Badlands at 50: Why it’s still a killer film

It’s the dying fish that sticks in the mind. You don’t see one in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) or any of the other US movies about murderous young lovers on the lam. Director Terrence Malick’s astounding debut feature Badlands (1973), which started production just over 50 years ago, has a simplicity that is completely out of kilter with its time. While his contemporaries Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma were making gritty, violent urban movies exposing the racial, sexual, and political tensions in an America coming to terms with the disasters of Watergate and the Vietnam War, Malick was recreating the midwest of the late 1950s in loving fashion. Nostalgia reigned.

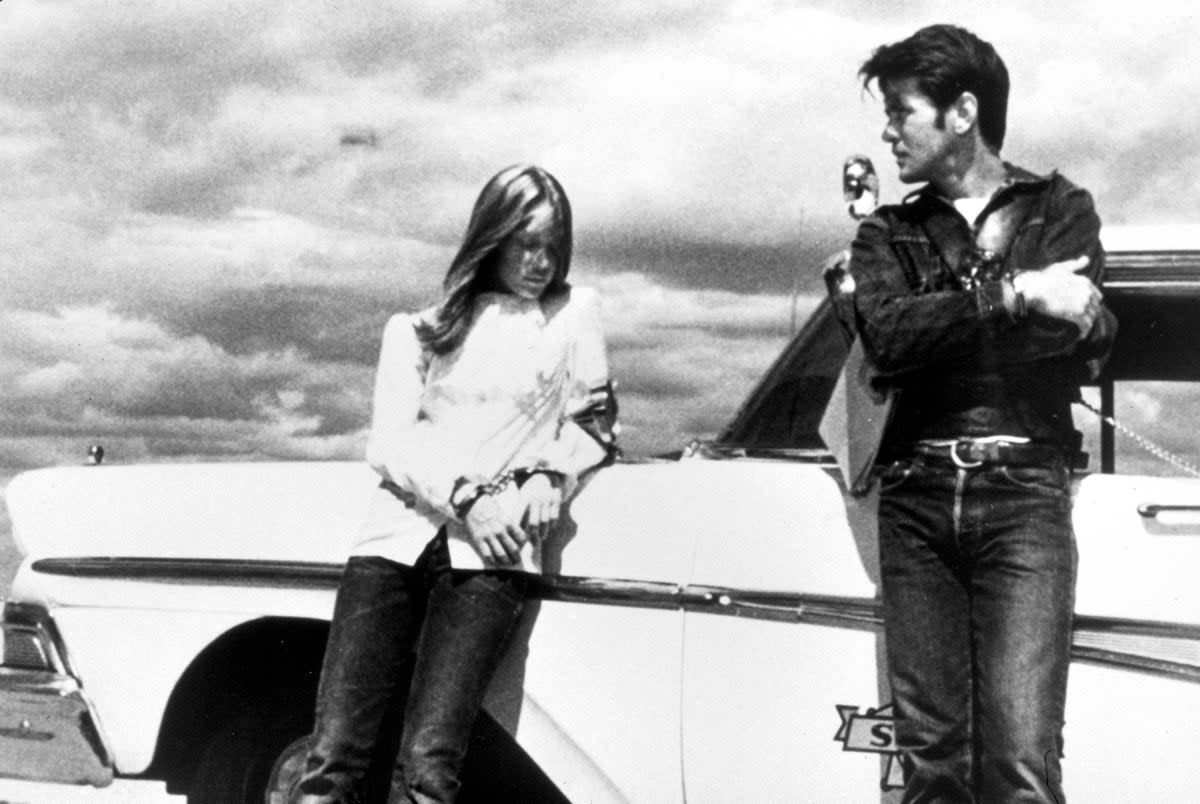

It’s not that Badlands skimps on the violence. This is a story about a serial killer who leaves corpses wherever he goes. In the film, the South Dakota garbage collector and James Dean lookalike Kit Carruthers (Martin Sheen) shoots almost everybody who crosses his path. However, Malick’s style is playful and naive. At times, it’s as if he is making a kids’ movie. That’s where the fish comes in. The first killing shown in the movie is committed by Kit’s doe-eyed teenage girlfriend Holly (Sissy Spacek). When her pet fish gets sick, she throws it out in the back garden. Malick includes a shot of the abandoned creature writhing away in the undergrowth, its gills flapping forlornly. He holds that shot for longer than he does any images of the bounty hunters, farmers, or passers-by who die at Kit’s hands.

The abandoned fish out of water is just one of the many oddball, surrealistic touches that run through the film. A little later, in an equally bizarre scene, when Holly’s father (Warren Oates) discovers she has been running around behind his back, he punishes her for deceiving him by shooting her dog. He then puts it in a bag and drops it in the river.

These days, Malick has a forbidding reputation. He is the Rhodes Scholar and philosophy lecturer who went on after Badlands to direct such daunting epics as The Thin Red Line (1998) and Tree of Life (2011). In his work, he has explored such subjects as war, the environment, religion, the cosmos, and the metaphysical mysteries of existence itself. Over the years, he has tried to re-invent film language, originating his own stream-of-consciousness style of storytelling on screen. Malick movies stretch your mind. They are beautifully made but tend to be very earnest and humourless affairs. He has also stopped speaking to the media, thereby accentuating the idea that he is some Prospero-like magus who exists outside the Hollywood system in a realm of his own. To his dwindling band of devotees, he is still a messiah-like visionary, but to his detractors, he seems obscure and pretentious. Critics seem to have forgotten, though, that his debut feature is as close to comedy as Malick ever came. It has a sweetness and whimsy that belies its themes – and it’s only 90 minutes long.

The film’s influence continues to be felt strongly today. Luca Guadagnino’s current Oscar contender Bones and All, starring Timothée Chalamet and Taylor Russell as young cannibal lovers on the run, owes it an obvious debt. Guadagnino emulates Malick in treating the most macabre subject matter in a lyrical and romantic fashion. Rock star Bruce Springsteen has long acknowledged his debt to Malick when writing his album, Nebraska. Generations of US indie filmmakers from Gus Van Sant and Harmony Korine to David Gordon Green have clearly drawn inspiration from Badlands.

Malick based his film loosely on the real-life case of Charles Starkweather, a high-school drop-out from Nebraska who modelled himself on James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause. In January 1958, Starkweather went on the rampage with his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate in tow, murdering 10 people over a period of nine days. He had committed one earlier murder a couple of months before.

Not that Malick was much interested in making a true crime drama in the vein of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. Nor does Badlands have much in common with films like Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, in which Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis play serial killers whose misdeeds are fetishised by the media.

“My influences were books like The Hardy Boys, Swiss Family Robinson, Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn – all involving an innocent in a drama over his or her head,” Malick told Sight & Sound magazine in a 1975 interview given just before he took his vow of omertà with the press. He said he wanted the “picture to set up like a fairytale, outside time, like Treasure Island”. The director even cited Nancy Drew kids’ detective stories as one of his key inspirations.

These are instructive remarks that go a long way in explaining why Badlands remains such a disarming experience. It’s light-spirited and playful when you least expect it. Audiences would normally expect to despise characters like Kit and Holly, but Malick makes us feel sympathetic toward them as if they are the victims.

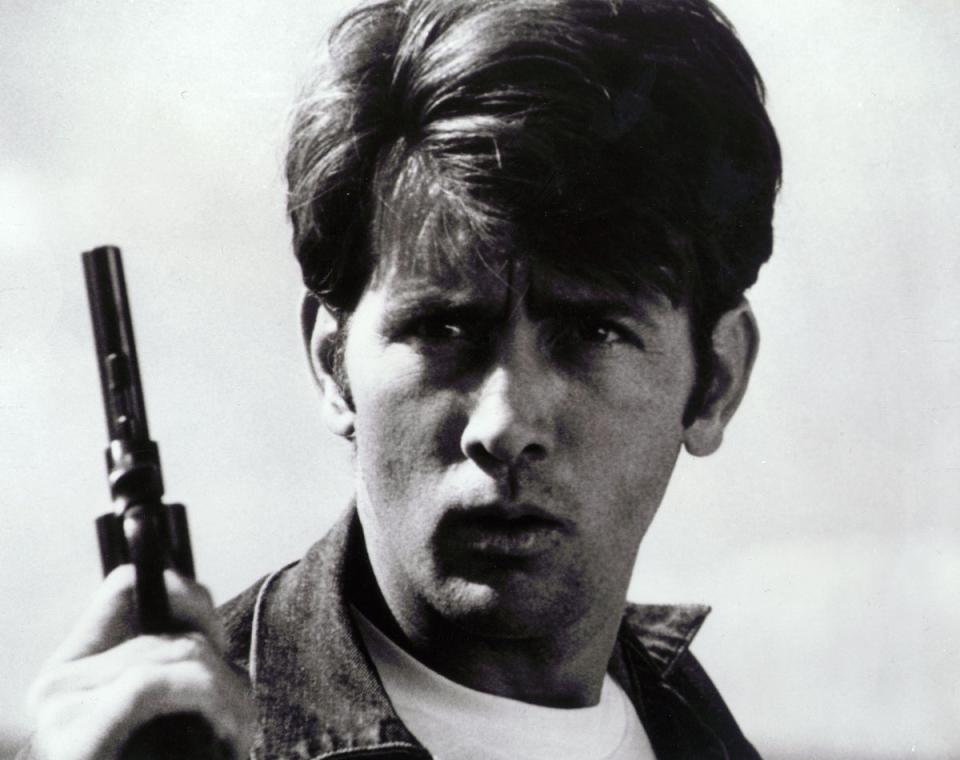

Sheen’s Kit treats his crime spree as if it’s a bit of a lark. He rarely shows anger or profound emotion of any sort. One of the few moments when he seems happy is when the cops tell him that he looks like James Dean. He basks in his own notoriety. We’re used to films in which criminals are dragged screaming and crying to the electric chair. Sheen’s Kit takes his fate in his stride. Holly tells us that he went to sleep in the courtroom when his confession was being read. His only real regret was that he didn’t shoot more people.

Sheen was in his early thirties when he made Badlands. Kit was supposed to be a much younger man. Malick cast him anyway. The fact that he was too old for the role added to the jarring effect he was trying to create. Spacek was in her early twenties, and not an obvious choice to play a high school-age teenager either.

Badlands was made on the hoof, without much money and with the crew sometimes close to mutiny. In his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, author Peter Biskind claims that Malick eventually ran out of cash “and continued shooting pickup scenes himself”. He also took a bit part in the film when there was no one else to play it. He is the architect who turns up at the rich man’s house where Kit and Holly are hiding out.

Biskind claims the voice-over from Spacek was added on in a last-ditch attempt to impose a semblance of coherence on a film whose plot was fast becoming incomprehensible. The narration, though, is one of the glories of Badlands. It’s quirky, poetic, and surprisingly witty. Spacek delivers it beautifully, in her beguiling sing-song voice, sounding as if she is Anne of Green Gables, although she is describing some very apocalyptic events. In her own quiet way, she is very funny. For example, when she is expressing her disappointment at her first sexual encounter with Kit, she says, “is that all there is to it?” Then at the end of the film, as if it is the happy ending she craved all along, she tells us: “Myself? I got off with probation and a lot of nasty looks. Later, I married the son of the lawyer who defended me.”

On set, Malick liked everybody to be on edge, never knowing what his intentions might be. In Absence of Malick, a short 2003 documentary about Badlands, Sheen recalled that on the first day of shooting, when he turned up “shiny, clean shaven and all spruced up”, Malick came up to him, apologised, reached down, picked up a handful of dirt and smeared it all over the actor’s head. Sheen didn’t mind. Although crew members were soon quitting in their droves, he was convinced that Badlands would turn out to be a “classic”.

Arthur Penn was famously inspired by French New Wave filmmakers when he made Bonnie and Clyde with its graphic but highly stylised slow-motion scenes of Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty being blasted to oblivion in a hail of bullets. Badlands was arguably the more subversive film. Its approach to death was casual in the extreme. Malick told Sheen early on that Kit’s gun was the equivalent of a “magic wand…someone gets in your way and, pouf, they’re gone”. When Kit kills people, even those he quite likes, he doesn’t have any sense of their suffering. Malick doesn’t judge his characters or try to explain away their actions in sociological terms. The film’s gentle, quizzical tone is set by the dreamy Carl Orff percussion music used on the soundtrack.

In 1973, Badlands was just a little too oddball for audiences. It did only modest business at the box office initially. Warner Bros, who were distributing it, seemed to lose faith in it. Some of the reviews were hostile. “Badlands is so preconceived that there’s nothing left to respond to,” the New Yorker’s Pauline Kael complained in a review that found the film as “flat and dead” as the landscapes it depicted.

However, Malick’s debut might not have been a commercial hit but it was greeted rapturously at the New York Film Festival where it premiered. As critic Richard Roud, founder of the festival, later remembered, the movie was “physically brought to us by an unprepossessing young man who turned out to be, not just a messenger as we thought, but the director himself.”

By then, Penn had already sent a letter to Roud telling him that he had seen parts of Badlands and thought it was pretty good. Bert Schneider, the producer of Easy Rider, had also tipped off Roud that he should keep an eye out for a debut feature by “one Terrence Malick”. By the time the film screened at the festival, there was already a cultish mystique surrounding Malick – and that mystique has continued to grow since then.

Fifty years on, the enigmatic US auteur is reportedly working on a bible epic called The Last Planet (but previously known as The Way of the Wind), starring Mark Rylance as Satan. As with most Malick projects in recent years, the film is shrouded in mystery. No one knows when/if we will ever see it.

However, the reputation of Badlands continues to grow. Justifiably regarded as one of the most striking debuts in cinema history, it is one of the US cinematic treasures now preserved in the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry. Amid all the reverence shown to the picture, what is still sometimes overlooked is the wry humour that Malick brought to his material. It’s easily his most accessible film, a good-natured yarn about a homicidal psychopath that is told in such a warm and folksy style that you half suspect its director must have had his tongue in his cheek all along.

‘Badlands’ is available on Prime Video