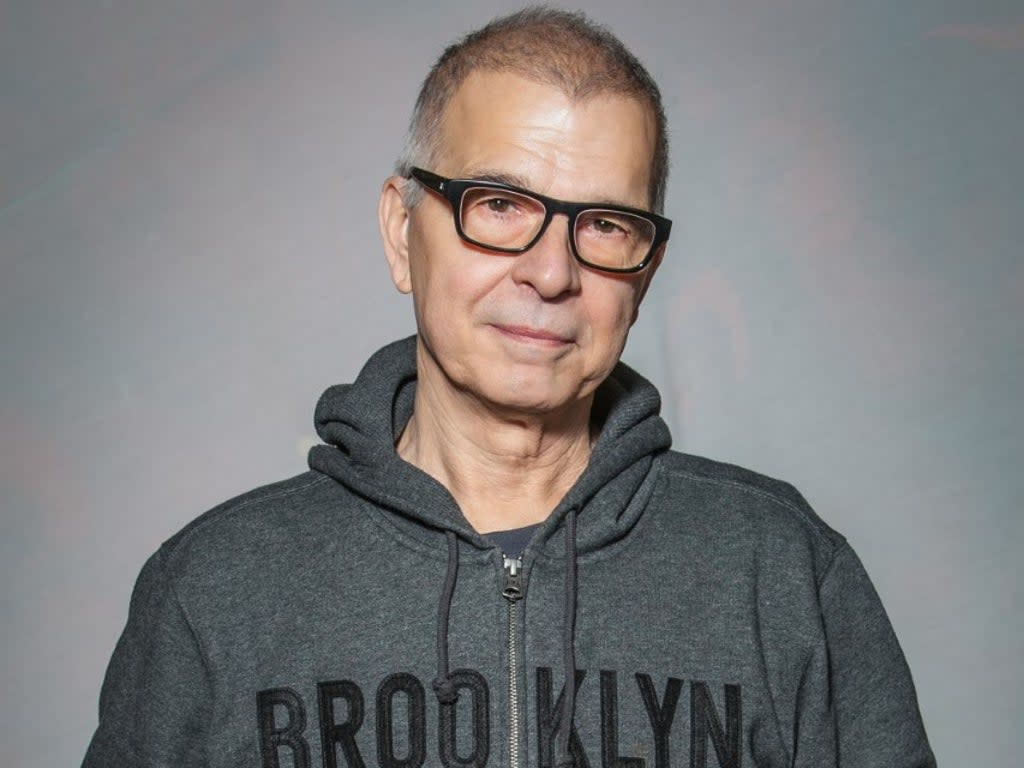

Tony Visconti: ‘Spotify is disgusting – it does nothing to support the culture of music’

I don’t know why you guys don’t vote Boris Johnson out,” says Tony Visconti. “We got rid of Trump…” The accusation hangs heavy in the air. “What’s your story?”

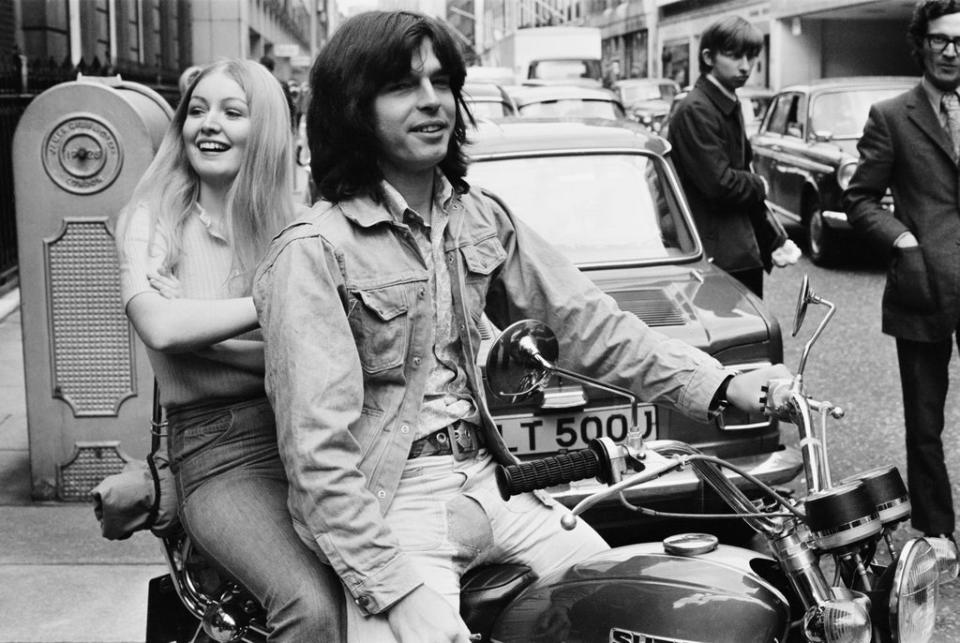

It would be easy to bristle at an American lecturing the UK about politics, but Visconti has more right than most. It was London where the renowned producer lived and worked for 23 years, and where he met David Bowie and Marc Bolan, with whom he helped shape the glittering glam-rock era of the Seventies. “It’s a typical political move,” he says of the prime minister’s removal of Covid restrictions in England this week. “So many people in the UK don’t like him – this is a little bone he’s throwing them to say, ‘OK, Boris is cool because I don’t have to wear a mask now.’”

Visconti’s camera is off – he’s in New York where he lives with his partner of 20 years, musician Kristeen Young. Yet the 77-year-old has a warmth and humour to his voice that makes it seem as though we’re in the same room. Despite his views on Johnson, he still admits, wistfully: “Half of my heart is in the UK.”

It’s not long before Visconti will be back there to tour with Holy Holy, his Bowie supergroup (not a tribute act, their website says sternly), for a Best of Bowie tour featuring English singer-songwriter Glenn Gregory and guitarist James Stevenson. Until two months ago, that lineup also included Woody Woodmansey, who performed with Bowie in his backing ensemble The Spiders from Mars. A statement released by the drummer in January disclosed a fallout with the band due to his “medical exemption” from the Covid-19 vaccine. “The band do not feel safe having me involved and have replaced me,” he said.

“We tried everything to make it work,” Visconti sighs. “The discussions started in December last year when [cases of the Omicron variant were] very high, there were loads of infections… it was very risky.” After Woodmansey left, Visconti says they offered him the job back when cases began to drop again in the UK. “He’s ghosted me,” he says. “I really am very sad about it, as other members of the band are, but we had to look after our own safety – we’re gonna be in dressing rooms, buses… we can’t afford to get sick.”

It’s strange to hear of Visconti falling out with anyone. As a producer, he’s famed for his ability to make artists feel validated in the studio. He also tends to only work with artists he believes he’s compatible with. Many of his working relationships have spanned decades, including the albums he produced with Bowie, from 1969’s Space Oddity to the musician’s final album, 2016’s Blackstar, released two days before he died. Visconti had only just landed in London in the late Sixties, apprenticing with British producer Denny Cordell, when he read an advertisement for Tyrannosaurus Rex playing at the UFO Club on Tottenham Court Road. A week later, Bolan was in his flat making demos.

Visconti brings an elegance, a kind of American glamour, to much of the music he produces, along with a spidey sense for innovation. He was responsible for the swooning symphonic arrangements heard on T-Rex songs such as “Cosmic Dancer” (1971), and for the pioneering use (or misuse) of the gating technique that led to Bowie’s impassioned vocal delivery on “Heroes”.

He speaks of both artists with great fondness, not just for their music and friendship, but for the ways in which they challenged societal norms of the day. “Bowie made it cool to be androgynous,” he says. “He opened the door for so many people living in secrecy and darkness over the years.”

Bolan, he notes, was perhaps “a month ahead” when it came to pioneering the glitter and satin-shrouded look of the glam-rock era, but Bowie was already experimenting with androgyny. “He thought, ‘Why do I have to look like a guy… I don’t wanna look like a woman either, why can’t I just be something else?’” he recalls.

He believes this attitude, the way Bowie challenged stereotypes surrounding gender and masculinity, helped make it possible for Sebastian – Visconti’s son with his third wife, former music executive May Pang (previously girlfriend of John Lennon) – to come out as gay years later. “So it’s affected me on some level.”

Visconti shares small pieces of his family life with his followers on social media – old family photos, birthday dinners, his new grandchild – and plenty of opinions, too. In January, he tweeted asking his followers to help him delete his Spotify account. Does that mean he sides with Neil Young in the row over Joe Rogan’s controversial podcast? “I thought about it, but I use Spotify as a tool,” he says, and I can almost hear him shrug. In the end, he didn’t delete it. “You can’t start banning people because they have a different political view than you, and I think the truth comes out anyway. Once you start banning people and censoring them… it’s not free. You have to give people equal time and let others decide what’s the truth.”

I’m surprised, given the stance he took over his former bandmate. “If it’s a physical threat, you have to make a choice,” Visconti says, calling the situations “totally different”. “If it’s people shooting their mouths off, so what? Turn it off!”

You can’t start banning people because they have a different political view than you

Tony Visconti

He does, however, support the off-shooting debate surrounding Spotify, about the pitiful amount they pay artists per stream (£0.002 to £0.0062). “Spotify is disgusting, the money they make out of [artists],” he says. “If you had 12 million streams, you could barely afford lunch for two people. It’s ridiculous, I don’t know why it’s allowed. Spotify does nothing to support the culture of music.”

It’s something else that Bowie foresaw, having once claimed that the way we listen to music would become similar to the way we consume water or electricity. “He was really ahead, he understood the concept of the internet before most people did,” Visconti says. “He was a visionary, and you’ll find many things he said that have come to pass.”

Visconti shares Bowie’s apparently ceaseless desire to create. He’s appeared on the credits of at least one album every year for the past 50 years, from albums by Bowie and Bolan to Sparks, The Stranglers, Iggy Pop, The Moody Blues, Manic Street Preachers and, in 2019, The Damned’s first album in a decade, Evil Spirits.

After the Best of Bowie tour, he’ll stick around in London to work with Irish designer and artist Daphne Guinness, on her fourth album. He sounds excited to be moving around again, but wary of the ways in which social behaviours have shifted during the pandemic. “It’s a new world – we developed some bad habits during lockdown,” he says. “A lot of people are angry.” He thinks we lost “a little bit of civilisation” during the pandemic. “The anger is so strong,” he says, slowly. “We just have to get over it.”

The Best of Bowie tour is from 2 March

Yahoo News

Yahoo News