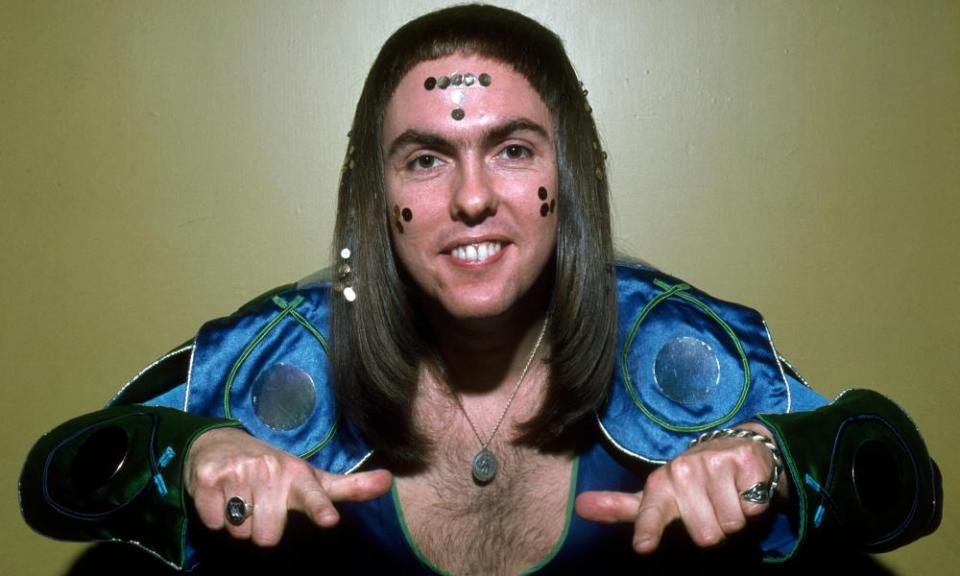

Slade guitarist Dave Hill: ‘I’d come out of work, put on my costume and suddenly I’d be Superman!’

It’s half a century since glam rock first dazzled Britain, and Slade had their first hit, Get Down and Get With It. All four members of the original lineup are alive and kicking, but Dave Hill is now the only one who trades under the name Slade. As is the way of rock bands, there have been sulks, tiffs and the odd tempestuous row. But today Hill is the very picture of Zen calm.

While singer Noddy Holder is remembered as the one with the rasping voice, bassist Jimmy Lee as the creative one (he was classically trained and wrote the songs with Holder), drummer Don Powell as the one who had the terrible car crash that killed his girlfriend and left him in a coma, lead guitarist Hill was always the crazy one. He was famous for his pudding-basin fringe, glittering face, gold capes, mighty stacks (disguising his diddy, 5ft 4in stature) and ray-gun-shaped guitar called Super Yob. In his heyday, he drove a silver Jensen Interceptor and a gold Rolls-Royce with the number plate Yob 1. Hill was marketed as the yob’s yob.

He may not have sung the songs, but Hill was very much front of house as Slade became huge in the 1970s – six No 1s, most of the titles deliberately misspelt; the first band to have three singles enter the charts at the top spot (Skweeze Me, Pleeze Me, Cum on Feel the Noize and Merry Xmas Everybody); more than 20 Top 30 hits. They were as famous for their inane feelgood lyrics as their raucous pop-rock. Later on, they wrote a number of poignant ballads (Everyday, How Does It Feel, In for a Penny) that weren’t quite as successful, but may well be their finest songs.

When I had short hair, my ears used to stick out like Spock. I had a complex about the size of them

Hill, 75 next month, is still as Dave Hillish as you could hope for: thick Black Country twang, buck-toothed, grinning, garrulous, long hair covering his ears, though the fringe has receded into yesteryear. He Zooms from the studio at his Wolverhampton home. I can see eight guitars on the wall and a keyboard to his side. This is where he has been creating throughout the pandemic. He is working on a solo album, writing a book on glam fashion to mark the genre’s 50th anniversary, and waiting for the relaxation of lockdown rules so that he can get Slade back on the road – even if it will be without Powell, with whom he acrimoniously parted company last year.

I show him an old, faded photo: me at the age of nine, with two framed pictures of Slade behind me. “Do I take it you’re a fan?” he asks, delightedly. For many people in their 50s, Slade were the band. Noel Gallagher is a huge fan. In the afterword for Hill’s anecdote-packed memoir So Here It Is, Gallagher wrote: “No Slade = No Oasis. It’s as devastating and simple as that. The Beatles? Well they were undeniably great … but Slade? I felt their songs could’ve been written at the end of our street … in a house just like mine.”

The Slade boys were quite different from their uncouth image. Holder and Lee were upwardly mobile working-class boys, while Hill had a fascinating background. “I was certainly not a yob,” he says. “We all came from very good families. Each one of us had mums and dads who stayed together.”

Hill’s mother, Dorothy, came from a refined middle-class family (her father was a doctor of music and classical pianist), was supremely bright and had a very successful secretarial career. At the age of 17, Dorothy became pregnant, and had a girl called Jean. The father was never named, and Jean was brought up by the family’s housekeeper. Dorothy ended up living on a Wolverhampton estate with Hill’s father, Jack, a mechanic, and it was here that the young Dave grew up. He says that his mother never overcame the shame of having Jean out of wedlock, had severe depression, spent time in psychiatric hospitals and died in her 60s. After her death, Hill discovered she had kept another secret. “We didn’t know she was a war-cabinet minister’s secretary.” Your story is made for the TV show Who Do You Think You Are?, I say. He grins. “Jean’s father was a married man, we believe – it could be a politician for all I know.” The cabinet minister? “It could be.”

Hill learned to play guitar at 13, dossed at school, and at 15 got an office job at Tarmac that he hated. A couple of years later, he left to become a professional musician, and played with Powell in a band called the Vendors. Hill and Powell met Holder and Lee, invited them to join the band (by then known as the ’N Betweens), which was renamed Ambrose Slade in 1969, and then simply Slade.

It was when they discovered glam that things really took off. But this was glam with a difference – working-class, cloth-capped glam. Why does Hill think they became so big? He says they were the perfect contrast to what had just gone before – the introspective, dark end to the 60s. Slade were loud, extroverted and happy. “When you think of the essence of Slade, it’s more about a smile than looking at the floor and being super-serious about politics. Our songs reflect the audience – Cum on Feel the Noize, Mama Weer All Crazee Now.” They peaked in 1973 when three of their four singles entered the charts at No 1. “I remember being driven through London in 1973 and thinking: life cannot get much better than this,” he says.

Was this his happiest time in Slade? No, he says. Success is wonderful, but it brings problems – you’re too busy in TV studios and jet-setting to actually live your life, and there is the pressure of expectation. “Success is not natural to any human being. It is a learning curve of coping. A songwriter can be miserable when he can’t write a song or can’t come up with the one that sounded like the one that worked.”

His best memories go back to the beginning: his last days at Tarmac and first as a professional musician. “I used to come out of Tarmac dressed in a suit then this J2 van comes round to pick me up to take me to a show, and I’ve got my change of costume in there. So I’ve suddenly become Superman. I’ve suddenly become an extrovert.” Growing his hair was a life-changer, he says. “When I had short hair, my ears used to stick out like Spock. I had a complex about the size of my ears. So when the Beatles made it, I felt confident that I could grow my hair, and suddenly you felt more attractive. Girls noticed you. I didn’t get girlfriends before that. I was a little bit odd at school. I was shy, believe it or not. My sister said I was a loner.”

What does he think was his main contribution to Slade’s success? Well, he says, he was a decent guitarist, but the unique thing was his personality. “I let Nod and Jim get on with the writing and concentrated on my playing and my appearances. We used to have a saying in the group: you write them, and I’ll sell them.”

In 1974, they tried to break the US. Their record label, Polydor, thought it was inevitable – after all, they were the biggest band in the UK. They were presented as the new Beatles, which was overegging it somewhat, and the US didn’t buy it. “America was getting over Vietnam, and a lot of the hit songs were post-Woodstock.” The Americans were mid-existential crisis, and weren’t ready for good-time glam rockers singing badly spelled songs about noise, squeezing and craziness. They did have their fans, though. Bruce Springsteen turned up at one of their shows and tried to meet them backstage, Hill says. “One of our roadies didn’t have a clue who he was, and escorted him out. He wasn’t that well known at the time in England.”

When they returned in 1975, Britain had moved on. Their tunes were more melodic, the lyrics more mature, but only one of their four singles reached the Top 10 that year. In 1976 only one song reached the Top 30, then none in 1977. And that was the end of Slade. Or so it seemed.

Was it a shock when they fell out of fashion? “No, it was inevitable. Towards the end of the 70s, punk came along.” Actually, Hill says, he was perfectly content when they stopped making the charts. It just presented a new challenge. “We played the difficult gigs, the gigs where people have chicken in a basket and then go on the dancefloor. People might say: ‘Oh dear, that’s a big decline,’ but we had an armour of fantastic songs so nobody was going to argue with us. We managed to survive that.”

Then, in 1980, they were invited to play the Reading festival as a last-minute replacement for Ozzy Osbourne. While the headliners turned up in their Rollers, Hill says, they turned up in a Ford. Had he lost his money by then? Well, he says, he was never super-rich because he didn’t write the songs (Holder and Lee are said to earn £250,000 a year for Merry Xmas Everybody; in 2009 it was estimated that 42% of the world’s population had heard the song.) Did it bother him that he and Powell earned so much less than Holder and Lee? “It didn’t bother me in the slightest. We were a team, and Nod and Jim were doing the work on the songs, we were getting on great together. There was no issue.”

Nobody thought they stood a chance in front of the heavy-metal audience at Reading. But they were received rapturously, the crowd demanding Merry Xmas Everybody and singing along in the middle of summer. It heralded a mini Slade renaissance, with new hits, such as My Oh My and Run Runaway.

By the end of the 80s, they were old hat again. In 1992, Holder left to pursue a career in acting and TV presenting, and Lee to study psychotherapy. But Hill and Powell added new members to the band and continued for another 28 years. Hill says that by and large he has had a ball. “I may be with a different set of blokes, but the actual experience is the same. It’s the moment of the connection with an audience. What better way could I feel?” He talks about the last gig Slade played before lockdown, at Butlin’s in Skegness. “There were 2,000 people, and everybody was dressed up. They’ve got top hats on, they’ve got funny hairstyles – some look like me, some like Bowie, some like Alice Cooper, and all they want you to do is walk on stage and hit them with the big ones.”

He’s been lucky in so many ways, he says. He and his wife, Jan, got hitched in the 1970s, and they are still happily married with three adult children. And there’s not been a day since he left Tarmac that he’s had to do non-Slade work. Of course, he’s been through bad times. There have been sustained periods of depression, but he has always managed to climb his way out of the pit. He talks about one of his worst episodes, when he even lost his love for music, until the soundtrack of a rock’n’roll jukebox musical intervened. “I’ll tell you when the light came. One day, I put on The Best of Dreamboats and Petticoats, and it sounded great. And I went: something’s happening here. And I rang up my psychiatrist, and she punched the air and said: ‘YES!’”

In 2010, during a concert in Nuremberg, he had a stroke while on stage. “I woke up in hospital all wired up. I was tearful because I felt I’d let the band down. I thought, is this it after all these years?” He feared he would never play guitar again. “The surgeon said it would take time, but it would come back. He said: ‘Drinking coffee is really good for you; I recommend 10 cups a day.’” Sure enough Hill drank his coffee and taught himself to play the guitar again.

Last year, there was another crisis when Powell, who had leg injuries that prevented him performing at Slade’s most recent concerts, released a statement saying Hill had sacked him by email after 57 years together. Hill disputed Powell’s version. “Our parting of the ways has not come out of the blue, and his announcement is not accurate,” he said.

Today, I ask Hill whether he really did sack Powell by email, and, if not, what did happen? For the first time, he clams up. “That was untrue – that’s all I’ve got to say on it. My lawyer said: ‘Do not get involved.’ I know the reasons, and it was painful. And I still have a love for Don, I really do. I don’t really want to get into any discussions about it because it’s personal.”

Do they still talk to each other? “No.” Is there any chance of them getting back together? “No. No. No. I’d rather say to you that I’ve moved on from that. I feel happy at the moment, and I’m looking forward to getting back with the band as it is now.” Powell has since set up his own band.

Hill is keen to change the subject. He reminds me he doesn’t like negativity. One of the things that has kept him positive, he says, is discovering the Romantic poets at the age of 40, and reading Wordsworth for the first time. Ever since, he has been obsessed with him. He closes his eyes and starts talking, rather beautifully, about a poem he can’t remember the title of. “Wordsworth talks about a star that travels with you and refers to it as your soul. ‘Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The soul that rises with us, our life’s Star.’ And the poem talks about how ‘Shades of the prison-house begin to close / Upon the growing boy’, but the growing boy still perceives ‘the light, and whence it flows’.”

The point is, he says, that however far the light moves, you can still see it. He pauses, and opens his eyes, smiling. “Ah yes, it’s called Ode: Intimations of Immortality.” Music, he says, is his light; his life’s star. He talks about how it helped him with his depression and then with his stroke. “I realised then that music is a healer. It’s so much a part of me. And maybe that’s my life purpose until I depart from this place.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News