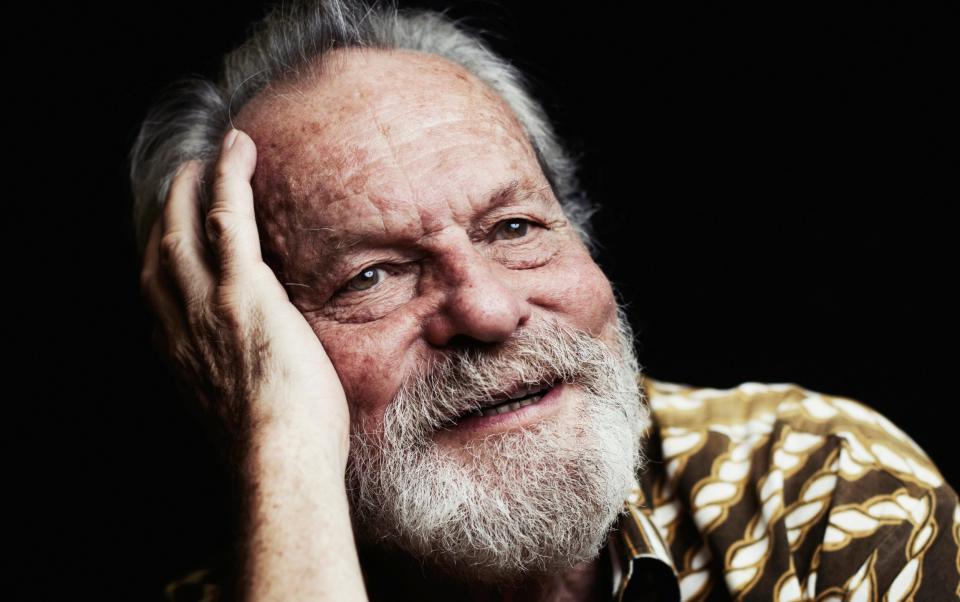

Terry Gilliam on cancel culture: ‘Britain was nirvana for me. But now...’

In a rehearsal room in south London, Terry Gilliam is trying not to tell me the story of how, last autumn, he got into hot water – and ended up in Bath.

“I’m not supposed to say anything!” he whispers, with a mischievous giggle. “There are lots of stories, but we’re not talking about it.”

That “it” is the reason Gilliam, 81-year-old filmmaker and former Python, is unveiling his new revival of Into the Woods – the 1987 musical by Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine that reimagines fairy tales such as Cinderella, Rapunzel and Jack and the Beanstalk – at Theatre Royal Bath this month, rather than at the Old Vic as originally planned.

Last November, it was announced that the London theatre had parted company with Gilliam’s production, despite healthy advance ticket sales; subsequent reports suggested that members of the Old Vic 12 – the theatre’s development group for emerging artists – had voiced concerns over the director’s “previous comments… relating to trans rights, race and the #MeToo movement”.

For example, in 2018, when Shane Allen, the BBC’s controller of comedy commissioning, had a dig at Monty Python (“If you’re going to assemble a team now, it’s not going to be six Oxbridge white blokes”), Gilliam, who was born in Minnesota and went to college in Los Angeles, responded: “I tell the world now I’m a black lesbian.” Then, in 2020, at the height of the #MeToo movement, he suggested he was “tired of white men being blamed for everything wrong with the world”.

Finally, days before the Old Vic’s announcement, Gilliam urged his Facebook followers to watch a new show by American comic Dave Chappelle – “To me he’s the greatest stand-up comedian alive” – which, with its jibes at #MeToo hypocrisy and explicit support for “Team Terf” (so-called “trans-exclusionary radical feminists”), had caused a furore.

“That was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” says Gilliam, who is attempting to combat the room’s sticky summer heat with loose-fitting shirt and sandals. “All I did was say: ‘There has been a brouhaha about this show, watch it and send in your opinion.’ Never mind freedom of speech, freedom of recommendation is under threat.”

Gilliam has made his feelings clear before now on social media – where he described it as sad that the Old Vic “allowed itself to be intimidated” and denounced the Old Vic 12 as “close-minded, humour-averse ideologues” – but this is the first time that he has spoken to the press about the affair. Although he’s trying to tread carefully, he hides neither his exasperation at the “absurd situation” nor his disdain for the attitudes of the Old Vic 12 and their ilk.

“I think they’re very righteous in their thinking and their thinking is very limited,” he says. “They think they’re doing something important, and they’re the future. They may well be, and I won’t be, that’s the simple fact.” He gives a mock wave: “I’m happy to say ‘Bye-bye kids, good luck!’ and hand over the keys. When the children rule, be careful!”

He won’t go quietly. After all, he says: “I’m in a position where I can afford to put my head above the parapet.” Maggie Weston, the Bafta-winning make-up artist who is Gilliam’s wife of almost 50 years and the mother of their three children, often urges him to keep his mouth shut, “but I just shout louder, because I believe in thought! Ideas, discussion and argument are what makes for a stronger society and if you can’t do that, if people are frightened to participate, then we’re f-----. I really do believe that.

“I think there is fear in the world right now. People are frightened to speak, and to think. And I’m not happy when intelligent people won’t speak because the atmosphere is so poisonous.”

In their 1970s heyday, the Pythons – John Cleese, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Graham Chapman, along with Gilliam – were such a cohesive team that, as Gilliam says, “you couldn’t tell who had written what, we became so connected”. When the Old Vic story broke, did any of the surviving Pythons rally to offer Gilliam their support? He cackles. “Nobody came forward! But the most interesting thing was Cleese.”

That week, art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon had hit the headlines after impersonating Hitler during a talk at the Cambridge Union. “It was a comic moment, a little Hitler joke, and he got blacklisted,” says Gilliam.

“And then the next day John, who had been invited [to the Cambridge Union], blacklisted himself because he’d played Hitler in one of the Python shows. The madness of that... Come on! It is bothersome that jokes aren’t appreciated now. How can we have got to that point?”

That the culture wars should be raging in the UK of all places particularly saddens Gilliam, who came to England in 1967 specifically to escape the conformist, confrontational climate of the States, later renouncing his American citizenship, a process completed in 2016. “This was nirvana for me,” he says. “But now…”

Would he consider apologising for any of the remarks that have got him into trouble? Apparently not. “When I do interviews I’m playing around, talking, joking. I’m not on a soapbox, I’m not trying to proclaim a truth, just throwing out ideas. You say something and it’s a headline and then… boom! How do we bring back context and nuance into the discussion?”

As for #MeToo, “I said, ‘You’ve got to remember that Hollywood is full of adults who are ambitious.’ What’s contentious about that? A well-known actress friend of mine called me and said, ‘I agree with everything you say, but I’m frightened to speak.’ It makes me crazy someone so intelligent was intimidated. I’ve said Harvey Weinstein is a monster. I’m not saying there weren’t victims – there were. He’s being punished, as he deserves. But not everyone is a victim – there are also people who benefited from him.”

I ask what he thinks about the victory of Johnny Depp – a wonderfully hallucinating Hunter S Thompson in the 1998 film Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and something of a Gilliam regular – in the recent defamation trial against his ex-wife Amber Heard. Gilliam cuts to the chase.

“He married the wrong person; Amber was the wrong person for him. It’s very sad that a man at a certain age loses his way.”

He reaches for the opening lines of Dante’s The Divine Comedy: “ ‘In the middle of life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood…’ That’s Johnny.”

Gilliam’s own epic journey as an artist owes a fair bit to the serendipity of encountering Cleese in New York in 1964, when the latter was performing in Cambridge Circus, a lauded Footlights revue. They’d ride the subway together, the Brit abroad doing proto Ministry of Silly Walks “freaky movements”. When Gilliam moved to London, it was a steer from Cleese that got him work as an animator on the subversive ITV children’s show Do Not Adjust Your Set, where he met Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Eric Idle. The rest is comedy history, although it didn’t seem that way to Gilliam at the time. “We were just making each other laugh,” he says. “The fact others enjoyed it was the big surprise.”

Films have devoured Gilliam’s attention for half a century. Into the Woods marks his first commercial theatre project, although he masterminded two celebrated Berlioz productions for English National Opera: The Damnation of Faust, in 2011, and Benvenuto Cellini, in 2014. His co-director for those, Leah Hausman, is also collaborating on Into the Woods, as is John Berry, the former ENO chief who co-runs the production company making this show happen.

Back in the 1990s, Gilliam had been approached by Paramount to make a film version of Sondheim’s musical, “but I didn’t like the script”, he says. “It had been suburbanised. The magic had gone.” When he asked the studio why they wanted to make the film: “They said: ‘We saw [Into the Woods] on Broadway, none of us liked it but we thought we could do something with it.’ I thought: ‘Oh, Jesus Christ – that’s the world of cinema.’” A theatrical sigh. (An acclaimed Disney film, directed by Rob Marshall, would eventually materialise in 2014.)

Then, four years ago, Gilliam video-called Sondheim. “A brilliant mind, playful, ironic, naughty. We wanted to surprise him and he wanted to be surprised, because he had seen so many versions. Then he goes and dies on us. F--- him!”

Everyone within earshot gasp-laughs. As with the infamous moment in Monty Python: Live at Aspen, the 1998 reunion show in which Gilliam kicked over an urn purportedly containing the ashes of the deceased Python, Graham Chapman, you realise that his schoolboy instinct for courting outrage is undimmed.

His Into the Woods will feature a new framing device – approved by Sondheim before his death aged 91 last November, shortly after the Old Vic debacle – in which a girl plays with her toy theatre. “The muse was my six-year-old grand-daughter,” says Gilliam. “We start with how a child would imagine the stories. Children and madmen are the people that interest me most because they don’t see the limitations that other people apply to the world. I’m a champion of the imagination,” he adds. “It’s the only thing that makes life interesting.”

Gilliam describes his Into the Woods as “probably my last creative act”, and there’s a sense of coming full circle. “Living in Minnesota, in the countryside, near forest, there was no TV, just radio and books. The Brothers Grimm stories hooked me and there was a radio show called Let’s Pretend where they acted out fairy tales. So my worldview is based on Grimms’ fairy tales. It hasn’t changed. I see the world in fairy-tale terms. Into the Woods [concerns] the meaning of life; it’s a brilliant work but it’s normally performed in a merely entertaining way. What I love about fairy tales is that they’re disturbing, they’re dark. We’re bringing those elements to life.”

What else can audiences expect from his production? Gilliam is cagey, but his collaborators tell me more later. “It feels as if you’re in the middle of (Gilliam’s 1988 fantasy film) Baron Munchausen, right in Gilliam territory,” says Berry. Designer Jon Bausor has helped bring Gilliam’s cinematic bravura to the stage: “The most outlandish idea is that we want to crash it all down,” he says. And there will be video homages to Gilliam’s animations. “I’d say there are bits that are Python-esque,” Hausman hints, “in that he loves to turn something on its head – it seems to be one thing then becomes something else.”

Into the Woods, with its critique of the “happy ever after”, broods on death and loss. Bausor says that Gilliam is “very aware of his own mortality. He’s worried he’s going to drop dead any second, and yet he makes light of that.”

Gilliam does look worn out – behind him are years of battles, far more arduous than the Old Vic upset, to get Brazil, Munchhausen and Don Quixote to the screen – yet fans can take heart from the tantalising thought that he might yet have one last movie up his sleeve. “I’ve written one and we’ll see,” he says, as he shuffles out. “It’s about God deciding to destroy humanity for f---ing up his beautiful garden and only one person is trying to save humanity – Satan, because without humanity he doesn’t have a job!”

Gilliam once said: “If it’s easy, I don’t do it; if it’s almost impossible, I’ll have a go.” Does that still sum up his view? “Yes,” he replies. “Discovering new territory keeps you alive – but it kills you at the same time. So it’s a fine balance. Am I gaining in strength or being reduced?”

Another giggle, and he’s gone.

‘Into the Woods’ is at the Theatre Royal Bath (theatreroyal.org.uk), from Aug 17 to Sept 10

Yahoo News

Yahoo News