Revisiting the Tough, Terse Musical Icon Lee Hazlewood

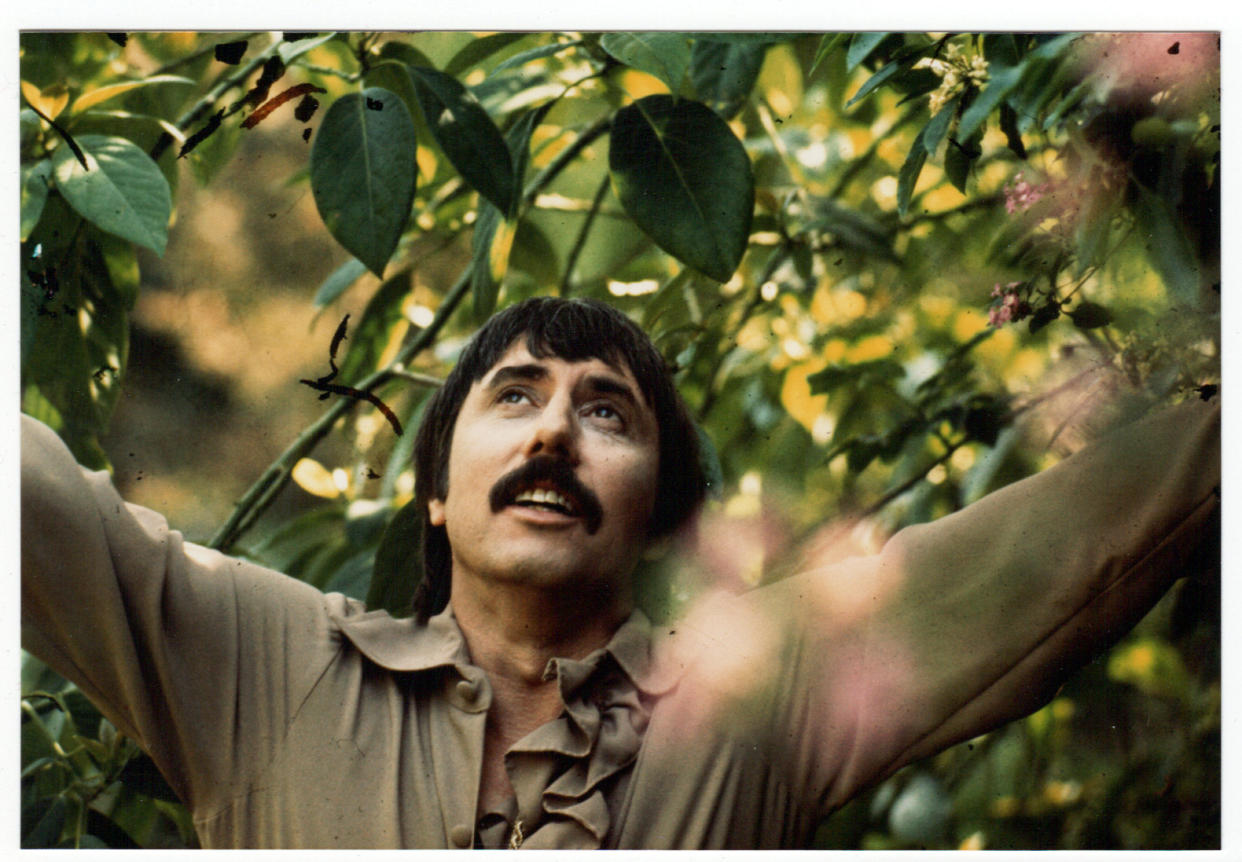

A gruff, lysergic cowboy is the baritone voice behind some of history’s most celebrated pop songs. You just wouldn’t know it. That’s partially because Lee Hazlewood, the producer known for his prolific output and for penning Nancy Sinatra’s smash 1966 hit “These Boots Were Made For Walkin’,” never wanted to be a vocalist. But when he did sing in his bombastic low register, hearts shuddered and the wind blew in a different direction.

Born in Oklahoma, the rough-and-tumble Hazlewood held dozens of odd jobs until, as he once told ’s Dorian Lynskey, “poverty” led him to enter the music business in the 1950s. He produced and wrote songs for the twangy guitarist Duane Eddy, among others, and following his mega-hit with Nancy Sinatra he formed his own label, Lee Hazlewood Industries, under which he recorded with luminaries familiar and forgotten, including Lynn Castle and the girl group Honey Ltd.

But Hazlewood’s life was more akin to a kind of Greek tragedy than to a fairy tale. Shortly after he met his creative partner and romantic partner, Suzi Jane Hokom, he saw the rise and fall of his record label in the early 1970s. He pissed off record companies and musicians alike, and then disappeared to Sweden. Years later, Hazlewood’s legacy and contradictory personality is still being reckoned with. He was at once a self-deprecating and savvy businessman, a creative force with no self-confidence and at the same time an ego so immense that he once forbade Hokom from recording with The Beatles as they were forging Apple Records.

“Who is Lee Hazlewood? Some people say 'a hell of a good old voice,’ some people say ‘a son of a bitch,’ some people say both in the same sentence,” says Hunter Lea, a musician and Hazlewood historian. “I guess that’s the best way that I can describe the experiences I've heard of people who knew him, worked with him and collaborated with him.” While Hazlewood is perhaps now out of cultural context, Lea offers that “time has equalized” his contributions to art, which is why he’s experiencing a contemporary revival.

Post-punk renegades like Beck, Jarvis Cocker, Nick Cave and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth have been quick to sing Hazlewood’s praises wherever they can, both in cover songs and while giving magazine interviews. In any case, that’s what originally drew a young Lea to delve into all of Hazlewood’s works. Via Smells Like Records, the imprint of former Sonic Youth drummer Steve Shelley, Lea bought his first Hazlewood record, the lucky find 13, which he describes as “weird, drugged-out Johnny Cash and Elvis in a lounge from hell.” He was a man possessed.

By the early 2000s, Lea had amassed a formidable collection of Hazlewood records. In that period, Lea contracted testicular cancer (oddly, at around the same time Hazlewood himself had the cancer that would take his life in 2007). But the illness merely increased his impulse to discover as much as he could of Hazlewood’s immense output. “I had to go through chemo and was out of commission for a while,” he says. “Something that was fun for me to do was discovering LHI Records.” He used a now-defunct Hazlewood superfan’s website as a sort of checklist, and set out on the challenge of collecting every record within Lee Hazlewood Industries’ catalogue, which spanned from 1966 to 1971.

Lea then proceeded to make music of his own, too. “I went to a recording studio and said, ‘I want to book some sessions and make a record before I die.’ And so I booked time, we made a record,” he says. “It was pretty scary but it also...took nearly dying to put out a record.” The experience would prove to be life-altering: Soon afterward, Lea and his band opened for Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker during a Seattle show, and following the record’s release, they performed at the Bumbershoot Festival. There, Lea met Matt Sullivan, of the label Light in the Attic Records, which was making the transition from a new-release label into the archival, reissue outpost it is today.

He mustered the courage to approach Sullivan, and proposed a Lee Hazlewood box set and reissue series based on the collection of Lee Hazlewood Industries Records he’d amassed. “He said, ‘Think they’ll sell?’ And I said, ‘Well...maybe not. But I think it’d be really good.’” This isn’t the first attempt at making an extensive Lee Hazlewood reissue series, though. Lea says that back in the ’90s, Mark Pickerel, the former drummer of the grunge mainstay Screaming Trees, was trying to put together a Hazlewood series for Sub Pop. “Nirvana and all these bands had agreed to do a Lee Hazlewood tribute album," Lea says, "But in the end Lee wanted too much money [and] it failed."

So Sullivan and Lea pulled together their resources and recruited Suzi Jane Hokom, the seasoned vocalist (and Hazlewood’s longtime girlfriend and collaborator), for her perspective. “At that point, people weren’t even really sure if she existed. There were things on the Internet saying, ‘Oh Suzi was just a pseudonym for Nancy Sinatra,’” Lea says. The series began as an overview, but eventually morphed into what he calls “a time capsule of every Lee Hazlewood record.”

In late January, Light In the Attic reissued three of Hazlewood’s rare solo albums: The Very Special World of Lee Hazlewood, Something Special and Lee Hazlewoodism: It's Cause and Its Cure, which shows his talents in French ye-ye, country-inspired licks and standout pop alike that he produced for MGM between 1966-1968. Listening to them, it’s almost impossible to believe that Hazlewood derided his own vocal talents. “That’s the great irony of Lee Hazlewood: He didn’t think he was a singer at all,” Lea says, mentioning that it was more about the money for the shrewd Hazlewood. “He made a body of work that in the end, almost in an exploitative way, was really good. Every person I talk to says that the greatest part of Hazlewood. was him as a writer, and that’s really where his soul is.”

There are more Hazlewood records on the way, Lea says, both his own and others he produced. Say what you will about the current musical landscape, but the move toward archiving and toward digitizing records is making such things all the more accessible. And it’s possibly mobilizing a new legion of Hazlewood fanatics. “We live in an amazing era to be music lovers,” Lea says. “It’s all being unearthed, and maybe there’s not enough time in the day in the ’60s to play all the great songs that were being recorded.” We’d say that’s a great problem to have.

Related Articles

Yahoo News

Yahoo News