‘Am I going to get shot?’ Comedy’s wild pranksters on their most daring stunts

It was the political prank so audacious you could hear the laughter, and the drawn breath, from the other side of the Atlantic: in May this year, within a week of the Uvalde school shooting, Jason Selvig of stunt-comedy duo The Good Liars stood up at the National Rifle Association convention in Houston, Texas, fixed its chief executive Wayne LaPierre in the eye, and thanked him for all the “thoughts and prayers” his organisation had offered over decades of mass murder. “If we give enough of these thoughts and these prayers, these mass shootings will stop,” deadpanned Selvig, as LaPierre faced him down with a gimlet stare. The gun-lovin’ crowd shifted awkwardly in their seats.

Here was a prank for the ages. But also one to make you wonder: whither the great British prank, as practised with distinction by the Mark Thomases and Chris Morrises of yore? Or by Sacha Baron Cohen, who recently successfully defended a $95m lawsuit against a Republican ex-senator identified by a “paedophile detector” on Baron Cohen’s 2018 show Who Is America? We have Joe Lycett, of course, heroically changing his name to Hugo Boss and leaking spoof Sue Gray reports to a panicked parliament. But “we need more of them,” says Simon Brodkin, one of the art form’s celebrated exponents. “We need them when anyone starts taking themselves too seriously. Who the hell wants pomposity ruling the world?”

We got flung against walls. Our picture was circulated by naval intelligence

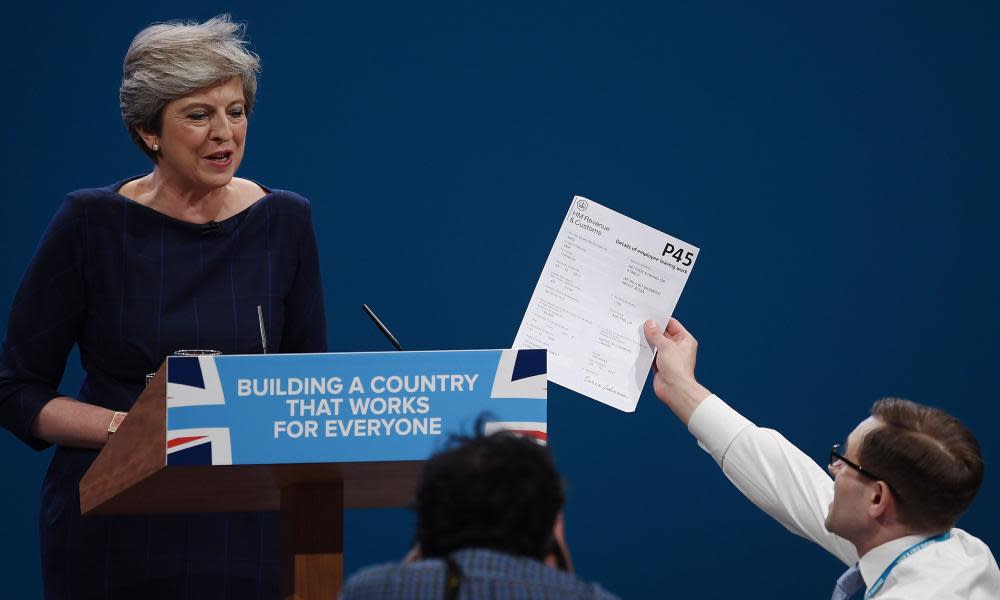

Brodkin has now hung up his pranking boots, and refocused on standup with his new show Screwed Up at the Edinburgh fringe. But in his practical joking pomp, he once made life very uncomfortable for Theresa May, whom he served with a P45 at Tory conference; Donald Trump, on whose behalf he distributed Nazi golf balls at the then-presidential nominee’s Turnberry course in 2016; and Fifa president Sepp Blatter, showered in dollars by Brodkin at a 2015 news conference. They were heady times, says Brodkin. “For a while, I was one of the few people on the planet who, when they got arrested, was thinking, ‘That’s gone exactly as I planned!’

“The best stunts or pranks are where you are inserting your comedy into a very serious area,” he says now. “And what is more serious than politics? What is more serious than a prime minister?” It’s an extraordinary form of comedy that can fast-track you to front pages – or a prison cell. “You don’t want to be wired up normally to do these things,” says Brodkin. “You need absolute single-minded determination. There are so many challenges and so many ups and downs. You have to think: ‘Am I going to get shot here?’ So you can’t go in half-hearted.”

By way of example, Brodkin cites the elaborate preparation required for his stunt at a Geneva motor show in 2016. Volkswagen had recently been exposed as cheating emissions regulations; Brodkin, dressed as a mechanic, interrupted the company’s CEO as he addressed the world’s press to attach a “cheat box” device to the display vehicle on stage. “There followed 10 or 15 minutes of security roughing me up. The police were convinced I was an Islamic fundamentalist trying to blow up Volkswagen’s latest car.”

Jolyon Rubinstein can match that: “We had frequent run-ins with the secret service attaches to the PM and deputy PM,” he says. Rubinstein, with Heydon Prowse, played practical jokes on politicians, corporations and other deserving targets on the BBC’s Bafta-winning The Revolution Will Be Televised, from 2012 to 2015. “We got flung against a number of walls,” he recalls. “Our picture was circulated by naval intelligence, which was quite a thing. It was a huge rush. The adrenaline was unreal.”

Rubinstein and Prowse were Britain’s Good Liars for a while: a double-act who were one part comics to two parts activists. Brodkin defines his pranks as comical first and foremost: “It’s about the real world and the comedy moment colliding.” Whereas for Rubinstein and Prowse, who gatecrashed arms fairs and EDL marches, and asked David Cameron to autograph their Bullingdon Club photo album, it was about: “meting out comic justice to people who seem untouchable. But they’re not beyond reproach, and there needs to be a levelling of the playing field. It was always motivated by a sense of right and wrong. And the sense that people are getting away with it who shouldn’t be.”

Most of the great pranks we remember fall into this category. I’m thinking of the “culture jamming” social activism of celebrated US duo the Yes Men. Or the “made-up drug” cake, touted by Chris Morris on Brass Eye. Or Borat inveigling Rudy Giuliani into compromising positions. Or Mark Thomas (AKA “Thomas the prank engine”) getting an Indonesian general to admit that his country practised torture. “If journalism can’t hold power to account,” says Rubinstein, “then comedy must. I feel that very, very strongly. For the health of a democracy, that is profoundly important.”

There exists another genus of prank, of course, which eschews politics entirely. For every Revolution Will Be Televised, there’s a Beadle’s About. For every Chris Morris, a Noel Edmonds – news of whose supposed death Morris broadcast in another Brass Eye stunt, but whose Gotcha awards on Noel’s House Party featured a brand of pranking (hijacking a quiz on Dave Lee Travis’s radio show; funny business with Richard Branson and a hot-air balloon) that was more popular than Morris’s.

Into this lineage – “being silly, having fun, and putting a smile on people’s faces,” as he describes it – fits Max Fosh, a new prankster on the block brought to us by YouTube, and currently performing a fringe show too. But with Fosh’s work, there’s a twist. “I try to stay away from the word prank,” he tells me. “It has a negative connotation around there needing to be a victim. I don’t think people resonate with that any more.”

Fosh is speaking to me while journeying to remove the giant “Welcome to Luton” sign he constructed in May next to Gatwick airport. “The idea being,” he says, “to have a bit of fun with passengers thinking, very momentarily, they’ve landed at the wrong airport.” (Extensive media coverage followed, and 8m views on YouTube.) “Does that have a larger importance to the cultural conversation?” he asks. “No. It’s more of a timeline thing. You’re scrolling through, you see that someone’s written in massive letters ‘Welcome to Luton’ outside Gatwick, you get your two seconds of ‘that’s quite fun’, then you keep going.”

You might think it sacrilegious to bracket such comedy with the work of Sacha Baron Cohen. But there are affinities between these opposing species of prank-work. In both cases, the comedy exists only retrospectively. In the moment, the perpetrator experiences high anxiety and “the person having the stunt done to them,” says Brodkin, “generally isn’t seeing the funny side.” Fosh adds: “While I was setting up a massive tarpaulin in a field, I wasn’t sure it was going to be particularly funny.”

Both brands of pranking are largely male, too – not that anyone I speak to wishes to discuss the fact. (Brodkin: “Stop trying to get me cancelled, Brian!”) A reason for that gender bias may lie in the language its exponents use to describe the art form. “It’s like being a boxer,” says Brodkin, and later: “You probably need some good cojones on you.” Rubinstein, meanwhile, relates how he and Prowse racially profiled themselves: “We were two nice white middle-class boys who, once we put on a suit, could blend in with the status quo, pop out for comic effect, then vanish.” Blending in, and therefore pranking more generally, may be less easy when you don’t look like the powers-that-be. Fosh, incidentally, is an Old Harrovian.

At both ends of the pranking scale, too, there are ethical considerations. “I’m always thinking: might this be considered punching down?” frets Fosh. For The Revolution Will Be Televised, a code of ethics known as “the Revolution protocols” were drawn up with the BBC, recalls Rubinstein. “We always needed to present a framework to prove public interest. And we focused tightly on institutions, public figures or corporations we could demonstrate had done something [wrong]. It’s about choosing your targets,” he says.

No one in pranking needs to be reminded of what can happen when stunts go sour. In 2012, for example, two Australian DJs made a call to the Duchess of Cambridge’s hospital ward, pretending to be the Queen and Prince Charles. Their prank was followed three days later by the suicide of nurse Jacintha Saldanha, who took the call.

None of that diminishes, in Rubinstein’s eyes, the importance of pranking – in its political variety, at least – to the health of the nation. “We have a huge tradition going back to Swift of poking fun at public figures to make sure no one gets too big for their boots. The BBC and Channel 4 need to be braver right now in enabling those who have the gumption to put themselves in harm’s way.” Brodkin concurs: “How better to say what you think about someone than right to their face?” he asks. “Bring it to them. Let them know.”

“Mind you,” he adds, “most of the people who’re worth pranking couldn’t care less about what the world thinks of them. That’s the flipside. If you were pranking people who cared what other people thought of them, they probably wouldn’t be worth pranking in the first place.”

Simon Brodkin: Screwed Up is at Pleasance Courtyard, Edinburgh, until 27 August. Max Fosh: Zocial Butterfly is at Underbelly, Edinburgh, until 29 August