Simon Napier-Bell: ‘I arranged for Wham! to play Communist China’

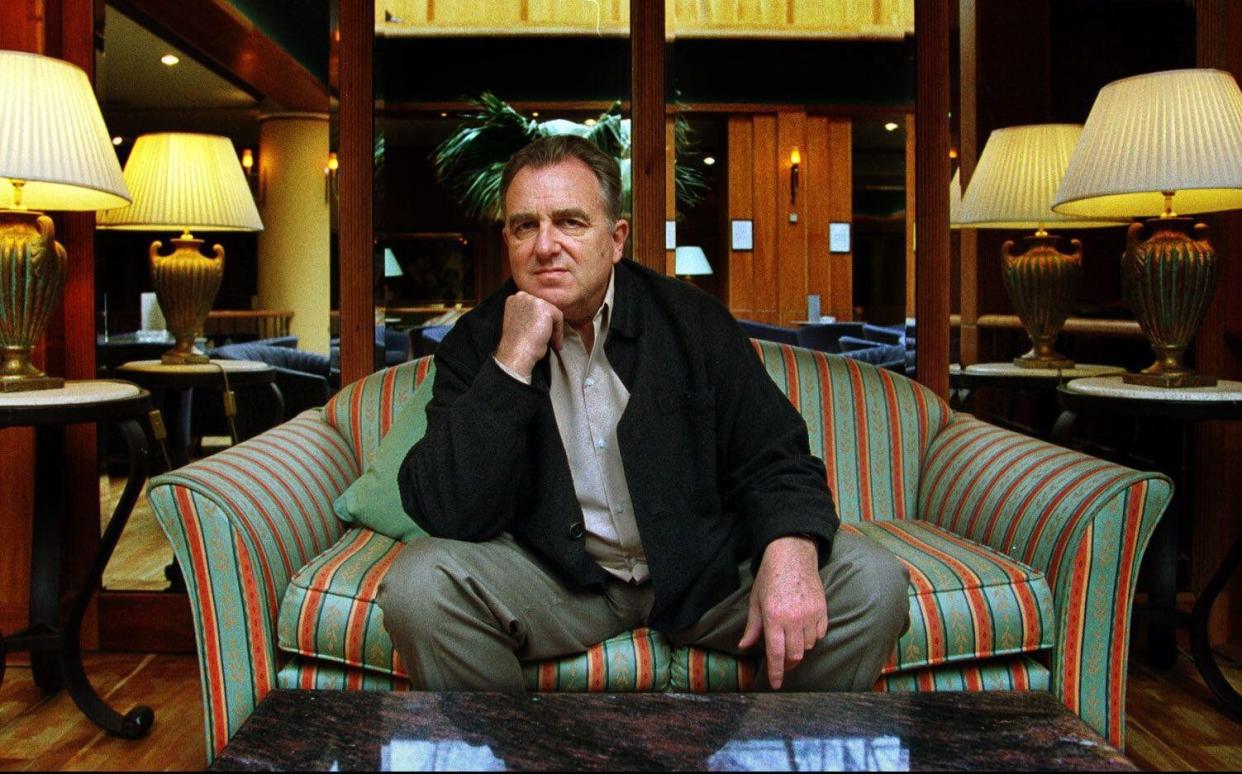

Simon Napier-Bell, 83, is best known for managing the Yardbirds, Jimmy Page, Ultravox, Marc Bolan, Japan, Asia, Candi Staton, Boney M, Sinéad O’Connor and Wham!

In the 1960s he co-wrote You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me, a hit for many artists including Dusty Springfield and Elvis Presley.

He has also been a record producer and is now a writer, filmmaker, public speaker and consultant. He lives in Thailand with his husband.

Did you have a comfortable start in life?

My father was a documentary filmmaker and always short of money. I switched from private to state schools, depending on our fluctuating fortunes.

He had a posh accent but was fervently Left wing.

On Sunday mornings he’d cycle from our nice middle-class home in the best part of Ealing, west London, to the worst working-class areas of Acton to collect donations for The Daily Worker. We used to return with a meagre five shillings, but he obviously liked the duty of doing it.

What was your first job?

When I left school at 17 I answered an ad in Melody Maker appealing for a band boy for Johnny Dankworth’s Orchestra. I was paid £3 15s a week. I had to pack and unpack the drums when they toured each week and set them up at the venue.

A year later I decided to move to America to soak up jazz but couldn’t get a visa, so I went to Canada. I played trumpet in a pub but I was a very average musician so I returned to London.

Why did you switch to film editing?

During my school holidays I’d worked with my father’s film company, where I picked up the basics of editing.

One of my best-paid jobs was working on the score for What’s New Pussycat? with Burt Bacharach. We were amazed we’d got him, but he didn’t know about writing film music. Instead of writing a score, he wrote 47 different tunes for the 47 music sections, recorded them and flew home.

The next day the producers said: “It’s a disaster. Our contract says we have to use his music. Can you turn this into a score?”

Being a precocious little 25-year-old, I said: “Of course.” I took the two main songs, threw everything else away and worked on them for four weeks without stopping. I ended up being paid double-double-double time. It’s the most I’ve made in my life.

What was the most successful band you managed?

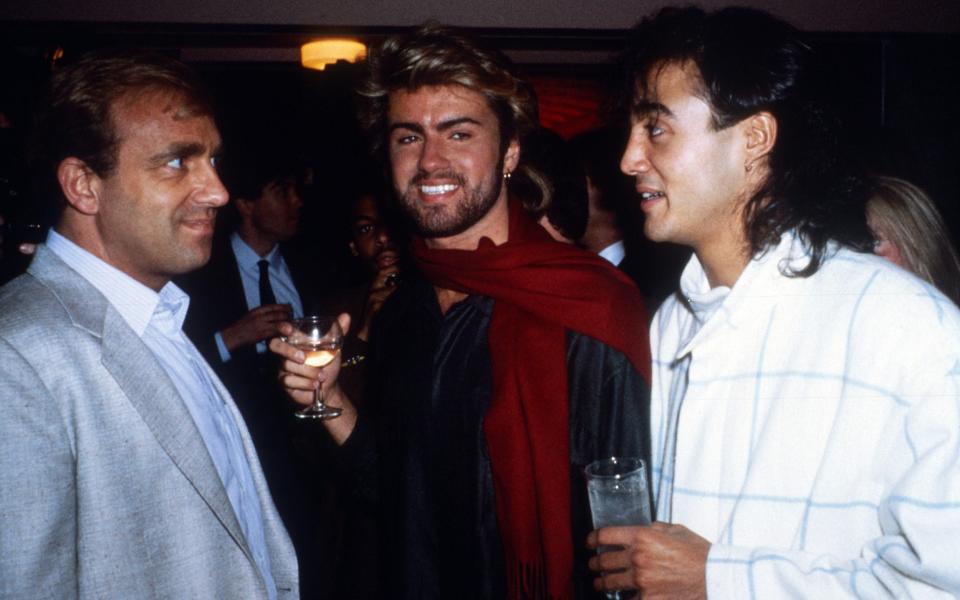

By the time they were 19 George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley of Wham! had their first millions in the bank. I co-managed them with Jazz Summers and we took 12.5pc of their net earnings.

It took us 18 months to make them big in America and we did that by making them the first Western pop artists to play in Communist China. The group didn’t have any money when I started the negotiations, so for the first year I funded all the costs myself.

This became quite expensive because I’m not inclined to travel economically. As I got higher up the ranks, the lunches I was expected to pay for grew more and more extravagant.

There was also the cost of staging Wham’s first concert in Beijing, not to mention the accompanying documentary film. It cost £1m in total. The gamble paid off, of course.

Was George Michael a shrewd businessman?

He was the most financially correct person you could hope to work with, but he gave away a lot of the money he made and didn’t always think through the implications.

When, for example, he donated all the royalties from Wham’s 1984 hit single Last Christmas to Ethiopian famine relief, he’d overlooked the fact that he was supposed to split the royalties with Andrew and had to pay a management fee percentage. That took a lot of sorting out.

Later on, he also failed to budget for lean times when he wasn’t producing hit songs.

Have you ever struggled to pay the bills?

In 1987 I was astonished to receive a £4.8m tax demand when my total gross income had been about £280,000. This figure was more than Wham! had earned gross the entire year.

My accountant said the tax people did these things to bring you to the negotiating table because I’d been a foreign resident for 20 years and had just returned to live in the UK.

When I met the tax inspectors they said: “Foreign residence is not a status we grant officially, we allow it ex gratia. This means you have to prove it if we ask you to. And I’m sure you know the rules – you can’t be in the country for more than 90 days in any one year.

“Now let’s suppose in one of those years since you pronounced yourself a foreign resident you happened to be here for more than 90 days. We could then withdraw our tacit agreement that you were not resident here and look back at all the years since you started to be, with no six-year limitation on claiming from you.”

“If in 1970 you earned £10,000, for instance, under the tax regime of the time you would have been required to pay tax at the then current rate of 84pc and, on top of that, compound interest until today. And that is just one of 17 years. Moreover, we would be prosecuting during each of those years for tax avoidance.

“With court costs and your time involved, and the possibility of a penalty that could include imprisonment, wouldn’t it be easier to pay the few million pounds we’re asking?”

I said yes, but I hadn’t got it. And then, as my accountant pointed out, to pay the £4.8m I’d have to earn it, and if I earned it I’d have to pay 50pc in tax, so I’d have to earn £9m to pay £4.8m.

What did you do?

The only way out was to go bankrupt. We first put the company into liquidation, but because I’d guaranteed most of the company’s debts I had to go personally bankrupt too.

When I made the trip to the official receiver’s office they asked me to fill in a form and pay a £15 fee. I said: “I don’t have £15. All I have is five quid and I’ll need that for my Tube fare home.” They said: “If you don’t have the £15 you can’t go bankrupt.”

The next Monday I paid the fee and went through a demeaning meeting with the official receiver. Afterwards he smiled and said: “Congratulations. You are now officially bankrupt.”

Then he handed me a cassette. “It’s my nephew,” he said. “Everyone in the family thinks he’s awfully good. Maybe you could make him a star.” Outside, I dropped it down a drain.

‘Sour Mouth, Sweet Bottom: Lessons From A Dissolute Life’ by Simon Napier‑Bell is out now (Unbound, £20)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News