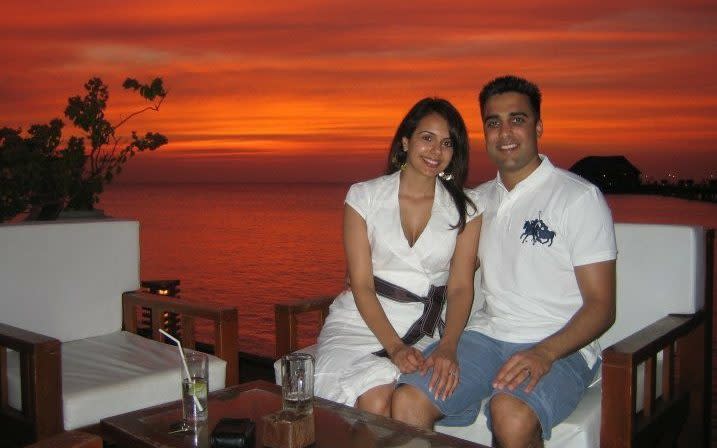

'Race never entered our minds': The heartbroken couple told they can't adopt a white baby

It is early on Friday morning, and if life had turned out slightly differently, there would currently be children scampering across the spotless new carpet in Sandeep and Reena Mander’s beautiful Berkshire home.

Plastic bowls and other toddler breakfast detritus would need to be cleared away in the kitchen. Upstairs, their four spare bedrooms would be cluttered with cots and toys. Instead, we sit sipping tea in the immaculate living room with their lawyer listening in – contemplating a silence they are desperate to fill.

This week, the normally intensely private British-born couple have found themselves propelled into the centre of a national storm, and over something as simple as wanting to adopt and raise a child of their own.

The Manders, both of whose parents came to this country from Punjab as children, have launched legal action against the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead and its adoption service Adopt Berkshire after being refused permission to adopt a white child because of their “cultural heritage”.

After failing to conceive naturally and undergoing a brutal six years of fertility treatments, the couple, who are in their early 30s and work in senior professional jobs, approached their local council to be considered for adoption. But they claim they were told that because the council only had white babies on its register they would not even be allowed to apply. Despite a year of campaigning against the decision and being backed by their local MP, Theresa May, the local authority is refusing to budge, prompting their legal action.

“We’ve always felt British,” says Reena, in their first newspaper interview since the story broke earlier this week. “When they refused us it was probably the first time I have ever felt different. This is my country. This is where I’ve been born and bought up. I can’t really identify with any other country being my home.”

Like many young couples up and down the country, Sandeep and Reena Mander first locked eyes over a sticky dance floor at a student nightclub. It was Reena’s first year of a business information services degree at Leeds Metropolitan University, where Sandeep was studying for a degree in business studies after finishing school in Maidenhead.

Theresa May wrote a letter in our favour, but the health authority didn’t budge

All of their parents had come to this country with nothing and worked hard to secure a better life for their children. Reena, whose grandfather fought for the British Army, was raised in Leamington Spa, where her father built up a successful haulage firm from scratch. She and her three siblings all went to university.

At Leeds, Reena embraced university life, playing lacrosse, netball and hockey alongside her studies, as well as taking part in student theatre. She was celebrating the end of her final exams in 2006 when she began to feel a pain in her stomach. At first she presumed it was due to having eaten some poorly-cooked chicken at a barbecue, but when the pain got worse she made several trips to the doctors. Eventually, she collapsed and was rushed to hospital in an ambulance.

“It was a cyst twisting on my ovary to the point where they had to perform emergency surgery,” she says. “If it had popped – which it was on the point of doing - it probably would have killed me. I lost one of my ovaries but thankfully it was after my last exams and didn’t impact me getting my degree.”

She was assured by the doctors that she would still be able to have children. Soon after her recovery, Sandeep booked a private “Cupid’s Capsule” on the London Eye and proposed, with all of London sprawling below them. They married in 2007, with a traditional Indian wedding in front of some 600 guests.

Although neither of them is particularly religious, they held the service at a Sikh temple in Leamington Spa and the reception afterwards at a hotel in Solihull. Sandeep arrived in the traditional Sikh manner on a horse - and then, in a nod to his British upbringing, ensured there was a Bacardi bottle on every table during the evening do.

Reena, 33, who is a senior project manager for the communications company Three, travelled to India to buy her array of outfits for the day. It was only the second time she had ever been to the country. “The first time I was five and I got bitten to death by mosquitos,” she says in her dry Midlands accent. “I’ve still got the scars now.”

The race of the baby never really entered our minds. We didn’t even discuss it between ourselves

Their plan was always to have children young – certainly before they were 30 - and about seven years ago they began trying for a baby. When nothing happened they visited a gynaecologist for advice and eventually were told there was no other option but IVF. Reena was around 26 at the time and excluded from NHS treatments, which at the time were unavailable to couples under 30.

When she finally reached that age, they were told she still could not receive NHS treatment as they had already gone private. This was the first time they enlisted the support of Mrs May. “She was very supportive,” says Sandeep, who is 35 and works as vice president of sales for a payments company. “She wrote a letter in our favour, but the health authority didn’t budge.”

In total, the couple had 16 rounds of IVF back to back using private healthcare both in the UK and Spain, where more donors are available. They estimate they have spent around £150,000 on treatments.

Then, two years ago, Reena finally became pregnant, only to miscarry at around 10 weeks.

“It was at that point where we had enough and couldn’t go through it again after that,” she says. “It can mean one or two things for a couple because it is such a stressful and emotional process, but thankfully it’s made us stronger.”

Instead, the couple registered their interest with Adopt Berkshire, the council’s adoption service, and in December 2015 attended an introductory workshop. They spent several months deliberating before deciding to officially register in April 2016.

“The way we’ve been bought up, the race of the baby never really entered our mind,” says Reena. “We didn’t even discuss it between ourselves.”

Sandeep says he was rejected outright because of his “cultural heritage” on the first phone call. The couple demanded a home visit by a social worker, but the council reiterated afterwards that they would not be allowed to apply. They claim they were told to adopt a child from India instead, despite having no close ties to the country.

Agencies are allowed to prioritise parents from the same ethnic group, but Government guidelines state that a child’s ethnicity should not be a barrier to adoption. The Manders’ lawyer, Georgina Calvert-Lee of the law firm McAllister Olivarius, says not even allowing them to join the register is a simple case of discrimination. Adopt Berkshire has refused to comment.

The Manders say their case - which is supported by the Equality and Human Rights Commission - is no longer about them. “The reason we are doing this [legal action] is to help other couples,” Sandeep says.

They have recently been cleared to adopt in the US, where Sandeep’s mother has family, and hope to be able to bring a child home soon. It is another expensive process, costing some $80,000 in fees alone.

The money, however, means nothing compared to the thought that they may soon be able to have a family of their own.

“When we have kids here it will be the happiest day of our lives,” Sandeep says. “I always keep thinking what I would do for them on the first birthday and what sort of party will we have.”

And then he breaks off, contemplating the future they have always longed for. And the agony of love as yet unfulfilled.