‘He'd write the waiters poems’: Peter Cushing, remembered by the people of Whitstable

Among the more seasoned of Whitstable locals, interactions with the late British actor Peter Cushing (who bought a quaint seaview house in the area back in 1958) are treasured like a letter from the Queen. My callout posts for memories of Cushing – who died 27 years ago this month – on two Facebook groups dedicated to local residents quickly generated hundreds of passionate replies, many treating their experiences with the shock and awe of a Bigfoot sighting. Some tell me he’d find the gentrification of modern Whitstable “obscene”; others claim they’ve seen his ghost inquisitively wandering around the harbour in the moonlight.

“Peter would always doff his cap to you and make you feel special,” says Steve Keeler, a trustee at the Whitstable Museum with vivid memories of Cushing. A child-like wonder begins to fill the 66-year-old’s eyes while reflecting on the underrated actor, who memorably portrayed Doctor Who and Sherlock Holmes, as well as starring in iconic productions of everything from Nineteen Eighty-Four to Dracula and The Mummy. “If you were lucky to be in his orbit, even for a few seconds, it left a real mark on you.”

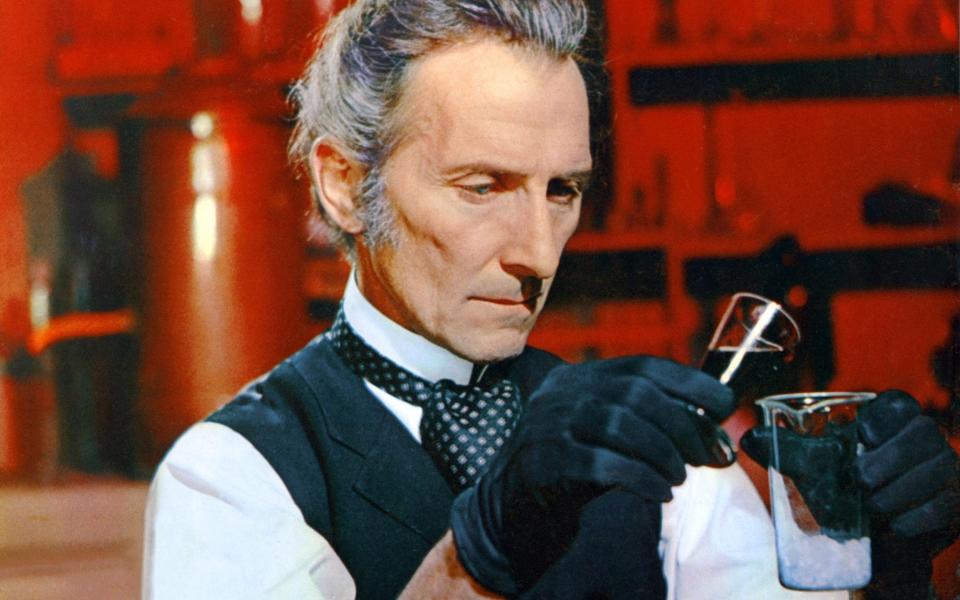

This admiration was clearly shared by Cushing’s Hammer Horror co-star Christopher Lee. He lovingly referred to his celluloid soul mate as a “great perfectionist. Peter learned not only his own lines but everybody else’s lines as well. He was the most gentle and generous of men.” George Lucas, meanwhile, was such a fan of Cushing’s acting ability that he entrusted him with the role of the Grim Reaper-like Grand Moff Tarkin, the personification of emperor imperialism in 1977’s Star Wars. Although Cushing never ascended to Hollywood royalty, the way he delivered witty lines like “You can’t mesmerise me, I’m British” in 1976’s At The Earth’s Core ensured he ended up as a God of the kitsch B-movie.

Yet Keeler says a big reason why Cushing, who has an exhibit in his museum, became so accepted into the Kent seaside town was due to the humble way he’d poke fun at his own mythology. “We owned a corner shop near the sea wall and I remember Peter came in one day,” he continues. “I told him I had taken the sticker off his chocolates, so the recipient wouldn’t know the price. He replied: “Elementary, my dear Watson.””

Wearing a battered deerstalker, yellow bow tie and light blue tweed jacket with smoking gloves in its pockets, Cushing looked like he’d stepped out of another era entirely. In person, he was a dapper, if slightly more musty and weathered, extension of his well-spoken Dr. Frankenstein character in the Hammer Horror films. During an awkward interview with British TV’s Richard and Judy, the latter mistakes Cushing’s suit – eccentric by 1991’ standards – as being something from a gothic film set. He politely kisses Judy’s hand at the end of the interview. “That was all him,” clarifies Keeler. “Peter was what I consider to be the last of the true Victorian gentlemen, not too dissimilar from the intellect of his Sherlock Holmes character but much, much warmer.”

Meeting that magic, blue-eyed stare (which earned Cushing the nickname “Bright Eyes” from friends and family) is said to have made all your hairs stand up, as the soft-spoken actor elegantly whizzed past you in the town centre on a red, big-wheeled, Adler-style bicycle that wouldn’t have looked out of place in the 1940s. It’s likely Cushing was en route to his beloved Tudor Tea Rooms to meet his personal assistant Joyce Broughton for a brunch of boiled eggs and toast soldiers, before riding off on the “sit up and beg” bike for a daily coastal pilgrimage to nearby Seasalter, where Cushing, who had an encyclopedic knowledge of British wildlife, playfully sang to the birds. At the ancient church of St Alphege, he quietly reflected beside the grave of Helen: his beloved late wife and creative muse who died in January, 1971, after a long battle with emphysema that had derailed her own acting career.

“Without fail, he’d always say “Hello, dear boy!” says 65-year-old Lawrence Bradley. He grew up on Whitstable’s Sydenham Street and became acquainted with Cushing when his father (who took up the plot next to Helen’s in the graveyard) died. The pair shared a deep mourning. “When I’d bump into him at the grave, I always felt bad, like I had just interrupted a private conversation.”

Of why Cushing meant so much to Whitstable, Bradley offers, unprompted: “Peter gave the whole town this incredible feeling of pride, just by being here. We really loved him, because legendary actors don’t typically choose to live by the seaside in Kent. He chose us.”

The word “legendary” doesn’t feel like hyperbole when it comes to Cushing. Over a 60-year-plus career, the actor – born in Kenley, Croydon in 1913 and dead by the summer of 1994, at 81, following a prolonged prostate cancer struggle that started in the 1980s – lit up the screen. He was often typecast as villainous characters, but they were so deliciously evil that you secretly hoped they’d somehow find the upper hand.

As the Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars, a role of which he was rumoured to have been paid just £2,000, he treated Darth Vader like his personal Rottweiler while jovially signing off on the use of a deep space nuclear weapon like a Lord ordering smoked salmon for lunch. The terrifyingly efficient character was so powerful that Cushing was impossible to recast and so brought back after death, with a CGI-version making the air chill in Star Wars prequel Rogue One (2016). Cushing, a great believer in the afterlife both on and off-screen, surely would have smirked at the idea.

Horror is where Cushing really soared. In British studio Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), where Cushing plays the titular Doctor, the sadistic smile he flashes just seconds after reanimating Christopher Lee’s twisted corpse into a Monster is impossible to forget. It’s been imitated but rarely bettered by other big screen anti-heroes, including Tom Hiddleston (who even looks like a younger, more brawny Cushing) as Marvel’s Loki. Cushing and Lee (who died in 2015 at 93) would also memorably duel on screen as a resourceful Van Helsing and a blood sucking Count in Dracula (1958), delivering hammy camp dialogue with Shakespearian poise while waging wars with just a stare. They remained friends right until the end and proved, as a duo, that British horror could be a force to be reckoned with.

In these films Cushing was an unlikely sex symbol, and despite committing acts of brutal murder and often coming across as a sadist, the actor effortlessly charmed the socks off his buxom female co-stars. A natural flirt, Cushing admitted in a later TV appearance that he carried a deep guilt for carrying out extra-marital affairs. According to Sherlock writer and British actor Mark Gatiss, the fact the multi-faceted Cushing was so associated with horror negatively impacted his career trajectory; a reason perhaps accounting for the fact he didn’t have a cabinet full of film acting awards.

“Thanks to a combination of sincerity and a slightly manic edge [as an actor], I don’t think anything suited his gifts more than horror,” Gatiss said in a radio interview. “He left us a fantastic legacy in an area [and genre] often looked down on, which perhaps stopped him from being elevated to the top flight of film actors.”

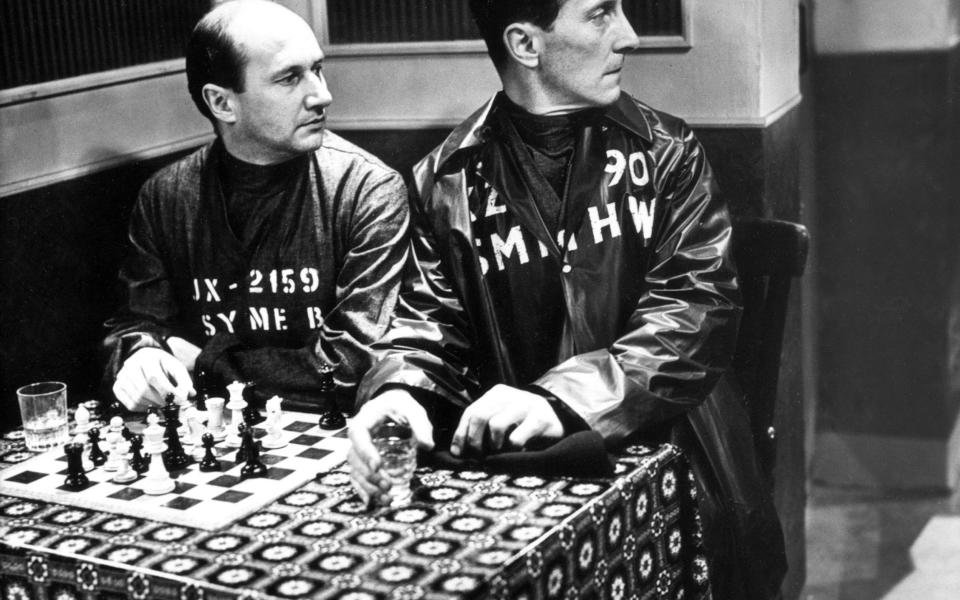

But Cushing didn’t confine himself only to the horror genre. In fact he was so versatile BBC producers called him “the maid of work” and the actor succeeded in playing ordinary, everyday characters that you wanted to console with a hug. In 1961’s Cash on Demand, a film about a Scrooge-like bank manager, Harry Fordyce, who is told to empty a safe of money or have his family shot back at home, Cushing plays the character as a sweaty, shivery wreck. He forces you to empathise with this socially inept snob, joking: “It’s been a hard day so far” with that characteristically sharp wit. In this film his gaze has its own language, feeling like he’s sharing the pain of the character with audiences telepathically.

Not finding big screen fame until his forties, something his tough-to-please father, George, openly mocked over family dinners, Cushing’s pre-film career was moulded as a working actor in the theatre both home and abroad. Shifting between an introverted bag of nerves, who often escaped into his own imagination, and being the biggest charmer in the room, Cushing hustled his way up from cleaning the aisles as theatre manager at Worthing’s Connaught to acting besides Lawrence Olivier on an Old Vic tour of Australia and New Zealand. The connection with mentor Olivier led to a role as Osric in his Oscar-winning film production of Hamlet in 1948, giving Cushing confidence to keep faith with acting.

Yet it was finding soulmate Helen Beck that really kept Cushing going. He first fell in love with Helen, a fellow travelling actor, in 1942 during a tour of Noel Coward’s Private Lives that played at various military hospitals. They would marry a year later, barely making ends meet but happy together. “There was an aura about this beloved vagabond,” she wrote in a diary entry shared in Cushing’s autobiography.

The pair performed during the Blitz, Cushing writing in the same autobiography of an occasion where the pair calmly kept in character during a show despite constant bombs falling outside. Helen willed the naturally insular actor to come out of his shell, leaving encouraging letters around the house and telling Cushing to envision he had played the Rugby World Cup final for England when despairing over losing some of his front teeth (Cushing did all of his own stunts) and having to wear false ones during a scene. One of the letters reads: “Peter, you are unaware of your own value, and what your name means to the people.”

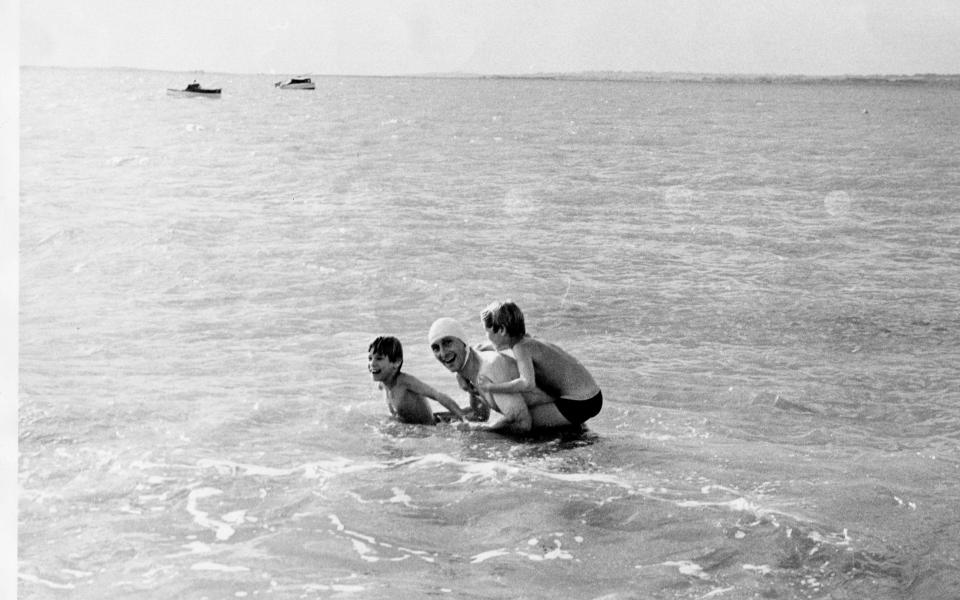

Eight years older than Cushing, Helen suffered from emphysema. As her condition worsened, their holiday home at Whitstable became more and more of a base, thanks largely to the restorative sea air and support of the friendly locals. In his autobiography, Cushing writes of enjoying “mischievous” swims with Helen and the two twins next door, William and Geoffrey Hughes, on what was once a fairly private, quiet stretch of pebbled beach. “He would take us out to swim and then buy us vintage coins and ice creams after. Peter was so, so charming,” recalls William Hughes, now in his sixties, who still lives in the same house just a few doors down from Cushing’s 3 Seaway Cottage on Wave Crest. “I remember him talking to my dad about buying the house; now tourists come to take photos of it.”

One of the only people left alive who can recall both Peter and Helen, he adds: “Helen was the kindest person you could possibly imagine. I just sensed she completed Peter. She provided him with belief, as an actor’s life requires a lot of travelling. There’s a lot of self-doubt. Peter was lonely on the road. I guess he knew he had real stability to come home to, and you could just tell he absolutely adored her.”

Helen died from the chronic breathing condition in 1971, leaving one final letter to her husband. It read: “Let the sun shine in your heart. Do not pine for me my beloved Peter, because that will cause unrest. Do not be hasty to leave this world because you will not go until you have lived the life you have been given. And remember. We will meet again when the time is right. That is my promise.” She had forgiven him for the other women.

The Neighbour says the change after Helen’s death was huge. “I saw this hunched up little figure walking across the golf court. Peter walked past the window with his head down, his face buried under the white hat he wore. This man had been a huge star in his day, but he looked so lonely and lost.”

By all accounts, Cushing rarely ventured out the house in the 1970s, keeping well insulated inside, where he’d endlessly craft beautiful sculptures of all the legendary theatres he played in, write a book about the inner peace gained from bird watching, and paint the Garden of England from his beautiful seaview, occasionally joined by English water painter and friend, Edward Seago. He was deeply consumed by grief and later admitted to walking up and down the stairs to try to encourage a heart attack so he’d be reunited with his wife. Yet, ironically, it had the opposite effect, making him even fitter.

In the years directly after Helen’s death, Cushing acted in the biggest sci-fi film of all time, sang and danced with Morecambe and Wise, and buried himself into acting work as a form of escapism. Some of these performances were particularly close to the bone, with 1972’s Tales From The Crypt featuring Cushing as a lonely widower, misunderstood by locals. Only a few months on from Helen’s death, the actor’s eyes are subsequently black with exhaustion. Yet, against all the odds, the gaunt actor delivers a stunning performance, channelling the heartbreak and isolation that comes with losing the love of your life. “We’ve always got each other, haven’t we dear?” Cushing’s character says into the abyss of an Ouija board, clearly channeling real-life loss and barely holding it together. Even if the film itself is silly, Cushing’s brave performance remains profound to anyone who has ever grieved in solitude.

One thing that was a constant, and brought real pleasure to Cushing during this otherwise bleak period, was eating at the local Tudor Tea Rooms. The traditional café’s owner Susan Fitchie, who has been working there for the best part of 40 years, cries to me while remembering a dear friend, who even showed up at her wedding.

“Some celebrities would have got angry if they were bothered in public, but Peter would have a conversation with just about anyone,” she says. “Whoever served him his meal would always get a beautiful handwritten letter or poem afterwards, too, where he’d talk about their kindness and how it had made his day. Some of these waiters are now in their forties and they consider these poems a highlight of their life.”

Fitchie shows me a never-ending pile of notes and poems, nearly all signed “from Peter and Helen”, despite his wife long being dead. “Helen stayed close to his heart. He also drew gorgeous caricatures of the diners, which we’d then sell and donate to charity,” Fichie says. “Sometimes, on doctor’s orders, he’d be forced to eat a bit of roast pork and apple sauce, just to fatten up for a role, because he was too skinny. This person saw and sold the story to the papers, angry because Peter was supposed to be a vegetarian.”

The Tudor Tea Rooms remains a shrine to the actor with framed poems and photographs at every turn. It’s largely untouched from when Cushing would visit and quietly observe the tea drinkers around him, remaining a vessel to another era. “If the attention ever got too much, I’d let him out the back door with some toasted tea cakes,” Sue says lovingly. “I think he learned ticks from all the people he would observe. It meant the people of Whitstable came out in all his film performances.”

With the café helping Cushing re-integrate into the Whitstable community after Helen’s death, the rejuvenated actor would help with a campaign to save Chatham’s Central theatre and lend a hand to local Marika Cavell’s project to sneak a mix of Romanian and Hungarian orphans into Faversham for a holiday, so they could briefly escape poverty and enjoy the British seaside. “When the children arrived, Peter told me to take the kids to this little shop called The Magic Wardrobe, where he had arranged seaside gifts for every last one of them,” the now 80 year old recalls, herself once a child refugee from Budapest.

“He was so patient and gentle. I remember they were sat in his garden, which was a humble garden and nothing like a Hammer Horror mansion, singing a Hungarian folk song under this sprawling willow tree. He gave a rose to one of the girls, because her smile reminded him of Helen’s. He was practising for a new cowboy movie, so he showed the boys how to aim with a toy Magnum. It was an experience I’m sure none of them ever forgot.”

This was towards the end of Cushing’s life as he continued his battle with cancer. It visibly took more and more out of the alarmingly thin actor. In those final years, the town honored him with Cushing’s View, a plaque beside one of the actor’s favourite beach-side relaxation spots. Keeler tells me a story of an out-of-town tourist aggressively asking locals where the greying Cushing lived in the early 90s, with each giving him a different wrong answer. “They were protecting his privacy, like he was one of their own,” he explains.

Cushing died from cancer in a hospice in Canterbury on August, 11, 1994. At his funeral, thousands of locals lined the streets. It was packed. His rotting house has rarely changed since his death, clearly in need of renovations and its windows hidden by overgrowth. It’s unlikely Cushing would have recognised the Whitstable today, which has been infiltrated by migrating Londoners, expensive seafood bars, and lost a lot of the quietness and space that the actor once enjoyed.

It’s also debatable whether the actor, who was more fond of John Player cigarettes than alcohol, would have liked a Wetherspoons’ pub named after him. However, the ugly boozer is housed in the Old Oxford Cinema, which would have at least once have shown Cushing’s films. Many locals believe the actor, who was awarded an OBE in life, deserves a more permanent tribute, such as a statue or a theatre in his name.

According to Cavell, if you concentrate hard enough, it’s easy to zone out from the hustle and bustle of the increasingly overpopulated yet picturesque seaside town and tap into Cushing’s calming presence. Sometimes, she imagines him cycling through the Whitstable streets, moving to that jolly whistle. “Whether Peter would recognise modern Whitstable or not doesn’t matter, because he’s woven into the fabric of this town now,” she says. “They’ll be telling stories about him in the pubs and cafes here forever.”