Tom Aspaul: ‘I’m trying to learn to be less concerned about what people think’

Tom Aspaul is thinking about the lessons he learnt after leaving London. “There are a lot of people out there who are really, deeply unhappy, but they’re just keeping up appearances,” the pop singer says. “Moving away, I’ve been able to see that for the first time.” If you’d told him a few years ago that he’d talk this way about the capital, he’d have scoffed. The 35-year-old initially moved there from the West Midlands to study architecture, before pivoting to songwriting. Some of his earliest collaborations were with Mutya Keisha Siobhan (the reformed original Sugababes) and Kylie Minogue. For a pop fan, it didn’t get better than that.

But with such highs early in his career, what followed was “disappointing”. Aspaul admits that he was unfocused in songwriting sessions and often turned up late. His publisher gave him the boot. Around the same time in 2019, his relationship came to an end, and Aspaul found himself slinking back home with his tail between his legs. Nearly three years later, he’s still there, speaking to me over video call ahead of the release of his new album, Life in Plastic.

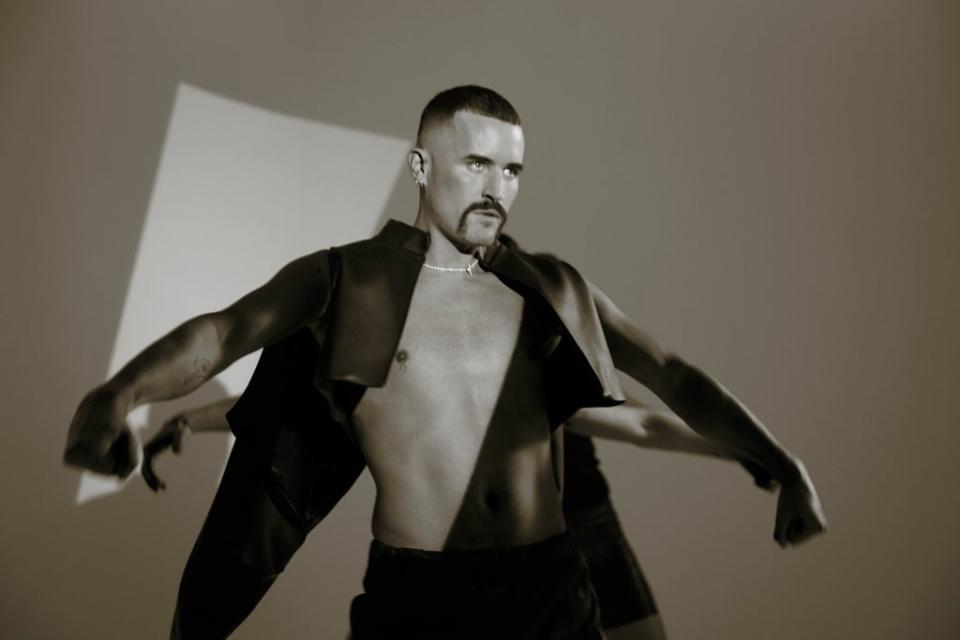

Mixing George Michael’s assertive sass with the surging synth-pop of The Human League, Aspaul’s music is unapologetically funky. His outfits usually match. Expecting to see the loud silk shirts, ornate matador costumes or eye-watering pink Speedos favoured in his album art, I’m surprised to find a far more relaxed Aspaul before me, sipping tea in an all-black get-up (still with his signature handlebar moustache, of course). But he is warm and candid throughout our conversation, which lasts long after his tea goes cold.

At first, Aspaul panicked about leaving the music industry behind. But as the pandemic took hold and the “s*** hit the fan”, in-person meetings turned to Zoom calls and he learnt to produce his own music and record at home. Without a major label’s backing, Aspaul has to be the manager, the agent, and the promotional team all in one. Yet on his own, he still managed to produce one of the greatest albums of 2020: the sparky “queer disco” record Black Country Disco. The other iterations of the pandemic’s dance-pop renaissance (Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia, Jessie Ware’s What’s Your Pleasure) might have enjoyed more commercial success, but Aspaul’s debut – with its tongue-in-cheek lyrics and rich Seventies sound – was every bit as good.

It was inspired by his mother’s favourite artists, including Chaka Khan, Prince, and Diana Ross. You can hear those influences on Black Country Disco, the glittering percussion of “01902” (a nod to the Wolverhampton area code) only a sonic step away from Anita Ward’s “Ring My Bell”. On “Carnelian”, Eighties synths and a pumping beat underscore painfully frank accounts of his own jealousy. Even when singing about heartbreak, Aspaul does it in style.

It was actually his homecoming that inspired the record. On the shimmering “WM”, he weighs up his home town’s ropey charm. “So we’re gonna take a ride on the Midland Metro/ Line 1, ’cos there’s only one line,” he sings on the bridge, before describing his love for both the “grey skies” and the “neon lights” of the city. It always fascinated Aspaul that his home town – a place he describes as “grim and industrial and depressing” – could have birthed Electric Light Orchestra, Slade and Duran Duran, as well as a thriving Black music scene. “Manchester and Liverpool, they’ve got such an incredible musical heritage as well, but you hear about that all the time… The Beatles and the Madchester music scene,” he says. “I thought that there wasn’t much of a championing of the West Midlands in general popular culture.”

On second album Life in Plastic, Aspaul explores a different side of his musical taste. In case the reference to novelty bop “Barbie Girl” in the title wasn’t enough of a hint, the record is an ode to the cheesy pop of the Nineties and early Noughties. The first sound you hear when you press play is the robotic gurgle of a dial-up tone. Aspaul lists Europop (he appeared on the UK’s Eurovision voting jury last year), Aqua and Steps among his inspirations, pausing to roll his eyes and murmur: “Yeah, Jesus Christ.” It feels obvious to compare Aspaul to Years & Years (namely because singer Olly Alexander is one of few British openly gay male musicians), but there’s a definite feel of the band’s sophomore record, Palo Santo, in the juxtaposition of bright instrumentation and dark lyrical themes.

Life in Plastic is a “pure bubblegum pop” record – but not without substance. It’s actually more like a jawbreaker: the shiny production is the hard outer exterior, but sit with it and you’ll find yourself in a “contemplative, dark, almost existential” world, in which Aspaul grapples with identity and the pressures placed on gay men. Yes, “Listen 2 Nicole” (as in Scherzinger) is a tune worthy of any pre-drinks playlist, but it’s actually an anthem about hook-up culture and finding independence.

Aspaul has concerns about people dismissing the album as a bit “naff”, explaining: “I was really worried it would be too camp, too bubblegum, too gay almost… I don’t think people would take me as seriously, as well, if I’d released this [album] first.” He pauses. “But I’m trying to learn to be a bit less concerned about what people think.” Music has always been Aspaul’s therapy, and never more so than on Life in Plastic. “I’m quite afraid of appearing vulnerable… so this is my way of doing it, burying it in the lyrics but presenting it as this really shiny, plastic, fun thing,” he says.

That doesn’t mean things are suddenly plain sailing. Being an independent artist gives Aspaul total control over his work, but it’s an expensive endeavour. His home is littered with vinyls of Life in Plastic he’s had to pay for up front, while filming the music video for lead single “Kiss It” left him “hardly able to afford to eat” for the rest of the month. He shrugs. “But that’s how it is.”

He doesn’t see himself staying in the West Midlands for ever, but there’s “no way” he could afford to work as a musician while paying London rent. “It’s a very sad state of affairs when artists are priced out of somewhere,” he says. “But I actually feel a sense of relief when I come home from London now. I’m like, ‘Get me on that train.’”

‘Life in Plastic’ is out on 30 May

Yahoo News

Yahoo News