Exit Stage Left by Nick Duerden – what happens once the hits have dried up?

These profiles of ageing rockers ponder whether it’s better to burn out, fade away or buy a house in London, writes the former frontman of the Ordinary Boys

I remember opening for the Who towards the end of my time in the Ordinary Boys, the band with whom I enjoyed brief fame in the 00s. Roger Daltrey, then in his late 60s, sang, apparently without irony: “I hope I die before I get old.” It made me think: “What’s next? Maybe I could find a nice job in advertising.” It’s a question that almost every performer faces in an industry that fetishises youth: is it better to burn out or just fade away? And then what? Where do you go? What do you do? How do you move on?

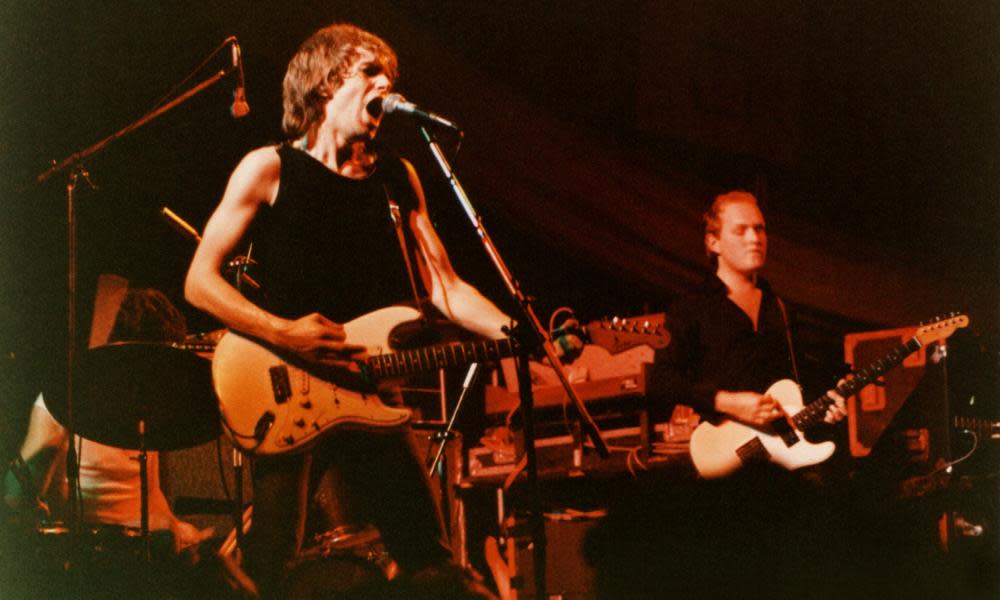

These are the questions Nick Duerden poses in his new book, Exit Stage Left. Each chapter serves as a condensed musical biography. The opener is a sensitive account of the life and career of Peter Perrett of the Only Ones, whose 1978 release Another Girl, Another Planet is one of punk’s great pop songs. But “artists really aren’t the best people to operate the heavy machinery of adulthood” and a regrettable incident in a car park in California while supporting the Who (them again) had them thrown off the tour and sent back to England, where he spent the next couple of decades struggling with substance dependency. There’s a redemptive arc in Perrett’s story and it’s incredibly moving to read.

If there is one takeaway for how to survive a career in pop music it seems to be 'buy a house in London in the early 80s'

Blistering first acts share the same energy: the big break, the world tours. But here are fading encores, empty assembly rooms, silence. As Tony James asked himself after Sigue Sigue Sputnik failed to deliver on their second album: “Do I crawl away and die now? Or do I do something else?”

The book isn’t all punk and indie stars, or redemptive arcs for that matter. What of those pop artists who reached their successes within parameters chosen for them by the Simon Cowells of this world? There is the story of pop R&B band Damage, whose skin colour saw songs intended for them being handed to the likes of Westlife and Boyzone, who the industry decided were more marketable. One of the hardest sections to read is the tragicomic tale of Paul Cattermole from S Club 7. This time, Duerden skips the origin story and we hard-cut to washed-up Cattermole being prodded by the Loose Women on daytime television where “a ticker-tape banner at the bottom of the screen reads ‘I’m Broke’”.

Most of the stories are cautionary tales. If there is one takeaway for how to survive a career in pop music it seems to be “buy a house in London in the early 80s”. Or perhaps try not to do too many drugs.

Spending my formative years in the dizzying plastic reality of my own stint of pop stardom left me wholly ill-equipped to navigate the real world afterwards. Being micromanaged for so long by agents who then disappeared overnight was a lonely experience. I made a conscious decision to end my celebrity career when I suspected that decision was not far from being made for me. This didn’t make the change any less jarring. I told my bandmates that I was quitting the band, packed a bag and bought a one-way plane ticket to Philadelphia. I remember walking past a magazine rack lined with front-page stories about my divorce as I boarded. I stayed away for three years.

But if a career in pop music is so often about managed decline, what is wrong with gracefully managing that decline? Why is a band touring in smaller venues than they had previously played or selling fewer records than they did in their early 20s met with such ridicule and contempt? Allan “Boff” Whalley from Chumbawamba, who retired from the band aged 51, puts it like this: “The bands I loved, when they split up, I always thought it was a beautiful thing. And those bands that I loved who then got back together – well, it never felt right.”

One fact emerges clearly from every story in Exit Stage Left: there is an unshakable identity that crystallises in anyone who has had any pop success. No matter what I do with my life I will always be Preston from the Ordinary Boys. It is that burnt-on identity that is at the heart of this book. It’s the “from” that follows the name of every interviewee. I now split my time between LA and London writing songs for other artists. I have a house in London and a trickle of royalties. I do have occasional pangs of regret. And I’m certain I will at some point ill-advisedly self-fund another Ordinary Boys record that no one will hear.

• Exit Stage Left: The Curious Afterlife of Pop Stars by Nick Duerden is published by Headline (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply