Jamie Vardy hardly touches the ball for Leicester - why is he so important to Brendan Rodgers' style of play?

In 2014/15, Jamie Vardy scored five goals in 34 Premier League games. Other than a few fortunate punters, nobody could have predicted Leicester's title win the following year or that Vardy would become one of the division's most clinical strikers, smashing the ball into the back of various nets 24 times in 36 matches that season.

We've been through this before, but an interesting aspect of Vardy's continued goalscoring form four years later at the age of 32 is that he hardly ever touches the ball - how can a striker influence play so often without getting near the thing he needs to score?

This season, Vardy averages only 20 touches of the ball per game. In context, teammate James Maddison has 67.5 touches per game while Spurs' Son Heung-min has 56.75.

Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang is a similar sort of player, often found lurking off the shoulder of the last man and rarely seen linking play anywhere near the midfield, but even he averages 39 touches per game.

Marcus Rashford gets 41.8 touches per game, Sergio Aguero has an average of 32 touches per game, Tammy Abraham 24.8 - only Norwich's Teemu Pukki comes anywhere close to Vardy's lack of involvement with 23 per match as a comparable player. However, despite having no direct impact in Leicester's passing, Vardy is absolutely integral to the team.

Brendan Rodgers plays a possession-focused 4-1-4-1, a structured shape that defends as a 4-5-1 and attacks with four interchangeable forwards behind a striker, supported by the full-backs.

Vardy's job is to stretch the opposition defence and create depth, standing as far up the pitch as he can get to create distance between defence and attack. Scared by the threat of Vardy's pace, defenders have to drop deeper than they might like to ensure they aren't beaten in a race and this gives Leicester an out-ball over the top, something which created their opening goal in the 3-1 win over Bournemouth.

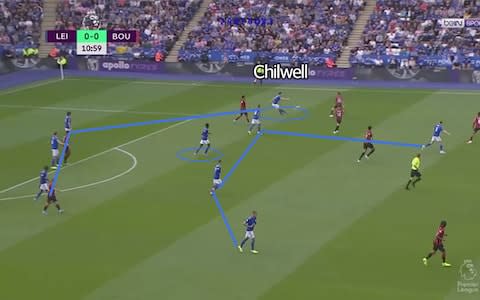

After surviving a spell of heavy Bournemouth pressure and with Leicester transitioning back to their 4-1-4-1 shape (Wilfred Ndidi is the midfield '1', circled below), Ben Chilwell looks for a forward option rather than slow build-up near his own box.

Vardy had already started a run beyond the centre-backs, who were left isolated due to Bournemouth players pouring forwards in the earlier move.

Neither were fast enough to get close to Vardy, who spotted Kasper Schmeichel off his line and lifted a brilliant first time volleyed lob over the goalkeeper's head.

Opposition teams are aware of this threat - Vardy has been doing it for years now - but once he's at full speed, it's very difficult to prevent. Besides which, with an average of 54.82 per cent possession, it's usually Leicester who are in control of the ball, which is why Vardy's selfless movement makes all the difference.

Leicester's four attacking midfielders - usually Harvey Barnes, James Maddison, Youri Tielemans and Ayoze Perez - work in space between lines of opposition defenders. To allow the likes of Maddison and Tielemans room to create, Vardy pushes the centre-backs ever deeper to increase distance between them and their midfielders, thus generating space.

With Maddison on the ball, Vardy has an expert chance-creator to make runs off. Maddison has created 11 chances this season, and though this ratio of 1.83 per game is lower than the 2.79 created per game last season, it's almost certain to be similar come May - Maddison was statistically one of the most creative players in the league in 2018/19.

Some strikers get bored when not involved and start roaming ever deeper to get on the ball - Harry Kane is a prime example of that this season - but Vardy constantly maintains his position high up the pitch. If he were to come looking for the ball in midfield, Leicester's shape would lack the verticality needed to open up areas for others.

A more static striker like Kelechi Iheanacho, who tends to poach on second balls, or even a target man like West Ham's Sebastian Haller, would not offer the same threat since defenders can set a line and squeeze up, unperturbed by a lack of movement in behind. Vardy's diagonal runs between centre-backs makes an offside trap difficult to execute accurately though and this forces one defender to drop slightly deeper behind his partner to track him. All these subtle runs are for the benefit of the team - Vardy's presence, speed and cunning creates space for others.

Possession based teams can often be led down an alley by a defending side's press. If you push the ball wide you can then block that space and show the play back inside, repeating until a turnover can be won. Claude Puel's Leicester were guilty of falling for this trap, averaging 430 passes per game with 49.3 per cent possession, playing laborious predictable football that opposition teams had little trouble in slowing down.

Rodgers has upped Leicester's retention of possession to 54.8 per cent since taking over and has them playing more passes too (507 per game), but has made the side far more dangerous in attack by making the pitch bigger more urgently.

The full-backs provide width by overlapping the wide forwards when able, but in earlier buildup the wide forwards hug the touchlines.

That all four of the players across this line can interchange positions is essential. Marc Albrighton is a central midfielder in this screen grab as Tielemans takes up the wide right position. All four are stood in the space between Bournemouth's defence and midfield as Ricardo Pereira brings the ball out from the back, and because Leicester have players on either touchline, the Bournemouth back four has to open up to cover. That gives the central midfielders more time and forward options when on the ball and also creates more room for Vardy to make runs in behind.

Leicester's defence is key to this all working too as without adequate cover, Rodgers' players could afford to open and play this expansive style of football, which shares far more in common with Pep Guardiola's Manchester City than Claudio Ranieri's title-winning Leicester.

Ndidi is the under-appreciated driving force of the team and holds everything together as the anchor, protecting the defence by winning the ball in space just ahead of them and kick-starting counter-attacks.

Ndidi's player radar last season was reminiscent of N'Golo Kante at his Chelsea best (the below is from the 2018/19 season) though is perhaps more impressive defensively because of Kante's advanced position under Maurizio Sarri.

Leicester's excellent full-backs certainly help as does the partnership between Jonny Evans and Caglar Soyuncu at the back. Rodgers has one of the most balanced starting XIs in the entire league and it should be no surprise they sit in third place ahead of the weekend. Where other teams like Manchester United have clear deficiencies, Leicester have stability and optimism and that is highly relevant this season.

Just as Ranieri took advantage of a weak top four to pull off Leicester's miracle title win, there is a power shift in the Premier League open to be exploited. Chelsea, Tottenham, Manchester United and Arsenal are not the same beasts as in previous years and there are two slots below Manchester City and Liverpool which can be stolen from the traditional elite.

If Leicester were to manage that feat, it would be no act of theft. They are entirely deserving and capable of a Champions League spot on current form, have one of the best midfields in the league and have a clear on-pitch style that is yielding results. Everyone has their own role to play and Vardy, despite hardly ever seeing the ball, is one of the most important cogs in a machine quietly driving towards a pot on the podium.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport