The best of 2020 in culture, from Parasite to Taylor Swift’s Folklore

Speaking to The Independent back in 2019, musician Jack White mused that perhaps there was too much freedom for artists these days. “I’m just saying that for a young artist, if no one else is putting restrictions on you, you should put those restrictions on yourself,” he insisted. “You have to make your own guidelines.”

Little did he know that a few months later, a pandemic would strike, and restrictions would be put on life and art like never before. But perhaps his sentiment stands: some of the entries in our lists of the best books, films, albums and TV shows of 2020 may not have existed were it not for lockdown – and certainly would not have been the same. Ali Smith’s wise and witty novel Summer, for example, and Taylor Swift’s Folklore, a surprise album full of infatuation and nostalgia.

Others, though, created before coronavirus hit, were a stark reminder of the art that can be made when people are allowed to rub up against each other, creatively, physically, emotionally – think of that final episode of Michael Coel’s dark, stark and unexpected I May Destroy You, or that nightmarish garden party in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite.

All of which is to say, great art will prevail no matter the circumstances. Here is the best of it from 2020.

The top 10 albums, as chosen by Elisa Bray, Helen Brown, Roisin O’Connor and Alexandra Pollard

10) Taylor Swift – Folklore

Taylor Swift’s 2019 album, Lover, was a return of sorts to her lush, romantic compositions of old. Those songs were visions of spring in pastel pink and purple, following the winter storms raging on Reputation. Folklore, then, is the hot ache of late summer, where infatuation and nostalgia thrive; the scent of woodsmoke and red wine hangs in the air. Written and recorded in isolation, it includes collaborations with Swift’s “musical heroes” – The National’s Aaron Dessner, Bon Iver, and her frequent songwriting partner and co-producer Jack Antonoff. There are no pop bangers here, just exquisite, piano-based poetry. (ROC)

9) Adrianne Lenker – songs

Both songs and instrumentals, Lenker’s two 2020 solo albums, had her so close to nature that she would lie in the dirt while recording. On “come”, the sound of rain pattering on the cabin roof they recorded in precedes the cold-water shock of Lenker’s eerie vocals, delivering stark lyrics like last rites. “Zombie girl” has windchimes and bird song, as Lenker evokes the gorgeous phrasings of Bonnie Raitt. Songs was created because Lenker was, as she puts it, “on a whole new level of heartsick”. It’s excruciating in its honesty – even for Lenker, who’s hardly known for shying away from her feelings. Now she bares her pain with complete abandon. It’s quite extraordinary. (ROC)

8) Sufjan Stevens – The Ascension

Sufjan Stevens was forced to leave much of his equipment in storage when a rat infestation forced him to move from his New York studio to the Catskills, where he noted the locals embraced a “stay positive/get the job done” philosophy. So lovers of Stevens’s quirky, literate lyrics will notice many songs on The Ascension orbit around cliches. The opening track is called “Make Me an Offer I Can’t Refuse”. Others are called “Die Happy” and “Run Away with Me”. As a huge fan of Stevens’s exquisitely personal and musically detailed 2015 album, Carrie & Lowell, I wasn’t sure I’d love the trippy new Macro sound. But I was rendered wonderfully weightless by a journey that delivers whole galaxies of nuance in a universal context. Trust me: the force is strong in this one. (HB)

7) HAIM – Women in Music Pt III

Best known for their sunny, classic-rock-indebted sound, the Californian Haim sisters have travelled a dark road to make their third album. So you might expect Women in Music Pt III to be a more difficult brew than the bubbling, amber festival beer of the band’s first two releases. But, while incorporating refreshing new sounds, it turns out to possess a surprisingly easy-going effervescent sound – reflecting the fearless fun the sisters were surprised to experience on releasing those uncomfortable feelings. This works best on depression-tackling tracks like “Now I’m In It” and the standout “I Know Alone”, whose murky glitches and neon pulses have the night-driving noir of The Weeknd in the rear-view mirror. Haim take us through a dark place and they do it frankly. But they never let the momentum dip. And they never lose sight of the light at the end of the tunnel. (HB)

6) Perfume Genius – Set My Heart on Fire Immediately

Over the years, Perfume Genius has honed a decadent and sensuous style of pop-rock. With trusted producer Blake Mills (Fiona Apple, Laura Marling), the artist born Mike Hadreas ensures that each and every note on his new album, Set My Heart on Fire Immediately, lands with devastating precision. These 13 tracks are finely wrought works of art that draw as much influence from Purcell and Mozart as they do scuzzy Nineties post-punk. On “Jason”, against the genteel camp of a clavichord, he adopts a motherly tenderness when faced with another’s inexperience and self-loathing. There’s a silver thread woven into each of these songs; Hadreas pulls and they move like a single breathing thing, just as bodies do when they’re pressed against each other, then released. (ROC)

5) Moses Sumney – Grae

Released in two parts, Grae branches into themes of masculinity, encapsulated by the propulsive “Virile”, where a satisfying contrast of textures incorporates a growling drone, soft flute and Sumney’s angelic vocals. When the album shifts into its second part, and turns inwards with a slower pace to match its vulnerable introspection, there’s no jolt: Sumney’s voice ensures that his soundscapes melt together. Flourishes of jazz flute and brass add warmth to “Two Dogs”, which showcases the acrobatics of his vocals as they glide effortlessly from falsetto vibrato to rich baritone. And the euphoric dreaminess of “Bless Me” – could there be a more heavenly gospel-cloaked crescendo on which to wrap up this astonishing feat? (EB)

4) Laura Marling – Songs for Our Daughter

Laura Marling’s previous albums have been grounded in evocative storytelling, her airy meditations on love, age and experience set against pastoral guitar landscapes. Not for nothing was she hailed, on more than one occasion, the voice of a generation. Subtler than her previous works, the music of Songs for Our Daughter is as fragmented and beautiful as stained glass.

By now fans are more than familiar with Marling’s virtuosic guitar playing and the way she can skip from twangy, Seventies Americana to the deft finger-picking of trad-English folk. “Lately, I’ve been thinking about our daughter growing old/ All of the bulls*** that she might be told,” she sings, as violins courtesy of Rob Moose (The National, Bon Iver) make this in part an elegy for her own experiences. What a marvel this album is. (ROC)

3) Waxahatchee – Saint Cloud

There’s always something tempering the beauty of Waxahatchee’s music. I mean that as a compliment: on the American singer-songwriter’s fifth album, Saint Cloud, luscious melodies are undercut by a lingering unease, sentimentality by steeliness.

The glorious “Fire”, which starts with plaintive keyboard strains, might have been described as “lovely” were it sung down an octave. As it is, with Waxahatchee (real name Katie Crutchfield) stretching to the upper limits of her range, her voice sounds like a match being struck. Her lolloping delivery on “Lilacs” – “and the lilacs drank the water/ and the lilacs die/ and the lilacs drank the water/ marking the slow, slow, slow passing of time” – is Bob Dylan by way of Lucinda Williams. On “The Eye”, which sounds like the sun rising, Crutchfield professes, “I have a gift, I’ve been told, for seeing what’s there.” For singing about it, too. (AP)

2) Dua Lipa – Future Nostalgia

Dua Lipa’s sensational second album Future Nostalgia channels the zingy, electro-ambitions of the 1980s with remarkable freshness, given that the decade’s revival has now lasted about twice as long as the original period. Her nods to Madonna, Olivia Newton John, Prince, Debbie Harry and Nile Rodgers are direct and unblinking – mercifully free from the raised eyebrow of irony so often used to give retro sounds a modern topspin.

She keeps a leather-driving-gloved command over the wonky synths of “Levitating” and “Hallucinating” and the spacey spangle glitter gel noises of “Cool” – on which she sings of “burning up on you/ In control of what I do/ And I love the way you move.” It’s invigorating to hear her use samples like barbells – lifting and flexing with them, not dancing around them like ornamental handbags. But I also love her use of the sexy-stuttering riff from INXS’s booty-call classic “Need You Tonight” on “Break My Heart”. You can picture whole families dancing to this together as kids’ and parents’ musical coordinates intersect. (HB)

1) Fiona Apple – Fetch the Bolt Cutters

Fiona Apple’s fifth album, Fetch the Bolt Cutters, is about “women”, she says, and “not being afraid to speak”. She never has been. Since she broke out with her debut album Tidal in 1996 – swiftly rejecting the industry’s sleazy embrace in the form of a scathing speech at the MTV Video Music Awards – Apple has made music that’s as fierce and mighty as a branding iron on fresh, white linen. Her songs have the sinister drama of a Sondheim musical, the technique of a classical symphony played backwards, and the titanic power of a pop song.

Named after a line uttered by Gillian Anderson in the BBC drama The Fall, Fetch the Bolt Cutters is no different. Manic descants, discordant pianos and abrupt changes in time signature at once complement and compete with each other in a carefully crafted clatter.

This is an album laced with defiance. Perhaps never more so than on “Under the Table”, on which she warns, “Don’t you, don’t you, don’t you push me”. “Kick me under the table all you want,” she smirks on the refrain. “I won’t shut up.” Good. (AP)

The top 10 books, as chosen by Martin Chilton

10. The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett (Dialogue)

Brit Bennett’s mesmerising gem about the Vignes twins, who disappear from a Louisiana farm town on a hot summer’s day in 1954, is a masterclass of moving storytelling. The Vanishing Half, which was shortlisted for Waterstones Book of the Year, is a thought-provoking assessment of race and social politics in post-war America. The powerful plot twists in the novel, which concludes in 1986, will keep you gripped until the end.

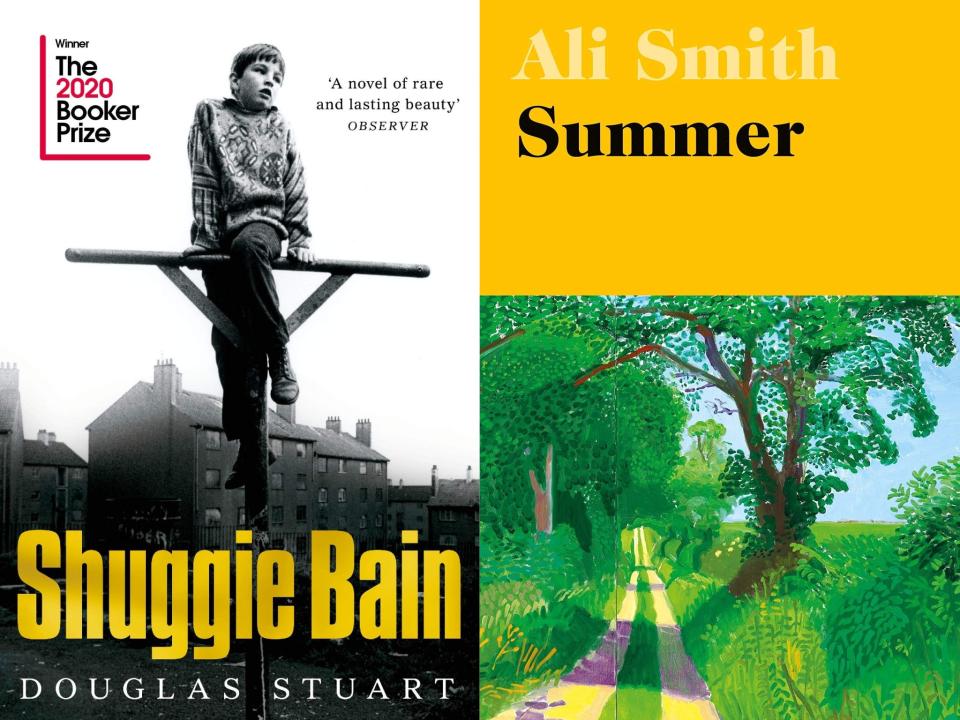

9. Summer by Ali Smith (Hamish Hamilton)

Ali Smith completed her ambitious seasonal quartet with the sublime Summer, which was started and completed during this gloomy year. Summer takes in the fractious events of Brexit, the global virus and the needless care home deaths, and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed the killing of George Floyd. The novel offers wisdom, humour and the hope of better days to come, including the uncomplicated joy of a beautiful summer afternoon in the English countryside.

8. The Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate)

Expectations were justifiably sky-high for the final instalment in Hilary Mantel’s portrait of Thomas Cromwell – which started with Wolf Hall (2009) and continued with Bring Up the Bodies (2012) – and although there was no third Booker award, Mantel’s concluding novel was another jewel of historical fiction. Her depiction of royal court intrigue is superb and full of relevance for our own craven times. The Mirror & the Light offered another illuminating portrait of Cromwell, and is also a complex, insightful exploration of power, sex, loyalty, friendship, religion, class and statecraft.

7. The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts (Doubleday)

The scope of history books was so immense this year that it was hard to pick a standout selection from a crop that included Matthew Cobb’s The Idea of the Brain: A History and The Hidden History of Burma by Thant Myint-U. The one that gripped me the most, however, was The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts, which is a stunning example of modern historical travel writing. The intrepid Roberts finds a brilliant way to summon a complex picture of Siberia through the story of how music found its way to one of the most remote places on earth.

6. Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu (Europa Editions)

In November, Charles Yu won the National Book Award for Fiction for Interior Chinatown, a satire about typecasting and racism in Hollywood. This inventive experimental novel, narrated in the second person and written in the form of a screenplay, captures the weirdness of existence and is by turns a hilarious expose of modern prejudice and a heartbreaking existential portrait of Asian American identity. It was like nothing else I read in 2020.

5. Broken Greek by Pete Paphides (Quercus)

Memoirs are tricky things to get right, and the best balance honesty with humour, acute self-analysis with perspective. I enjoyed autobiographical books by Deborah Orr, Ayad Akhtar, Hadley Freeman and Nicholas Royle, but the most enjoyable memoir for me was Broken Greek by Pete Paphides. It captures why the 1970s was such a weird decade and is also a loving testimony to the part music played in helping Paphides find a cultural identity. The book is also full of witty, authentic reflections on football, something you don’t always find when authors horn in on the beautiful game.

4. Apeirogon by Colum McCann (Bloomsbury)

Colum McCann’s transcendent book Apeirogon is fact-based fiction, telling the story of the unlikely friendship between Israeli Rami Elhanan and Palestinian Bassam Aramin, both of whom lost daughters to violence. McCann stitches together reflections on history, the nature of friendship, politics, the conflicting power of hatred and forgiveness, wildlife and art – turning them into a gorgeous tapestry. Booker-longlisted Apeirogon is about death and destruction, yet pain is part of what makes this book an essential hymn to peace and forgiveness.

3. Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell (Tinder Press)

Hamnet is set in an England devastated by a plague that kills the young son of William Shakespeare. Maggie O’Farrell deservedly won the 2020 Women’s Prize for Fiction for her profound, moving story of the boy’s death and the part this family disaster played in inspiring Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Hamlet. The ending to the novel is entrancing and O’Farrell’s meditation on the human experience is a triumph of imagination.

2. Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (Picador)

Although Shuggie Bain is a gloomy, brutal read, there is an underlying compassion and humour that make it an enriching one. It is also, at heart, a tender love story about a gay boy called Shuggie and his troubled alcohol-addicted mother Agnes. Douglas Stuart was the unanimous winner of the Booker Prize and his novel stood out by offering something so personal, so deeply seen and so overflowing with emotion. Glasgow, the setting for a story that takes place in the recession-hit 1980s, is its own glorious, anarchic character in the book. This is a modern masterpiece of humane storytelling.

1. Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss by Rachel Clarke (Little, Brown)

Bereavement and misery have been a constant in this troubled year of coronavirus death charts. Although it may sound strange, I found it helpful to read profoundly thought-provoking books about mortality, such as David Jarrett’s Meditations on Death: Notes from the Wrong End of Medicine. The book that bowled me over, however, was Dear Life by palliative care doctor Rachel Clarke. Although it is a painful read, because it forces you to reflect on some of the worst situations anybody ever has to face, the book is also a compassionate, wise gem, full of its own moments of sweetness. Clarke powerfully conveys the battering the NHS has endured over the past decade of austerity and false government promises, and her book should be essential reading for anyone who cares about our beleaguered health system. Dear Life was simply the most inspiring book I read in 2020.

The top 10 films, as chosen by Clarisse Loughrey

10. And Then We Danced

Levan Akin’s And Then We Danced is giddy with the pleasures of first love – how it pulsates through the body and mind. Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani) is a dance student at the National Georgian Ensemble, a young man with a sharp jaw and hungry eyes. He’s danced with the same partner, Mary (Ana Javakishvili), for years – the two are a kind of de facto couple. But his rigidly constructed world soon starts to crumble after the arrival of a new dancer, Irakli (Bachi Valishvili). This stranger moves with confidence. He’s muscular but light on his feet, with open features and an easy smile. Desire swiftly takes over.

Homosexuality isn’t outlawed in Georgia, but the country remains in the stranglehold of conservatism. Troops had to be stationed at the film’s few Georgian screenings, after ultra-conservative and pro-Russian protestors swarmed outside of the cinema. Akin’s film argues that joy can itself be a form of radical defiance. Merab’s story isn’t just about the pangs of desire, but the slow untethering from tradition’s pressures and expectations. He soon begins to explore his identity and his sexuality through movement: whether he’s out celebrating in the streets, partying to Abba, or seducing Irakli to Robyn’s “Honey”. To Merab, those dances are an act of reclamation.

9. The Assistant

In Kitty Green’s austere but devastating drama, we’re never told the identity of the cyclopean shape that cuts across the screen like a shark through water. There are only context clues: a stark Manhattan office littered with elegant, minimalist movie posters; hushed phone calls about test screenings and trips to LA; and a young woman, with fear in her eyes, who arrives to pick up an earring left on the floor of the boss’s office. We know the predator in question is meant to be Harvey Weinstein.

The fact that Green allows him only to be referred to as “Him”, often in a timid whisper, speaks to the power of her film. “Him” might be Weinstein, but he could also be any of the other men – the ones not currently sitting in jail – who abuse their position in order to harm and exploit others. In preparation for the film, the director interviewed around 100 former and current assistants, working in different industries, compiling the results into a single character, Jane (Julia Garner). By following her daily toils, The Assistant captures the specific, nauseating feeling of both complicity and powerlessness – telegraphed so beautifully on Garner’s face.

8. Vitalina Varela

Portuguese director Pedro Costa’s cold, incurious worlds are a kind of collective hallucination. He traps his characters – drawn often from the dispossessed population of Lisbon – in shadows and in despair. In the last two decades, he’s also transformed himself into a canny combination of storyteller and documentarian. Vitalina Varela takes its name from its lead actor. It also draws from her life story. In the Eighties, Varela’s husband left their home in Cape Verde and fled to Portugal, promising that she could one day join him. In Costa’s film, she turns up three days after his funeral.

She’s left to waltz through Lisbon, her new purgatory, faced with a final and all-consuming sense of isolation. Her husband is gone, having left only a few traces of his existence. And the darkness never relents. The houses around her twist up like jagged bones, seeming as stiff and artificial as theatre backdrops. Costa’s tableaus are so potent, so emotionally haunting, that they’re almost impossible to shake, even after the film has ended and light has finally returned to the world.

7. Uncut Gems

For Adam Sandler, the artful and artless, Punch Drunk Love and Pixels merely represent two sides of the same coin. His characters are always some heady combination of bitter egotism, childish naivety, and impotent rage, making him the unappreciated master of ruffled masculinity. In the Safdie brothers’ Uncut Gems, he delivers the best performance of his career playing Howard Ratner, a gambling addict and jeweller in New York’s Diamond District. The actor toys with his audience’s empathy, disgust and pity like a cat with its next meal.

The bitter comedy of Uncut Gems is how easily Howard can be broken. It’s an almost punishingly chaotic film, though each jittery camera move and line of overlapping dialogue is carefully orchestrated. He’s humiliated time and time again – chewed out in public by his assistant (Lakeith Stanfield) and dressed down in private by his estranged wife (Idina Menzel). Even the person most loyal to him – his doll-faced, attentive lover (Julia Fox, in a knockout debut) – ends up screaming in his face outside a club at 3am. Howard may be pathetic, but both Sandler and the Safdies find ways to spin tragedy out of karmic retribution.

6. I’m Thinking of Ending Things

Writer-director Charlie Kaufman, once enough of an idealist to give his lovers in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind a second shot, has curdled in the intervening years. I’m Thinking of Ending Things is arguably his bleakest film – it’s also one of his best. “I’m thinking of ending things,” a young woman (Jessie Buckley) says to herself. She chews over the words, repeating them over and over again in the hope that they’ll suddenly gain the significance she was searching for.

She’s not quite sure what she wants to end. Is it her life? Her relationship with Jake (Jesse Plemons)? They’re on their first substantial trip together – a visit to his parents, out on their farm. But details start to change without warning: clothes, jobs and hobbies. Jake’s parents (Toni Collette and David Thewlis) age rapidly between scenes, as if we’re watching corpses decompose before our eyes. Kaufman has taken Ian Reid’s debut novel, published in 2016, and replaced its bait-and-switch ending with a single mood – one that’s not so much about suicidal ideation or break-ups as the black hole of emotions they have a tendency to create. Suddenly, I’m Thinking of Ending Things starts to feel like the most frightening film of the year.

5. Lovers Rock

Mangrove, the first entry in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe film anthology, may memorialise the political power of direct action, but the second, Lovers Rock, argues that the pursuit of personal freedom can be just as revolutionary. Set in west London in the early Eighties, the film sees director Steve McQueen’s camera wander through a “blues party” – Black Britons, not often welcome in white-owned music venues, would set up makeshift establishments in private homes, serving up good food and intoxicating slow jams.

Martha (Amarah-Jae St Aubyn, in a powerful debut) finds herself drawn to the gallant and charming Franklyn (Micheal Ward). McQueen lets the film luxuriate in their flirtations, while keeping audiences keenly aware of how men and women navigate public and private spaces. Power dynamics shift as the characters move between bedrooms, up and down the stairs, through the garden, and back into the living room, now an impromptu dance floor. It’s here that McQueen stages the year’s most memorable scene, as a crowd of dancers are entranced by Janet Kay’s 1979 track “Silly Games”. At first, the camera snakes through their hips, sexual tension dripping down the walls. Then the record ends, but the song continues, as a joyful chorus of voices continue its cry of uncorrupted freedom.

4. Portrait of a Lady on Fire

In Portrait of a Lady on Fire, director Celine Sciamma resists showing us the face of Heloise (Adele Haenel) for as long as possible. She’s the daughter of a countess (Valeria Golina) in 18th-century Brittany, sent home from the convent with an eye to securing a prosperous match. We first meet Heloise through the eyes of Marianne (Noemie Merlant), an artist invited to capture her likeness. The two of them are perfect opposites: Heloise’s gaze is piercing, the corners of her mouth turned down in a permanent scowl; Marianne’s eyes, meanwhile, are dark, wide, hungry.

With one look, we can already tell these women will fall for each other – even if they don’t yet know it themselves. Sciamma’s gorgeous, romantic film concerns itself almost entirely with the unseen power of the gaze. Through quiet, contemplative scenes, we’re invited to study these women just as they’re studying each other. But Portrait of a Lady on Fire isn’t only about the look between two women as lovers, but between two women in the position of artist and subject. As Heloise points out, when Marianne is painting her, where else is she meant to look but back at her?

3. Shirley

Josephine Decker’s film may be based on the life of Shirley Jackson, the great Gothic writer, but it isn’t tethered to it. This is a portrait not of her life, but of her genius. The filmmaker is free to imagine, however romantically, what kind of mind could have written the lonely, dark passages of The Lottery (1948) and The Haunting of Hill House (1959). The fictional Rose (Odessa Young) and her equally fictional husband Fred (Logan Lerman) are invited to stay a few days in Shirley (Elisabeth Moss) and her husband Stanley’s (Michael Stuhlbarg) ivy-covered home. A kinship grows between the two women.

It’s sexual. It’s spiritual. Their identities start to intertwine and blend into each other. Shirley is sensuous and beguiling, an act of pure witchcraft. The camera twirls like Stevie Nicks in one of her shawls; it stumbles towards the characters in order to scrutinise their faces. Moss, as excellent as ever, hardens her face into a predatorial glare. Her voice sounds both coarse and intimate, like she’s inviting you in on a terrible secret. When Rose confesses that Shirley’s writing makes her feel “thrillingly horrible”, you can sense an awakening on the horizon.

2. Jojo Rabbit

No one makes a comedy about a 10-year-old Nazi and his imaginary best friend, Adolf Hitler, and lives under the delusion that they’re in for an easy ride. Yet Taika Waititi’s film, which won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, manages to be tender, daring and sharp. It’s precisely pitched so that it keeps its path steady and its ambitions in check. The writer-director’s trademark goofy, freewheeling humour is deployed here as a form of humanisation – not to make the characters more sympathetic to audiences, but to illustrate how easily fascism feeds off banal human flaws.

Set in the last days of the Second World War, it follows Johannes “Jojo Rabbit” Betzler (Roman Griffin Davis), a young fanatic so desperate to be accepted, he’s conjured up a make-believe Führer (Waititi) to give him daily pep talks. Meanwhile, Rosie (Scarlett Johansson), Jojo’s secretly anti-Nazi mother, and Elsa (Thomasin McKenzie), the Jewish teen she’s helped hide away, tentatively share their visions of a better life, whispered to each other during their tête-à-têtes in the dead of night. The kind of hope Waititi’s film offers is fragile, but precious – that love might be enough to carve a path to the future.

1. Parasite

Back in February, when Parasite won Best Picture – the first film not in the English language to do so – it felt like anything was possible in 2020. Such optimism may have hideously backfired, but the joys of Bong Joon-ho’s razor-sharp, electrifying film remain. The director, whose work is as playful as it is sincere and revelatory, takes an impish joy in making audiences feel at home, then ripping the rug out from under them.

The Parks, including patriarch Dong-ik (Lee Sun-kyun) and his fluttery wife Yeon-gyo (Cho Yeo-jeong), are fortressed in a glass-walled, minimalist home. It’s into this shiny, hollow world that the Kim family try to integrate themselves, after the son Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik) is hired as an English-language tutor. He immediately hatches a plan to get the rest of the clan – his parents Ki-taek (veteran actor Song Kang-ho) and Chung-sook (Chang Hyae Jin), as well as his sister Ki-jung (Park So-dam) – employed. It’s exhilarating to watch their schemes, as intricately plotted as they are mildly preposterous, unfold. But the film, which marks Bong’s most daring examination of capitalism yet, has a few nasty surprises up its sleeve – everyone’s the “parasite”, and they all plan to leech off each other until they’ve been sucked dry.

The top 10 TV shows, as chosen by Ed Cumming

10. Devs (FX/BBC Two)

After Annihilation and Ex Machina, Alex Garland continued his journey into high-concept sci-fi with Devs, an ambitious, genuinely cinematic series about a mysterious computer mogul, Forest (Nick Offerman), who seems to have created a machine that can predict the future. Although its reach ultimately exceeded its grasp, Devs looked gorgeous, treated the viewer with unusual intellectual respect, and wasn’t afraid to take on the big philosophical questions emerging from Silicon Valley.

9. The Last Dance (Netflix)

Netflix and ESPN delivered a thrilling examination of one of the most irrepressible sports teams ever assembled, the all-conquering Chicago Bulls basketball side of the early 1990s. The Last Dance is several hours too long, and probably too forgiving of Michael Jordan, but the price of complicity with its star is unparalleled access, interviews with everyone still living who catered, and electrifying archive footage put together beautifully.

8. The Queen’s Gambit (Netflix)

From the outside, Netflix’s most popular new series was also its biggest challenge to date; a drama that made chess not only exciting but kind of sexy. It told the story of Beth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy), a beautiful red-headed orphan from Kentucky with addiction problems, who rises to the top in a male-dominated world, only needing the help of several men along the way. Critics noted the series’ masculine vision of female empowerment, but it was undeniably easy to watch, Taylor-Joy building a winning performance as she played out tense openings and cagey endgames in a series of opulent mid-century hotels.

7. Once Upon a Time in Iraq (BBC Two)

In an era of big-budget, glitzy blockbuster documentaries – see The Last Dance – this was a masterpiece of patient, devastating filmmaking, which used interviews with figures from both sides, and archive news footage, to tell the story of the Iraq war in five episodes. Beginning with the misplaced optimism before the US invasion in 2003, it took us through insurgency, the death of Saddam Hussein and through to the rise of Isis in the post-war political vacuum. If any doubts remained that the war was a tragic, stupid, destructive misadventure, they weren’t there by the end.

6. Quiz (ITV)

The playwright James Graham’s previous foray into TV, the Benedict Cumberbatch Brexit drama, caused much gnashing of teeth. This time he focused on a less contentious but hardly less fascinating episode in British history, the Who Wants to be a Millionaire coughing scandal. As well as presenting an unexpectedly two-sided view of a case that seemed to be open and shut, Quiz was a vision of a hopeful, early Noughties Britain that came as a lockdown tonic, with a typically sensitive performance by Matthew Macfadyen as the major.

5. Normal People (Hulu/BBC One)

Sally Rooney’s bestselling novel about Irish millennials in love was brought to the screen with unusual sensitivity, thanks to a script – by Rooney and the playwright Alice Birch – that gave the story room to breathe. Paul Mescal and Daisy Edgar-Jones had instant chemistry as Connell and Marianne, teenagers from opposite tax brackets who bond over a shared love of literature and contempt for their less industrious peers. Normal People provided dreamlike escapism at exactly the time BBC One needed it, although its abundant and prolonged sex scenes made it a more challenging watch for viewers locked down with their immediate family.

4. The Mandalorian (Disney+)

Although the flagship new Disney+ Star Wars launched in the rest of the world in 2019, Britain didn’t get The Mandalorian until March this year. It was abundantly worth the wait. A stylish western, with an impressive lead performance from the mostly masked Pedro Pascal, it proved Star Wars could ditch the lightsabers without losing the wit and warmth that made it loveable in the first place. All that before we even met Baby Yoda. For all Netflix and Amazon’s forays into original content, Disney+ is proving what can be achieved with a peerless back catalogue and shrewd handling of its IP.

3. Industry (HBO/BBC Two)

I'm friends with the writers, so I held off on Industry when it first came out. Now that everyone from The Daily Mail to The Guardian has five-starred it, I feel more confident I’m not being biased when I say this funny, filthy, fastidiously detailed look at graduates in finance was one of the best new dramas of 2020, with a cast of young, mainly British newcomers, a tight script and a tense, unforgiving vision of London. Or not just biased, anyway.

2. Dave (FX/BBC Two)

Smuggled out late at night on BBC Two earlier this year, Dave was an unexpected word-of-mouth winner, a sharp, zeitgeisty comedy based on the real-life adventures of David Burd, a white Jewish rapper from Pennsylvania who performs as Lil Dicky. Although his lyrics are often funny, he is not a novelty act, and entirely serious about his rap ambitions. Dave had soul to go with its laughs, especially in Dave’s relationship with his real-life hype man, GaTa, who played himself in one of the breakout debuts of the year.

1. I May Destroy You (HBO/BBC One)

Dark, smart, sharp and unexpected, Michaela Coel’s HBO/BBC drama-comedy was an auteur piece, the expression of a single creator’s vision. Written by and starring Coel, it was ostensibly about a writer in London putting her life back together after a rape. But it was much more than that: an exploration of youth, race, gender, sexuality and what it means to live and work in Britain in the 21st century, dished out in 12 half-hour episodes that refused easy answers without sacrificing wit or verve. In interviews for the series Coel revealed how hard she’d had to fight to get the creative control she wanted: not a problem she’ll have again, you imagine.

Read More

Moses Sumney: ‘Masculinity isn’t necessarily negative’

Douglas Stuart: ‘Homophobia makes you think there’s something broken’

Why Kitty Green’s Weinstein-inspired ‘The Assistant’ needs to be seen

Céline Sciamma: ‘Ninety per cent of what we look at is the male gaze’

Normal People’s Paul Mescal on mental health, sex scenes and love