The Wham! in China documentary George Michael didn’t want you to see

“The whole Wham! in China episode went from farce to disaster,” Lindsay Anderson wrote to a former colleague in March 1986. The fêted director of If… and This Sporting Life was even more forthright in another letter to workmates. “I was not prepared for the incredible waste, silliness, lack of conscience, ignorance, lack of grace, lack of scruple, egoism, weakness, duplicity and hypocrisy which have characterised the whole operation,” Anderson wrote.

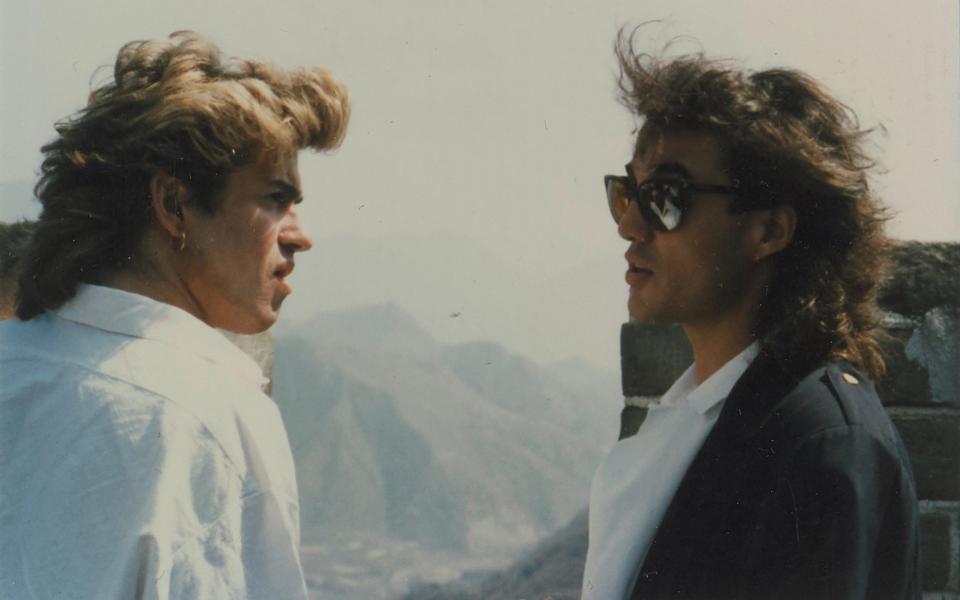

The “operation” in question was a proposed documentary about pop group Wham!’s concert tour of China in April 1985. George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley were the first Western pop stars to play in the country, and they’d hired 61-year-old Anderson to make a film about it. But, as Anderson’s letters make clear, it descended into chaos and sparked one of the most intriguing and catty artistic fallings-out of modern times.

Anderson’s film was rejected by the band and he was fired. His cut has never been seen in public and can only be viewed by appointment at the University of Stirling, where the director’s archive is kept. To mark the 40th anniversary of Wham!’s debut single Wham Rap! on June 16 – and as an extended version of the 2017 documentary George Michael Freedom Uncut comes to cinemas later this month – I went to Stirling to watch the film and delve into Anderson’s personal letters.

It was a bizarre mismatch from the off. Michael and Ridgeley, then 21 and 22, were pop’s good-time boys; image-conscious, adored and wildly successful, their last five singles had topped the charts in either the UK or America or both. Anderson, meanwhile, was a Palme d’Or-winning feature film director who in the 1950s had co-founded the Free Cinema documentary movement, which specialised in the unrushed realism of everyday life. The shoot itself was beset by problems. Early on, Anderson injured his leg at the Great Wall of China and was confined to a wheelchair. A large travelling press pack made the band’s life miserable.

Anderson’s 80-minute film, called If You Were There (after the Wham! song), is a ruminative and respectful take on the band’s time in China. Rather than simple pop promo, the film reflects an interesting culture clash: the mutual bemusement when a colourful Western pop juggernaut lands in a closed society for the first time.

As well as footage of Wham!, it features arms-length shots of Chinese street scenes, sunsets and traditional pastimes. It’s big on East meets West juxtapositions: footage of a quiet temple segues into Wham! singing Everything She Wants dressed in brash faux-military white uniforms with vast epaulettes. The song is intercut with shots of Western appliances in Chinese shops to demonstrate creeping modernisation (fans at the concerts were all given free Wham! cassettes).

In another scene, the band watches in horror as a snake is skinned alive in a restaurant, and there’s a stilted garden party at Beijing’s British embassy. There are touching moments too, such as when the pair – who genuinely try to cope with the maelstrom around them – write a speech in the back of a car en route to an official banquet. “Pad it out with loads of words,” says Ridgeley. “We’re deeply honoured and greatly flattered,” suggests Michael. “Greatly flattered?” replies his bandmate.

But the film also captured an ego clash: when an auteur’s attempts are crushed by the very pop juggernaut that hired him in the first place. Anderson, who died of a heart attack in 1994, realised Wham! weren’t happy with the footage soon after returning to the UK. Initially he dealt directly with Michael, who died in 2016. In a June 1985 letter to the singer, the director said he wasn’t surprised he didn’t like the rushes (“I can well imagine that it was a depressing experience”). But Anderson urged Michael to have faith, saying there was some “interesting and original stuff” there.

“I don’t guarantee that Wham! in China! [as it was then known] is going to be a classic. But my guess is that it will be more than respectable,” Anderson wrote. In another letter, Anderson adopted an artist-to-artist tone and played the avuncular older statesman taking the young buck under his wing. In an attempt to create an ‘us versus them’ narrative, he told Michael that Wham!’s managers Simon Napier-Bell and Jazz Summers “don’t really understand the creative process.” He added that the men “seem to be terrified of you”, whereas he himself had “enough respect for your creative sense and intelligence not to be scared to show you the work.” The letters came to nothing.

Anderson had warned Wham!’s management that his 80-minute film was “certainly not just a film for teeny-boppers”. But a film for teeny-boppers, stuffed with heart-melting shots of their idols, was precisely what the Wham! camp wanted. In October 1985, Anderson was sacked and his editing team resigned.

Battle lines were drawn. Dave Myers, the film’s director of photography, told Anderson he was “outraged and disappointed” by events. “You were subjected to such a manipulative power trip,” he wrote. In his reply, Anderson argued his film was one of “originality, charm and quality.” Now a director scorned, Anderson backtracked on his apparent respect for Michael, “Of course George Michael, though talented in his very limited range, is a spoiled, conceited dumbbell. But I really think it was the malice of Simon Napier-Bell, with his endless appetite for destructive intrigue, which influenced George to order my removal from the film.”

Speaking from his home in Thailand, Napier-Bell refutes this version of events. He says it was Michael who wanted to ditch Anderson. Napier-Bell had known the director since childhood as his father Sam was also a director and they’d worked together. “It was acutely embarrassing because I’ve known Lindsay since I was five years old and I was told to go and fire him – but I made Jazz do that,” says Napier-Bell.

But the reason for the sacking was clear. “He hadn’t made a film with any deference to who was paying him and why they were paying him.” Napier-Bell says Anderson “wanted to do it as if the BBC said to him, ‘I hear this band Wham! are playing in China – go and get the real story.’ But he’s working for Wham!” Put this way, you can see his point.

“It’s no good being arty about it. Wham! needed a film which showed them going to China. It cost us a million pounds of Wham!’s money to go there,” Napier-Bell says. He claims Anderson portrayed the pair in a bad light, and that they found the film boring. He said Anderson threw a “complete tantrum” on learning this latter fact. “He said, ‘How can you work with these people?’ I said, ‘Well, how can they work with you? It goes both ways,’” says Napier-Bell. He adds, with affection, that the pair “behaved like two young millionaires with a fuddy-duddy old Left-wing fart. He got what he deserved.”

Enter Michael Winner. The Death Wish director wrote to Wham!’s management in October 1985 about the “unfortunate fracas” in his capacity as a member of The Directors Guild of Great Britain. Winner urged them to let Anderson finish the film. Anderson thanked Winner for his help in a letter which contained another broadside against Michael, who was described as “a classic case of the shivering aspirant plucked out of the street, who turns almost overnight into a tyrant of fabulous wealth.”

The film was radically recut by filmmakers Andy Morahan, who’d directed Wham!’s pop videos, and Strath Hamilton. They used some of Anderson’s footage, and added scenes including Michael having a table massage. The Chinese concert footage was reshot at Shepperton Studios (according to Anderson, Michael had had a haircut since returning home so wore a wig). A shortened, poppy version – renamed Wham! in China: Foreign Skies – was premiered at the band’s The Final concert in Wembley Stadium in June 1986. Despite everything, Anderson was billed as “director”.

Karl Magee, archivist at the University of Stirling, says that Anderson’s cut remains unreleased due to an agreement between the University archives and the film’s rights-holders. But he explains why the original film is so culturally valuable.

“It’s the unseen Lindsay Anderson film. A last major documentary he made. In a sense this was his last Free Cinema film – in the way he treated the subjects and moved the camera away from Wham! and started looking at China,” says Magee. “Although he was not really following the brief he was given to make a pop promo.” This much is true. But rarely has a clash of egos and creative sensibilities been so grippingly entertaining. This was a battle royal between high culture and pop culture. And pop culture won.

George Michael: Freedom Uncut is in cinemas from June 22

Yahoo News

Yahoo News