Sidney Poitier, actor and director who starred in To Sir, With Love and In the Heat of the Night – obituary

Sidney Poitier, who has died aged 94, was the first black film actor to become a big box-office star and was admired by white and black cinema audiences alike for the subtle integrity of his acting and for his striking good looks.

Until Poitier emerged on the scene in the 1950s, black actors were mainly typecast as entertainers, servants or clowns. Poitier broke the mould when he appeared on screen as a doctor confronted by the racist hoodlum played by Richard Widmark in Joseph L Mankiewicz’s No Way Out (1950), a film so outspoken for its time that it was banned in the South and even censored in some northern states.

His character was the first of a succession of quietly spoken doctors, lawyers, social workers, teachers and cops who Poitier was to portray over the next 20 years. They were roles in which Poitier combated prejudice and injustice with the moral weapons of fortitude, stoicism and dignity, his anger expressed only through the hypnotic eyes that interrogated antagonists and audience.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Poitier broke down racial stereotyping in a string of hit films including Cry, the Beloved Country, Blackboard Jungle and The Defiant Ones, as well as Ralph Nelson’s Lilies of the Field (1963), in which his portrayal of a kindly itinerant labourer helping a party of East German nuns in Arizona brought him an Oscar for Best Actor. He was the first black actor to win the award.

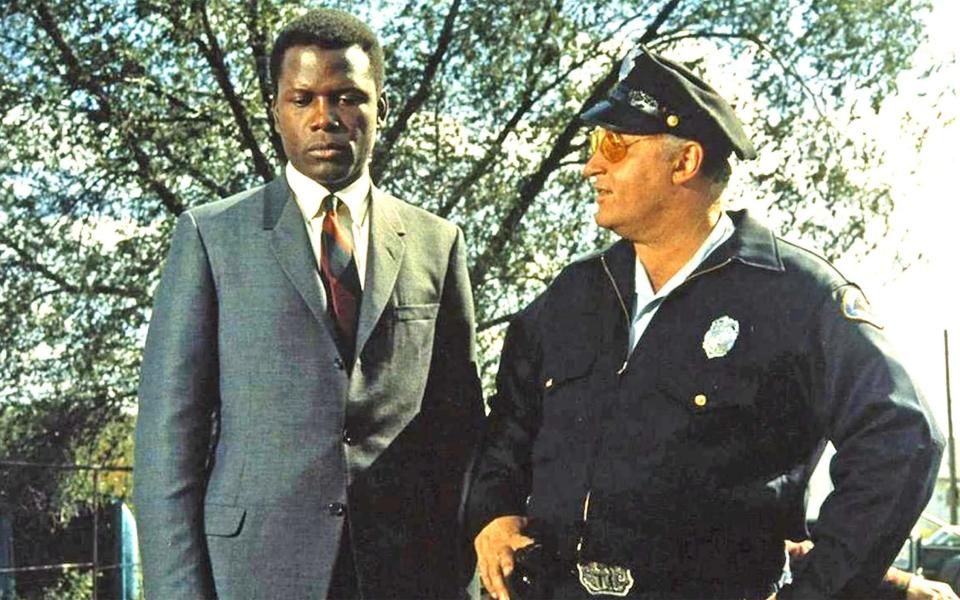

In the summer of 1967 Poitier held the three top spots on the box-office takings list with Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night, To Sir, With Love, co-starring Lulu and Judy Geeson, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, with Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn.

Undoubtedly Poitier’s most enduring role was as Virgil Tibbs, the Philadelphian detective pulled into a murder investigation run by Chief Gillespie (Rod Steiger) in a small town in the Deep South in In the Heat of the Night. The film won five Academy awards, including Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and one for Rod Steiger, and is now recognised as a classic study of racial inequality in America. Poitier gave one of his most intelligent and understated screen performances, his restraint in the face of Steiger’s careless prejudices pointing up a deep sense of injustice and rage lurking beneath the surface.

Poitier was not surprised when the film was banned in many southern states. But the film came out just at the point when more aggressive black voices preaching separation were seizing the initiative from the old-style civil rights campaigners, and he was shocked to find himself under attack from black activists, too.

In his memoir, The Measure of a Man, Poitier recalled that “There was more than a little dissatisfaction rising up against me in certain corners of the black community. The issue boiled down to why I wasn’t more angry and confrontational. According to a certain taste that was coming into ascendancy at the time, I was an ‘Uncle Tom’ for playing the ‘noble Negro’ who fulfils white liberal fantasies.”

The charge had some validity in the case of Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, in which Spencer Tracy has trouble deciding whether he will allow his daughter to marry Poitier, a doctor of international renown who is on the point of winning a Nobel Prize, but none at all in the case of In the Heat of the Night.

Nonetheless, the popular denunciation of Poitier throughout the late 1960s and 1970s knew no bounds. In 1978 he was cruelly satirised in Amiri Baraka’s play, Sidney Poetical Heroical, as a front man for white liberal fantasies of racial harmony. In 1981, The New York Times published an article entitled “Why do white folks love Sidney Poitier so?”

Rejecting the idea of cultivating a more confrontational screen persona, Poitier turned to directing, with some success, but he became increasingly depressed with the film industry and with the entrenched attitudes of the various sides in the race debate. It was only towards the end of his career that Poitier was recognised for his huge contribution to changing the way in which American society regards black people.

Sidney Poitier was born on February 20 1927 during a visit by his Bahamian parents to Miami. He weighed only 3lb and was not expected to survive. He grew up on Cat Island in the Bahamas, where his father, Reginald, grew tomatoes.

In 1936 the state of Florida imposed an embargo on Bahamian tomatoes to protect its own growers, forcing Bahamian farmers into destitution. The following year, Poitier’s mother, Evelyn (née Outten), took her children to Nassau, a magnet for cheap labour at the time.

The young Poitier first learned the meaning of racial prejudice aged 13 when, walking up a street, he noticed a white teenager cycling towards him on the opposite pavement. “He rode up, and as he got abreast of me he took his right hand off the handlebar and punched me in the face.” Poitier gave chase but the boy rode off.

The family moved to Miami and Poitier, still in his teens, ran off to New York, where he took a succession of odd jobs – dishwasher, cleaner, construction worker – and spent a year in the US Army. With no home to go to he slept in bus stations and on pavements.

In 1945 he wandered into the American Negro Theatre on 127th Street and asked for an audition. The director advised him to go back to washing dishes but Poitier refused to be deterred, and was eventually rewarded with regular stage work. He made his public debut in Days of Our Youth, standing in for Harry Belafonte. This led to a small role in Lysistrata, when he stole the show. He continued to perform in plays until 1950, when he made his film debut in No Way Out.

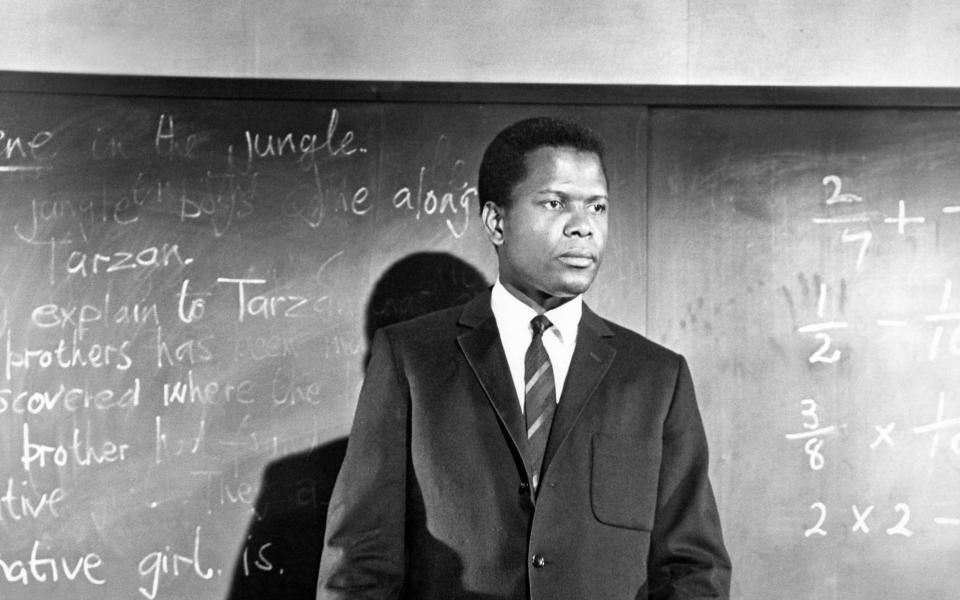

It was Poitier’s first mainstream picture, Blackboard Jungle, released in 1955 and based on Evan Hunter’s ferocious attack on inner-city schooling, that established Poitier in the popular consciousness. As Gregory W Miller, an angry but likeable pupil at a New York trade school, he produced a performance which challenged the segregated education system. The film – banned in the southern states – was released in the same year as the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favour of desegregation.

Following this success, Poitier moved to Hollywood, where he consolidated his reputation in Martin Ritt’s Edge of the City (1957) and Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958), for which he won an Oscar nomination for Best Actor for his performance as a convict on the run manacled to a racist redneck (Tony Curtis). The film ended with both men learning to ignore the fact that their skins are different colours. Black separatists never forgave Poitier for the closing scene in which he holds his dying buddy in his arms.

In 1959 Poitier returned to the stage as Walter Lee in Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun, the first play by a black female playwright to show on Broadway. He would reprise the role for the Hollywood adaptation in 1961.

One of his best roles in the 1960s was as the sardonic journalist sussing out cold warrior Richard Widmark aboard a US warship in The Bedford Incident (1965).

After Poitier found himself the target of criticism from sections of the black community, he retreated to the Bahamas for a few years. When he re-emerged in the early 1970s, it was as a director. Beginning with the Western, Buck and the Preacher (1972), he made a series of highly entertaining films, including the romantic drama A Warm December (1973), the crime capers Uptown Saturday Night (1974, starring Bill Cosby and Harry Belafonte) and Let’s Do It Again (1975, also staring Cosby), and the prison comedy Stir Crazy (1980, starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor).

The popularity of these films in the black community paved the way for succeeding generations of black television sitcoms and opened up a new sector for black artists.

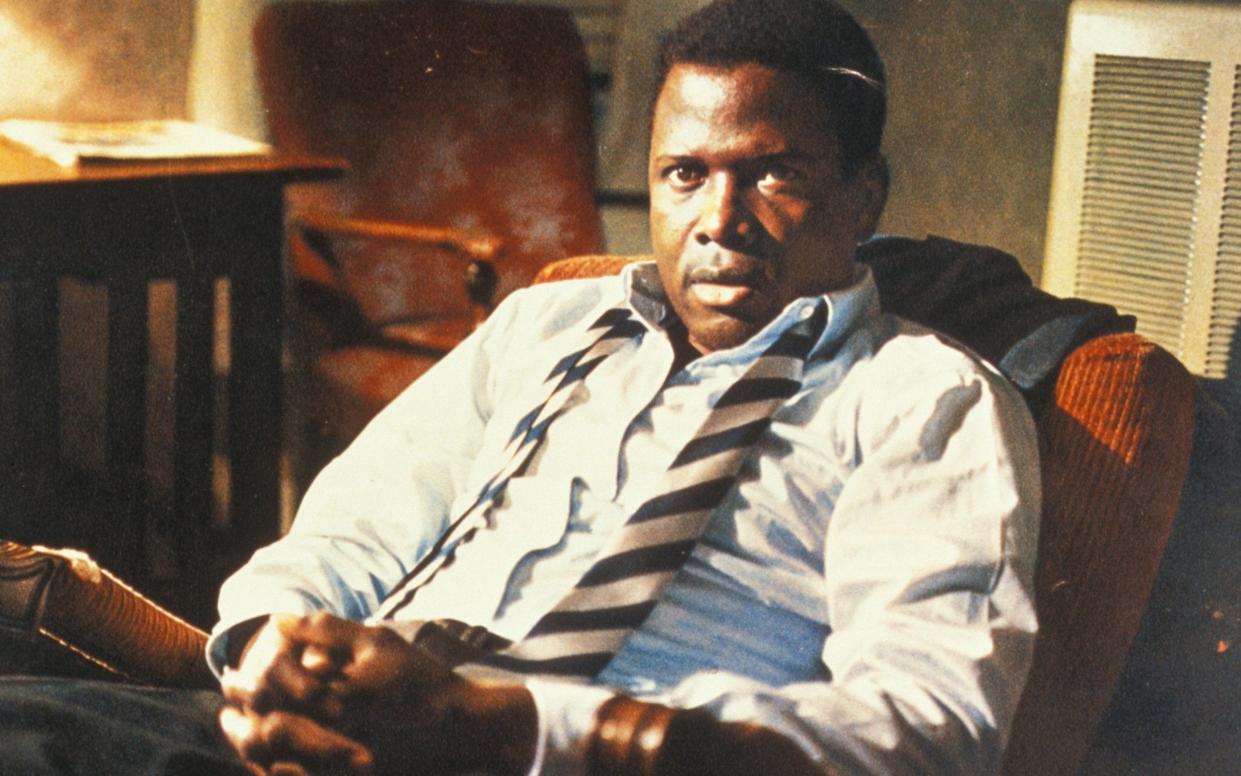

In 1988 Poitier returned to the screen giving weight to Roger Spottiswoode’s Deadly Pursuit as an FBI chief, and he followed this up with Sneakers (1992), in which he played a former senior CIA man, and The Jackal (1997) – a loose remake of The Day of the Jackal – in which he was the deputy director of the FBI.

The same year, he played Nelson Mandela in a television docudrama, Mandela and de Klerk. He also figured strikingly in a film in which he did not actually appear – the screen version of John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation, a dramatisation of the true story of a trickster who entered Manhattan society by posing as Poitier’s son.

By now Poitier’s achievements had begun to receive their due recognition. In 1974 he had been appointed an honorary KBE. In 1994 he was appointed company president of Walt Disney and in 1997 was named the Bahamas’ non-resident ambassador to Japan. He was given an Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 2002, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009, and was made a Fellow of Bafta in 2016.

He wrote three volumes of memoirs: This Life (1980), The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2000) and Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My Great-Granddaughter (2008).

Sidney Poitier married first, in 1950, Juanita Hardy. The marriage was dissolved in 1965, and in 1976 he married Joanne Shimkus. She survives him with their two daughters, and four daughters from his first marriage.

Sidney Poitier, born February 20 1927, died January 6 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News