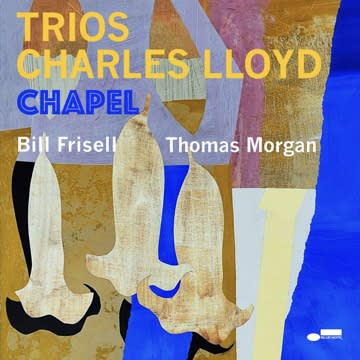

Charles Lloyd, Trio of Trios★★★★☆

Age doesn’t always bring wisdom, but it certainly has in the case of venerable saxophonist, flautist and composer Charles Lloyd. Now aged 84 and laded with every honour the jazz world has to offer he’s embarked on three new recordings, each with a differently constituted trio. The first of them, Chapel, on which he’s joined by guitarist Bill Frisell and bassist Thomas Morgan, has no connection with anything ecclesiastical; the name refers to the chapel in San Antonio where the trio first played together. However the spiritual connotation of the title is exactly right, though it’s not that ecstatic striving for the sublime you find in ‘spiritual’ jazz musicians like Sun Ra. It’s more a meditative ripeness about the playing of all three musicians, and a gentleness in the sound-world.

As for the music, it’s centred on three tenderly lyrical compositions with which Lloyd made his name in the 1960s, when he led a fabulous quartet that included the young Keith Jarrett and drummer Jack DeJohnette. One of them Song My Lady Sings transforms magically at the halfway point from a beautifully entwined duo for Morgan and Frisell to a rich trio texture. Beyond Darkness has a gently Latin flavour, mysteriously tinged with something darkly Spanish, while Dorotea’s Studio is a perfectly turned tribute to Lloyd’s partner Dorothy Darr. Alongside these are seemingly casual versions of two standards, Billy Strayhorn’s Blood Count and Bola de Nieve’s Ay Amor. One of the mysterious charms of the album is the way the players seem to have all the time in the world, and yet overall each number feels very focused. After all Lloyd‘s restless explorations in ‘world music‘, from the Balkans to Africa to Latin America, this album feels like a homecoming enriched with subtle hints of those many musical journeys. Ivan Hewett

Giveon: Give Or Take ★★★☆☆

There’s a characteristic quality, as well as a first-name informality, to 27-year-old Californian singer-songwriter Giveon. Over the past couple of years, his rich baritone vocals and plaintive delivery have proved a stand-out attraction on hit R&B/hip hop/pop collabs such as Chicago Freestyle and In The Bible (with Drake) and Peaches (with Justin Bieber). As a teen, Giveon apparently found his creative voice through listening to classic singers ranging from Frank Sinatra to Barry White; such multi-generational inspirations also extend Giveon’s own appeal, lending an old-school atmosphere to his contemporary slow jams.

Give Or Take is pitched as Giveon’s debut album, although it also follows his substantial EP releases, both released in 2020: Take Time (which, slightly confusingly, was Grammy-nominated in the Best Album Category), and When It’s All Said And Done. He remains in assured, familiar mode here: cast as the bruised romantic on melodies such as the pleasingly dreamy openers Let Me Go and the string-inflected Scarred; navigating fame as a lonesome artist on the road (“Put your number in my phone, but don’t save it,” he sings on Lost Me); and sometimes lamenting the stresses of grown-up life (At Least We Tried; Unholy Matrimony). On the track Dec 11th, Giveon serenades a nameless fan with “pretty brown eyes”, before his dedication is drowned out by crowds chanting his name.

The songs are interspersed with voice notes, including phone call clips from Giveon’s proud mother; it’s not the first time that he’s featured interludes, and such spoken word reflections recall older eras of R&B records as well as more recent big-hitters like Adele. It’s a technique that can sound intimate but also feels slightly affected. Give Or Take presents Giveon as an undeniable talent who isn’t inclined to go deeper than his comfort zone for now; he coasts quite sweetly, between heartache and humblebrag. Arwa Haider

MUNA: MUNA ★★★★☆

Nowadays, much of what is touted as ‘queer music’ seems to be a free-pass at mediocrity. Not to name names, but for some, that ‘queer’ mantel can take on a lot of work – it’s an easy signpost for something radical and progessive and modern and interesting – even when the music is anything but.

I am therefore delighted to report that Muna, the cult-meets-mainstream pop trio – who make music as a love letter to both their younger queer selves and a new generation of fun-loving queers – are far from mediocre.

The self-titled MUNA, their first album since being dropped by RCA and consequently singing to Phoebe Bridgers’ Saddest Factory Records, hits a very sweet spot. It’s full of experimental and intelligent sound design (particularly on Runner’s High, a post-dubstep track with cacophonous synths and start-and-stop drops) so sensuous and slick that it comes across as emotionally urgent rather than cerebral. It’s music so joyous and deceptively left-field that it wouldn’t sound out of place at a year six disco as well as a Rough Trade store. That’s certainly no mean feat.

The album is both consistently breezy and emotionally upfront, going to-and-fro between galvanising dance anthems and gentle, psychedelic country ballads à la Kacey Musgrave’s Golden Hour.

However, where Golden Hour felt like a celebration of loneliness, MUNA instead feels community-facing. There’s introspection, yes (particularly on the lovely cowboy ballad Kind of Girl, sung by the group’s guitarist and backing singer, Katie Gavin) but it feels more like soliloquising in front of a large crowd rather than an internal monologue.

If we have to be alone, let’s be alone together; if we have to go through heartbreak, let’s dance our heartbreak away together – that’s MUNA’s missive. Their music strives to make you feel both vividly alive and a part of something. It’s why, even when the record’s over, it’s hard to tear yourself away from their world. Emma Madden

Soccer Mommy, Sometimes, Forever ★★★★☆

Who runs the world? In indie-rock in 2022, it’s undoubtedly the girls: Mitski, Phoebe Bridgers, Sharon Van Etten and Angel Olsen seem to be on an unstoppable rise to the top as the voices of a generation disillusioned with life and love.

Then there’s Soccer Mommy, another member of that acclaimed gang, whose music always manages to find hope in the darkness. Formed by vocalist and guitarist Sophie Allison in 2015, Soccer Mommy’s third album, Sometimes, Forever, is an endearingly vulnerable insight into the world of Gen-Z. The band got producer Daniel Lopatin (The Weeknd, the Uncut Gems soundtrack) on board to mix up their usual indie-pop sound, and it paid off, delivering a record filled with the influence of pop-punk, shoegaze and soul. With U and Unholy Affliction both feature heavier riffs and cymbals that suit Allison’s brooding vocals – which echo previous female trailblazers like Paramore’s Hayley Williams and Cocteau Twins’ Elizabeth Fraser – perfectly.

Nashville-raised Allison was just 20 years old when the band (also featuring Thomas Borrelli on drums and Kelton Young on lead guitar) released Clean, a debut which became one of the most beloved coming-of-age albums of the 2010s; Color Theory, its 2020 follow-up, centred on Allison’s battle with depression and her mother’s terminal illness – its rawness earned it a Grammy nomination.

Sometimes, Forever, though on the whole a rockier, more grown up record, still has its moments of teenage innocence: Shotgun and Feel It All The Time seem like continuations of the biggest singles from color theory, royal screw up and circle the drain, that became sad anthems for disenchanted youth. Listening to Shotgun, with its gloriously catchy chorus (“So whenever you want me / I’ll be around / I’m a bullet in a shotgun waiting to sound”), it’s easy to imagine thousands of adoring faces in a crowd staring up at Allison, the singer who managed to put a pen to paper – and a voice to mic – to explain feelings they’re familiar with. “I don’t know how to feel things small,” she sings on Still, the album’s closing track. “It’s a tidal wave or nothing at all.” It seems like an apt metaphor for a band who don’t believe in emotional compromise. Poppie Platt

Yahoo News

Yahoo News