Drugs, mobsters and bungling goons: the strange kidnap of Frank Sinatra Jr

The hare-brained, bungled abduction of 19-year-old Frank Sinatra Jr – son of the great singer Frank, and younger brother of Nancy – was one of the most infamous kidnappings in American history. The full tale of this extraordinary crime is the subject of a new 10-part podcast called The Grand Scheme: Snatching Sinatra, in which narrator John Stamos, star of the Disney+ sports comedy Big Shot, talks to the last surviving kidnapper, 81-year-old Barry Worthington Keenan. As Stamos puts it: “This wacky story is like the Marx Brothers meets the Coen Brothers.”

Keenan, who was born in Los Angeles on June 26 1940, had a traumatic upbringing in Malibu. His father was an alcoholic stockbroker; his strict Catholic mother was often depressed and sometimes suicidal. As a child, Keenan began hearing voices, including from a group of angels he dubbed “The Committee”. He was also self-harming. In past interviews, Keenan has jokingly referred to himself as “Crazy Barry” and admitted “sane people don’t do what I did”.

After leaving University High School in Los Angeles – where Nancy Sinatra was a fellow classmate – Keenan became a successful businessman. At 21, as the youngest member of the LA Stock Exchange, he was making around $10,000 a month. In 1961, everything went sour for Keenan, however, after he was involved in a car accident that left him with a damaged back. He quickly became addicted to the painkiller Percodan, and began drinking heavily. All this coincided with a real-estate collapse that wrecked his share portfolio and his father’s business. Keenan was reduced to selling transparent window shades to stores in the Mojave desert. “I was an unemployable drug addict who couldn’t think straight,” he said in 2013.

Depressed and high on amphetamines, he was relaxing on Newport Beach’s Balboa Island when, he said, God spoke to him through a small transistor radio. “The radio was off at the time,” he added, deadpan. He claimed that the Lord informed him that crime was the solution to his problems. “God was talking to me and we discussed robbing a bank or a grocery store,” said Keenan. He said God finally suggested kidnapping someone, making it clear that he was ruling out either a baby or a woman. Looking back in 2002, Keenan told broadcaster Ira Glass that he realised he was in a “demented state” when he suddenly decided that “kidnapping seemed like a good idea”.

Keenan spent several weeks at Palm Springs Public library researching kidnappings, in search of an “air-tight plan” for “the one big hit that would cure everything”. Among the books he pored over was Persons in Hiding, written in 1939 by FBI director J Edgar Hoover. Keenan made a long list of possible victims, including Bob Hope’s son Tony, one of Bing Crosby’s sons, Robert Mitchum’s son Jim and Johnny Weissmuller Jr. He suddenly remembered old schoolmate Nancy and thought of her brother, Francis Wayne Sinatra.

“I put a five-year business plan together,” Keenan told Glass, “and I typed it up and put it in a binder.” He was careful to call it “the plan of operation”, rather than kidnapping. He was adamant that no one was going to get hurt in the crime, and that he would pay back the $240,000 ransom once he’d used it to fund investments that would make him rich. The business plan even included a section called “Benefits to the Sinatra Family”. Keenan thought the kidnapping would bring Sinatra closer to his son and change the singer’s image from a man who hung out with gangsters to a sympathetic one of the “worried parent”.

All in all, it was, as Stamos puts it bluntly, “a terrible f---ing plan”.

At this point, in September 1963, Keenan brought two inept co-conspirators into the equation: his lifelong friend Joseph Clyde Amsler and his mother’s ex-boyfriend John William Irwin. It’s safe to say that neither were criminal masterminds. Keenan trusted 23-year-old unemployed shellfish diver Amsler – their only previous criminal experience was lighting palm trees on fire for laughs – and thought that 42-year-old house painter Irwin had the type of “gruff voice” that would be convincing on the ransom call to Sinatra. Both accepted the offer of a $100-a-week retainer as “assistants”, although neither really believed that “the plan of operation” would actually happen.

In October 1963, Keenan travelled to Phoenix, Arizona, and bought a small pistol for $55 from a gun collector called Howard M. Robinson. He wanted to use it to scare Frank Jr into compliance when he was snatched before a concert with the Tommy Dorsey band at the Arizona State Fair on November 1. They got spooked and abandoned the attempt at the last minute. Keenan decided to try again on November 22, having come up with a new plan to seize Frank Jr from the Ambassador Hotel in LA. Keenan later told reporter Peter Gilstrap that when he rang the hotel to gather useful intel, the switchboard operator suddenly started sobbing, telling him that President John F Kennedy had been assassinated. The second attempt was postponed.

It was third time lucky for Keenan and his gang. At 9pm on Sunday 8 December, Frank Jr, already a singer himself, was playing the sixth night of a three-week stint at Harrah’s Hotel and Casino in Lake Tahoe, Nevada. Wearing ski jackets and posing as delivery boys, Keenan and Amsler entered room 417 at Harrah’s South Lodge, carrying a box filled with pine cones. Sinatra and his friend, 24-year-old trumpet player John Foss, had just finished dinner and were listening to tape recordings. Keenan, wearing a fake moustache, put down the box, took off a black glove and produced the small pistol. Sinatra Jr later testified that they threatened to shoot if they were given “any trouble”. “I decided to co-operate,” he added, “because my friend’s life was in jeopardy, as well as mine.”

They forced Foss to lie on the floor and taped his hands and eyes. “I could see ‘Junior’ looking at the bullets,” Keenan said in 1997. Frank Jr was given two sleeping pills and had a blindfold put over his eyes. The singer was led down the corridor, with a gun jammed into his ribs, and forced into the back of a 1963 Chevrolet Impala convertible.

It was at this point that the slapstick elements of the crime began to ramp up. Just as they were about to set off on the 430-mile drive to the “safe”-house on Mason Avenue in LA’s San Fernando district, Keenan, who was sleep-deprived and on drugs, realised he had left his gun (and moustache) on the bed. He went back to the room to retrieve them. He then realised on the way that he had forgotten the cash for petrol. He took a $20 bill from Sinatra Jr’s wallet to pay for fuel on the way back to California.

The pair, alas, had failed to tie Foss securely: he quickly freed himself and alerted the authorities. Within an hour the FBI office in Reno had spoken to Sinatra, who was filming Robin and the 7 Hoods in Burbank, California at the time. According to the book Crimes of the Centuries, the man-hunt comprised 100 local and state law enforcement officials, along with 24 FBI agents. By 10pm, roadblocks had been set up along the major roads out of Reno, including those through the Sierra Nevada mountains. “It was very surreal knowing that I was the most wanted man in the country,” Keenan said.

In 2013, Keenan told the BBC World Service Witness Archive that when he realised there was a roadblock ahead, he reasoned that the FBI were looking for three men. He ordered Amsler to get out of the car and slip through the mountain terrain and find them on the other side of the roadblock. He made Frank Jr gulp down some whiskey, explaining to the officers that the reason his passenger was stretched out on the backseat was that they had been to a party and he’d had too much to drink. The ploy worked and got them through the barricade.

By this time, a blizzard was blowing, and when they pulled up out of sight of the officers, Amsler was nowhere to be seen. When he finally appeared, he was covered in blood. “Unbeknownst to me,” Keenan recalled, “Joe had run into the branch of a tree and knocked himself out. He had a huge gash in his face.” Keenan put the injured Amsler into the trunk of the car and resumed the drive to Mason Avenue.

With no news of his son, Sinatra was frantic as he waited for a ransom note. The singer’s publicist Jim Mahoney later described him as “a nervous wreck”. The US Attorney General Robert Kennedy and J Edgar Hoover offered the government’s support, and even mafia boss Sam Giancana volunteered his services. “Please let the FBI handle this,” Sinatra reportedly told the mobster. Irwin finally made contact a day after the kidnap.

The next instalment in the comedy of errors came with Irwin’s instruction to Sinatra and the FBI to head for a gas station pay-phone in Carson City to hear details of the demand. The inept gang did not give Sinatra enough time to get there. Irwin made four telephone calls to the gas station, asking to speak to Frank Sinatra. By the last call, the mechanic was so fed up of what he believed to be obvious prank calls that he blew a fuse. “He uttered a few four-letter words” and slammed down the receiver, recalled Keenan. Stop to picture the poor mechanic’s face when, minutes later, a posse of FBI cars pulled up and one of the most famous faces in the world stepped out to plead, “My name is Frank Sinatra, have I had any calls?”

Fortunately, Irwin tried again. After being allowed to speak to his son for 30 seconds, Sinatra offered them a million dollars for the safe return of Frank Jr. To his surprise, Irwin turned down the million and insisted they wanted only $240,000 ($1.3million in today’s money), giving the location for the delivery. “Frank seemed puzzled but wrote down the denominations we demanded,” Keenan told the BBC.

In the early hours of December 11, Sinatra and an FBI agent duly placed an attaché case containing $239,985 beside a school bus at a gas station on Sunset Boulevard. It was picked up by Keenan and Amsler, both of whom were caught on film by the authorities. Although they evaded capture, by the time the pair got back to Mason Avenue, Irwin had already freed Sinatra’s son, dropping him by the Mulholland Drive overpass. Frank Jr walked to the nearby Bel Air enclave, and a security guard drove him to his mother Nancy Barbato Sinatra’s home, putting him in the trunk to fool the media pack waiting outside.

When news of his safe return broke, both father and son made brief statements to the press. “We are just thrilled here at the house that he’s back and nobody was hurt,” said Sinatra, while Frank Jr. told reporters: “Fellers, the only thing I can say at this time is that as soon as I returned home last night I was so exhausted that almost immediately I went to sleep, and I haven’t had the chance to talk to the authorities yet.”

That sleep gave the three criminals a day to enjoy their money. Theresa Gray, who rented them the apartment in Canoga Park, said she saw them spread the money out on the floor and begin dancing around it. “They were throwing it at each other, they were playing football with it.” Gray later testified. They went out on a quick spending spree. Keenan dolled out $6,000 on a new car and furniture for his ex-wife, while Amsler bought a motorcycle.

But the FBI net quickly closed, and Irwin was the first to break. On December 13, after spending the night at his brother’s home in Imperial Beach, he confessed that he was “sick of participating” in the kidnapping and wanted to turn himself in. His brother called the FBI office in San Diego and they arrested Irwin with a bag containing $47,938 of the ransom money. Irwin gave the FBI a 27-page confession. Amsler and Keenan were also quickly arrested.

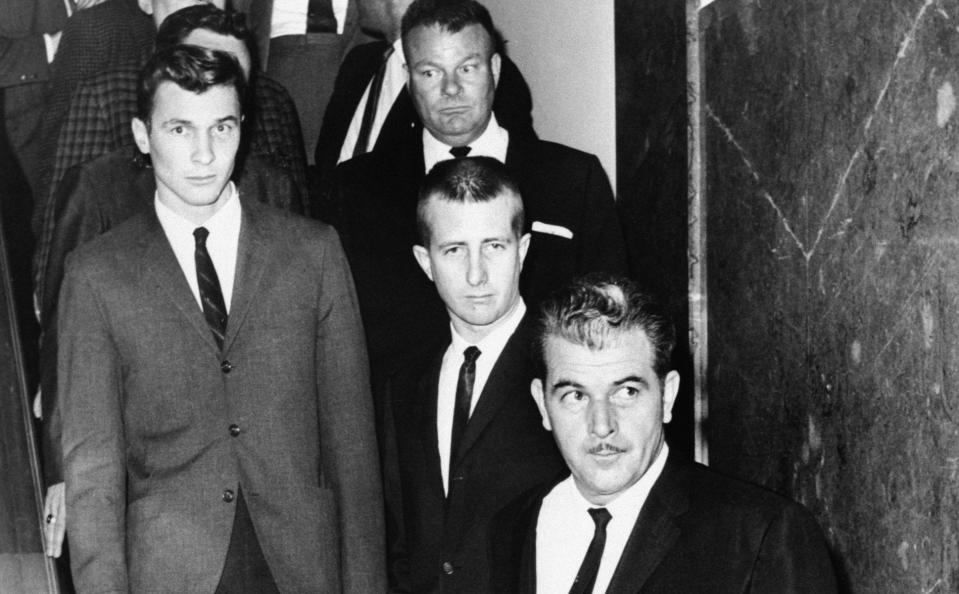

The federal trial of the three men started on February 10, 1964, with all three pleading not guilty to a six‐count indictment arising out of alleged kidnapping and interstate transportation. The reason they pleaded not guilty was that their defence team were now claiming that Frank Jr, or possibly his father, had orchestrated the kidnapping as a publicity stunt to promote the teenager’s career. When this false claim was later repeated by some British news organisations, it ended with them having to pay libel damages to the Sinatras. “This family needs publicity like it needs peritonitis,” Sinatra said.

The trio’s main lawyer was an outrageous publicity-seeker called Gladys Towles Root, who was known to turn up in court wearing giant hats, fur coats, outsize costume jewellery and skirts with massive taffeta trains. She and fellow trial lawyer George A Forde were later charged with “unlawfully, willingly and knowingly” inducing Amsler and Irwin to testify falsely that Frank Jr. had permitted himself to be kidnapped as a publicity stunt. (Root was cleared in 1968.)

Her shenanigans failed. The jury of nine men and three women did not believe that Frank Jr was involved in “chicanery”, or that he had dodged numerous chances to escape, or that he had a “a planned, contractual agreement” with his own kidnappers in an attempt to further his career. They returned guilty verdicts. As the “mastermind” behind the plot, Keenan was ordered to spend 75 years in prison, while Amsler and Irwin were both sentenced to 16 years and eight months.

The claims that the kidnap had been a hoax remained a nightmare for the Sinatra family. “The criminals invented a story that the whole thing was phony,” Frank Jr said in 2012. “That was the stigma put on me.” Keenan later admitted that the claims were “unfair and a blatant lie”.

As it happens, all three kidnappers were out before the end of the 1960s. Both Amsler and Irwin were released after three and a half years and Keenan was paroled in 1968, after serving less than five years, having been declared “insane” at the time of the crime.

In the immediate aftermath of the trial, Sinatra was livid about a letter from Father Roger Schmit, a Catholic Chaplain who worked for the Bureau of Prisons, asking him to forgive Keenan and Amsler. In a long reply, on 27 July, the singer said he was still angry over the claim of a hoax by his son, and “distressed and disturbed” by Schmit’s intervention. “The conduct of the defendants during the trial and afterwards has caused the Sinatra family great anguish and suffering… suspicion was created in the minds of many people as to the honesty and truthfulness of our son.”

Sinatra was not a person to have as an enemy. His own past was violent and vengeful. During an argument with jazz star Buddy Rich, he’d thrown a pitcher of water at the drummer’s head, narrowly missing. Sinatra had also thrown a champagne bottle at the head of his then-wife Ava Gardner and the singer only headed off a charge of assault and battery brought by journalist Lee Mortimer by offering a substantial private payment.

Jackie Mason, who was 93 when he died on 24 July this year, paid a particular price for making jokes about the 50-year-old singer’s marriage to 21-year-old actress Mia Farrow. (“Frank soaks his dentures and Mia brushes her braces,” the comedian told audiences.) An unidentified gunman fired three shots from a .22 pistol into Mason’s Las Vegas hotel room. Mason continued making jokes about Sinatra’s marriage, after which he was attacked by two thugs wearing brass knuckles, shattering his nose and jaw. And yet Mason, his jaw wired back together, continued to be brave (or reckless) enough to keep the singer in his routine, joking: “Frank Sinatra saved my life one night. He said: ‘Boys, that’s enough.’”

Stamos revealed that he was first told about Keenan’s part in the crime in the late 1960s, when his friend Dean Torrence, of the surf-rock duo Jan and Dean, said he had a manuscript Keenan wrote while he was in Lompoc Jail in Santa Barbara. Stamos told People magazine that he took the document and “just threw it in a box”. Stamos has said that part of the reason the full story of the kidnap took so long to come to light was that “Frank didn’t want the story told… it was an embarrassment” – meaning, presumably, that feared the consequences of being the man to tell it.

More than half a century later, Stamos met Keenan over lunch and decided to tell his story in detail, with the use of copious interviews. One of the most remarkable claims from the podcasts is that Sinatra tried to have Keenan killed even after the trial. “There were three attempts on my life by inmates who thought they might get in good with Sinatra,” Keenan alleged. Stamos says that he believes Sinatra “put a number of hits out” on the convicted kidnapper.

One memorable attempted murder, at Huntington Beach in Orange County, ended (aptly) in more farce. In a Zoom interview with Stamos, Keenan recalled: “The guy who was shooting at me on the beach had me dead-to-rights in his scope. His colostomy bag broke and caused him to miss me. He fired off a couple more shots, the sand popping up in front of me, so I just ran.” Stamos told ABC’s Good Morning America show that Keenan was saved by running to the lifeguard stand, which must have prompted the would-be assassin to gather up his colostomy bag and flee.

Frank Jr would always remain sensitive about the kidnapping. When Keenan sold the film rights for Snatching Sinatra to Columbia Pictures in 1999 (shortly after Sinatra Sr died at the age of 82), Frank Jr obtained a restraining order to prevent Keenan from receiving any payment. Although Leonardo DiCaprio was reportedly interested in playing Keenan, the film never got off the ground.

In April 2004, Showtime screened their own movie about the escapade, called Stealing Sinatra, which starred David Arquette as Keenan and a hangdog William H. Macy as Irwin. It was based solely on trial transcripts, and Keenan received no money for the film. By then, he had reinvented himself as a successful real-estate developer in Texas. After some more trouble in the 1970s – when he was taking a lot of LSD and was arrested for a drink-driving offence – he turned his life around and was moving in influential circles again.

In 1980, he married Sasha White, a close friend of Laura Bush. “I didn’t know he kidnapped Frank Sinatra Jr,” White later admitted. “I just thought he was this handsome, charismatic go-getter.” Keenan and his wife would often visit George W Bush and Laura Bush in the early 1980s. “If George and Laura ever knew about my past, they didn’t bring it up,” Keenan said.

Despite divorcing White in 1984, Keenan continued to make his fortune, including in the field of casinos and gaming. He also said that he had long ago stopped hearing the voice of God, adding “that went away when I sobered up and got psychiatric help”. Frank Jr’s fortunes also improved with age. A year after the trial, his debut album, a collection of standards called Young Love for Sale, flopped, in a year in which Beatlemania was at its height in America. But he continued singing for the rest of his career and had dozens of appearances in films and television shows, including providing his own voice for two episodes of Family Guy.

Little is known of what happened to Irwin after his release from prison. He reportedly died “in the 1990s”. But Amsler’s postscript was more intriguing. After his release from prison, he worked as a stunt double and bodyguard for Ryan O’Neal, in such movies as The Thief Who Came to Dinner and What’s Up, Doc? He later worked in construction, before moving to Roanoke, Virginia, where he was known as a “kindly old man who doted on his dog Sparky”. His son Chris Amsler, who was born while he was in prison, became a musician. The former kidnapper died of liver disease in May 2006, aged 65.

Keenan told local newspaper The Roanoke Times that Amsler always “felt very guilt-ridden” about being involved in what he called “our big mistake”. The 6’2” former navy man was, he added, “deeply upset” by being portrayed as violent in the Showtime film, having prided himself on looking after Frank Jr during his 54 hours in captivity.

Stamos calls the kidnapping of Frank Sinatra Jr “a wild story”, and it’s certainly one full of oddities. Nothing strikes me as more bizarre, however, than the way Keenan’s path continued to cross with Frank Jr in the years before the singer’s 2016 death. Keenan first tried to make contact with his victim from Lompoc Jail. “I wrote him a four-page letter and asked for a ‘face-to-face’ opportunity to make amends,” Keenan said. “He didn’t want anything to do with us, and I can’t say that I blame him.”

Yet they mixed in the same social circles. They came across each other at cocktail parties in Los Angeles, & even chatted backstage after a Frank Jr concert in Malibu in 1994. “I didn’t think it would be appropriate to tell him who I was,” Keenan said in 2000.

“I’m pretty sure he didn’t want to be reminded of that time in his life – and I didn’t want to be reminded either.”

The Grand Scheme: Snatching Sinatra is available on audio platforms, with new episodes released each Tuesday