Brian May: ‘I don’t find it easy living in this world today’

Under fluorescent strip lights in the archive library at King’s College on London’s Strand, Brian May is transporting me back in time. On the table between myself and the Queen guitarist is an original Victorian stereoscope, a box-like wooden contraption that is akin to a primitive pair of virtual reality goggles. “Take a look,” he says.

Although May is best-known for playing arenas with the band he formed over 50 years ago, one of his numerous scientific hinterlands away from the stage is stereoscopy. For the uninitiated, it was an early way of looking at photographs via a special viewer that fused together two flat images to create a single 3D picture. Stereoscope machines entranced Victorian society for a short period in the 1850s and 1860s before being usurped by a different craze.

But Queen Victoria was an avid fan. Charles Dickens too. And May, who has a PhD in astrophysics and has collaborated with NASA, owns one of the world’s biggest collections of stereo photo cards (150,000 images and counting). He has also revived the long-defunct London Stereoscopic Company, which publishes books on the phenomenon including the new Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D.

May’s glee is clear when I’m taken aback at the sheer 3D-ness of a picture of the 1851 Great Exhibition. Later, he’ll pick up his smartphone, take two pictures of me, and turn me into a stereoscope photo card. “Every time somebody goes ‘Oooh, really?’, somebody who hasn’t experienced it before, it’s just a joy,” the 74 year-old says. We all take the notion of 3D for granted. But you can trace all use of the medium – from the films Avatar and Jaws 3D (my first encounter with it) to ABBA’s upcoming tour as dancing CGI ‘ABBAtars’ – back to this Heath Robinson-esque Victorian box.

As we chat, it emerges that these strange contraptions have modern resonance in another way too. They fired the starting gun on society’s obsession with seeing pictures of celebrities. Far from being an esoteric curio from almost two centuries ago, stereoscopes were a forerunner to Instagram. May’s obsession, far from being a flash in the pan fad, was actually very prescient.

Still, our encounter in a hushed library feels slightly incongruous. I’m used to seeing May under different lights, playing to a different audience. Indeed, the musician should have spent much of lockdown touring the world. Next summer Queen and Adam Lambert, the singer who replaced the late Freddie Mercury who died 30 years ago this month, will play 10 nights at the O2 in Greenwich. But here, in the hushed academia of King’s, May’s trademark periwig-like silver curls are the only reminder of that other job. Today, we’re here to talk about the unsung Victorian hero who invented the stereoscope in 1832, a man called Charles Wheatstone.

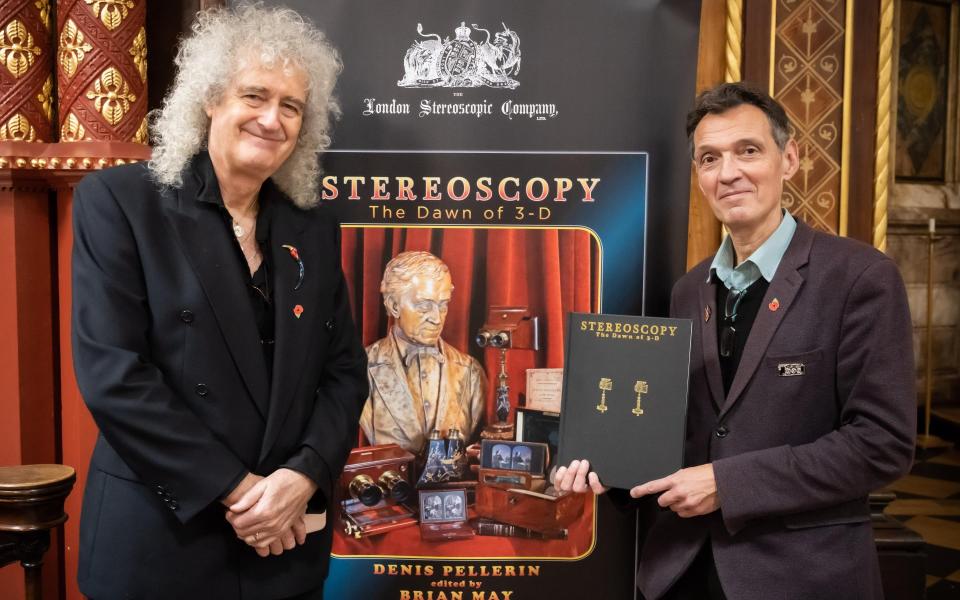

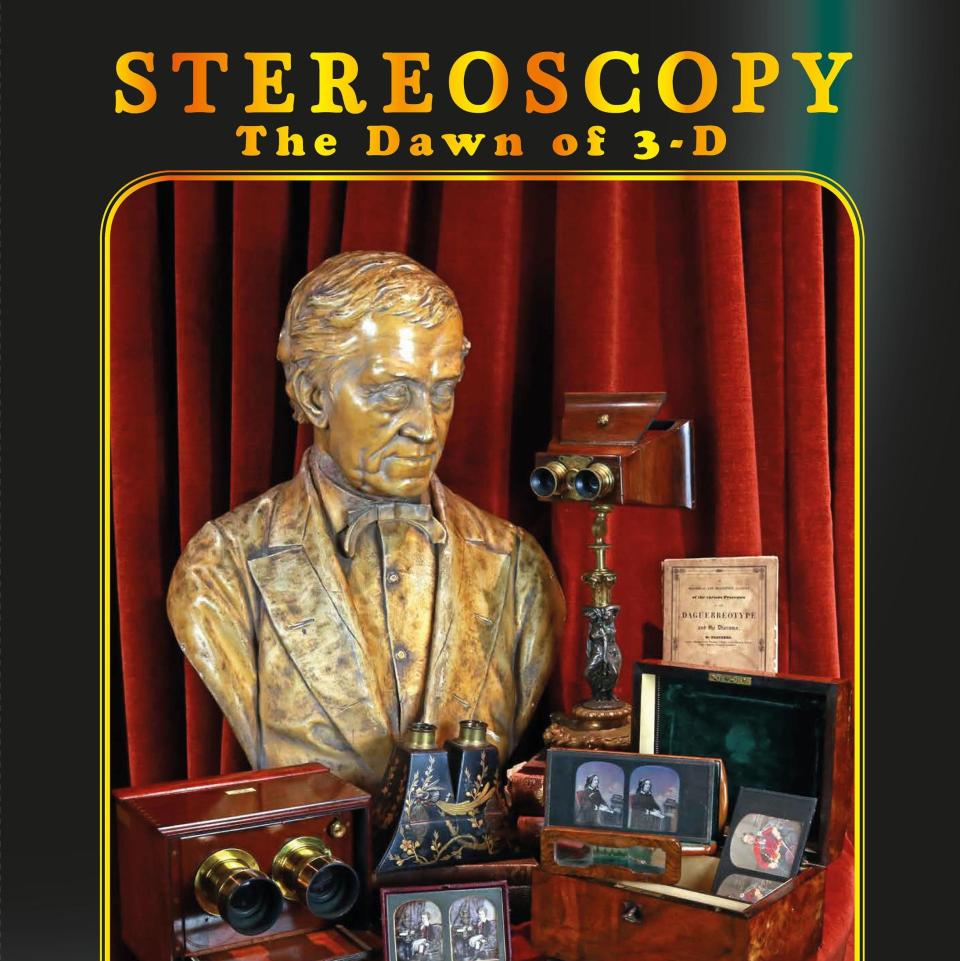

May and his co-author Denis Pellerin, a French academic who joins us for the interview, believe Wheatstone should be as well-known as more famous Victorian-era inventors such as Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell. It’s one of the reasons they wrote Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D – to try to raise Wheatstone’s profile.

Wheatstone was one of those all-round Victorian inventors and academics, for whom the distinction between art and science didn’t exist. Interesting things were just interesting things. So as well as being Professor of Experimental Philosophy at King’s, which is now the home of his archive, he invented the concertina (and another musical instrument called the symphonium). Those Victorians knew how to multitask. Wheatstone first demonstrated the stereoscope in 1838 after he realised that humans’ perception of depth is mainly due to a thing called stereopsis, when our brain takes the different images from our left and right eyes and combines them into one 3D image. His machine simply replicates this process. May and Pellerin point out that stereoscopy actually predates photography, a term that wasn’t even coined until 1839. “He was a true polymath,” says May. “Wheatstone was a true genius and, yes, should have his place on that pantheon [with Edison and Bell].”

The stereoscopy craze took off in the years following the Great Exhibition. The golden era was between 1856 and 1862 when mass production saw the price of photo cards falling, meaning that middle-class families could buy into stereoscopy. For a nation used to seeing pictures in magazines and newspapers made from woodcut blocks, this was revolutionary. “Christmas 1857. That was really when the craze started, especially with the ghost in the stereoscope. Manufacturers couldn’t produce enough, such was the demand. They had to apologise in the press,” says Pellerin.

The “ghost in the stereoscope” refers to a craze within the craze for phantoms to appear in photos. They were a sort of spooky novelty. Global landmarks, such as the pyramids at Giza, were also popular. “You are in Egypt, you are in China, you are in Japan. By 1859 you could see the whole world in 3D,” says Pellerin. But it was pictures of famous people that the public really wanted to see.

Pellerin and May’s book – which comes with a collapsible, May-designed stereoscope called The Owl – is full of stereo pictures of celebrities of the day, from the reigning monarch to Isambard Kingdom Brunel to Dickens (a catalogue for the London Stereoscopic Company was included in the tenth instalment of Little Dorrit). In 1857 the diminutive American performer Charles Sherwood Stratton – better known as General Tom Thumb – came to London and had more than a dozen stereo cards made of himself. They included photos of him posing with members of the Household Cavalry (Stratton travelled over with his distant relative and manager P. T. Barnum, the original greatest showman). The public lapped up the pictures.

“You have to remember that Victorians are very much like us. They love celebrities and they love to be able to see them,” says May. “And, of course, before this was invented they couldn’t really get close to them. The newspapers wouldn’t have proper photographs in them and they certainly weren’t 3D. So suddenly it’s like they’re in the room with their favourite politician or actor.”

So stereoscopes were, in a very literal sense, the first form of social media. The cards gave people a glimpse into the world of the rich, the famous and the hitherto unattainable. Viewing or owning cards made people feel close to fame by proximity. But in the early 1860s the form was usurped by a different fad called cartes-de-visit. Cartes-de-visite were playing card-sized 2D photos that people collected, swapped and kept in albums, rather like football cards. They’d intersperse pictures of themselves and friends with pictures of celebrities, also to give the impression of closeness to fame. While arguably less exciting than stereo cards, cartes were simpler to view, which may explain why they took off. Again, there are modern parallels: one platform replaces another. Facebook one decade, TikTok the next.

Still, stereoscopy is fascinating. May got hooked as a child when a stereo card of a hippopotamus fell out of a Weetabix box. “Suddenly the hippopotamus was real. I could smell its breath, I could fall into its mouth,” he recalls. Pellerin fell for stereos when he saw a picture of the Tuileries Palace in Paris. “For 10 seconds I was there,” he says. May says that the fad of 3D still falls in and out of fashion. “It’s very odd how stereoscopy becomes huge, then disappears, then becomes huge again,” he says. There was, for example, a revival in 1900 and then it disappeared again. “Even with the Avatar film. Suddenly stereoscopy was everywhere. Everyone was making films in 3D, and all TVs were ‘3D-ready’ only a couple of years ago. Try and find one now! It happens every time.”

Mercury knew all about May’s fascination with stereoscopy. The guitarist would take a stereo camera on the road (there is even a stereo book of Queen photos). “Oh yeah, Freddie saw me with my stereo camera. In fact, in the Queen book there is a stereoscopic picture of him taking a picture of me with his Polaroid. That was his passion. Taking Polaroids and instantly having pictures that he could share with his friends.”

As we’ve been talking about social media, I ask May what he thinks Mercury would have made of the modern world. Because with the openness and instant gratification of social media also comes cancel culture. The upside and the downside. They are, in a way, two sides of the same coin.

“I don’t find it easy living in this world today. I think Freddie would have been the same,” says May. “Freddie was very outspoken and, in common with [astronomer] Patrick Moore who was a very good friend of mine from a previous generation, the kind of way that people spoke in those days is not allowed these days.” While May sees tremendous good in encouraging people to be respectful, he doesn’t think gagging people is the way forward. “I don’t fit in very well and I don’t think Freddie would have fitted. Patrick Moore wouldn’t have lasted five minutes,” he says.

That May is occasionally ill-at-ease with the modern world became clear earlier this week (after our interview), when he criticised the Brit Awards for making its categories gender neutral in a bid to become more inclusive. May told The Sun he thought the Brits' decision was "ill-thought-out" and claimed it was a "knee-jerk reaction" to cancel culture. “I feel very uncomfortable about some of the decisions that are being made, often out of fear. Because people are so afraid of being called out. It is a horrible atmosphere,” he is reported to have said. "I worry about cancel culture. I think some of it is good but it also brings bad things and injustices. We think in different ways but they weren't necessarily worse ways.”

He told The Sun, “For instance, Freddie wasn't white but nobody cared. He was a musician. He was our friend, our brother. We didn't have to stop and think, ‘Oh should we work with him? Is he the right colour or the right sex?’ It's frightening that people have to be so calculated about things. To me it is dangerous.”

Bearing all this in mind, it is perhaps fitting that the guitarist's hinterland lies away from the minefield of identity politics and cancel culture. Stereoscopy harks back to different, some might say simpler, times. Perhaps, as Pellerin wryly jokes at the end of our chat, living in the nineteenth century is easier after all.

Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3-D by Denis Pellerin and edited by Brian May is published by The London Stereoscopic Company (www.londonstereo.com)