Hollywood's king of mean: the bald truth about Yul Brynner

Yul Brynner won a best actor Oscar for playing King Mongkut of Siam in the 1956 film version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I. The film remains banned in Thailand because the monarch was portrayed as vain, bad-tempered and autocratic – all words that could equally have applied to Brynner. He played the role 4,625 times on stage and admitted “the king takes me over”.

Although Mongkut remained his greatest role, Brynner, who died in 1985, also starred in celebrated films such as The Ten Commandments, The Magnificent Seven and Westworld. Tales of his egotistical, demanding nature followed him around, and he had bitter rivalries with fellow actors, including Steve McQueen and Ingrid Bergman.

The year Brynner won his Oscar, the best actress trophy went to Bergman, for her role alongside Brynner in Anastasia. She recalled his churlish behaviour on set. When they were introduced, the Swedish actress, who was a couple of inches taller than her co-star, asked whether he would prefer to use a prop in their scenes to conceal their height disparity. He fixed her with a gimlet stare and hissed, “I am not going to play this on a box, I’m going to show the world what a big horse you are.”

Paranoia over size also played a part in his disputes with McQueen four years later during The Magnificent Seven. Brynner reportedly fashioned a small mound of earth to stand on during his scenes with McQueen, so that he would appear to be the taller man, even though he was giving away a couple of inches. In retaliation, McQueen would surreptitiously kick over the dirt whenever possible. He would also try to upstage Brynner by playing with his gun, or repeatedly fiddling with his cowboy hat while Brynner spoke lines.

According to co-star Eli Wallach’s autobiography, Brynner even hired an assistant to count the number of times McQueen touched his hat while Brynner was speaking. “We didn’t get along,” admitted McQueen. “Brynner came up to me in front of a lot of people and grabbed me by the shoulder. He was mad about something. He doesn’t ride well and knows nothing about guns, so maybe he thought I represented a threat. I was in my element. He wasn’t. When you work in a scene with Yul, you’re supposed to stand perfectly still, 10 feet away. Well, I don’t work that way. So, I protected myself.”

Brynner encouraged mystery over his origins, joking that “there are 10 or 12 stories in circulation about my early life,” including his father’s supposed Mongol origins. Brynner sometimes claimed he was born Taidje Khan, on Sakhalin Island, off the coast of Siberia. Later biographers confirmed that he was born Yuliy Borisovich Briner in Vladivostok. Brynner also gave conflicting information about the year he was born, variously citing 1915, 1917, 1920 and 1922. He declared imperiously that “ordinary mortals need but one birthday”.

His real birthdate (July 11 1920) was confirmed on his tombstone. His habit of spinning yarns never left him. Among his many tall tales were those about having fought for the International Brigade during the Spanish Civil War.

After his father Boris, a mining engineer, abandoned the family, Brynner grew up in Beijing. “He always spoke of his father with bitterness,” said Yul’s daughter Victoria. In 1932, to escape China’s war with Japan, Brynner’s mother Marousia took her son and his elder sister Vera to Paris, where his life of adventure began. After leaving school at 16, he played guitar in a travelling Gypsy troupe before working as a trapeze artist with the Cirque d’Hiver.

His time as a circus acrobat came to an end in 1937 when he fell from the parallel bars, suffering 49 different fractures. As he recovered, the multi-lingual Brynner (he spoke English, French, Japanese, Hungarian and some Russian) turned his attention to the stage, an ambition that prompted his move to America in 1940. It took a decade of scuffling around – a time that included driving the bus for an actor’s company, playing small roles on Broadway and working as a French-speaking radio announcer for the US Office of War – before he made it big.

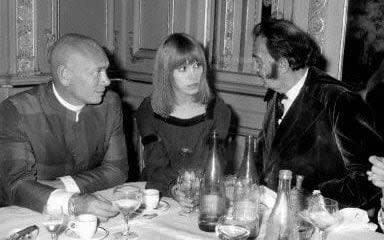

During that time, Brynner had a passionate affair with the actor Hurd Hatfield – best known for playing the title role in the 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray – and posed for naked full-frontal portraits for the noted gay photographer George Platt Lynes. Brynner, who would go on to have four marriages and a string of affairs with high-profile actresses including Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, and Joan Crawford, never publicly admitted his bisexuality. His male affairs, including, it is claimed, with poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, were kept out of the press, who instead presented an image of a man happily married to the actress Virginia Gilmore.

When Brynner auditioned for The King and I in 1950, he was told that the production was a vehicle for Gertrude Lawrence, who was starring as Anna, the English governess to Mongkut's children. At first, the audience reaction to Brynner was far from positive. Years later, he recalled that one angry spectator threw a shoe at him on stage. “And it was a perfectly serviceable shoe,” Brynner joked. “The man must have really hated me.”

However, his performances were so mesmerising that audiences were soon flocking to see him. Brynner had been proud of his long locks – he claimed his hair was so luxuriant that he had not needed a fake wig to play a clown in his circus days – but he decided that shaving his head to fully resemble a Siamese monarch would attract more publicity. The stunt worked and he remained hairless for the rest of his life.

In March 1952, Brynner won a Tony award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical, which increased his resentment about not being listed as the main star of The King and I. In August 1952, Lawrence fainted backstage after finishing a Saturday matinee performance. She died within a couple of weeks. According to Ken Bloom’s Show & Tell: The New Book of Broadway Anecdotes, Brynner burst into tears when he heard the news – although his weeping was prompted not by grief but by the sudden realisation that he would now get top billing.

After the movie version of The King and I, Brynner’s piercing gaze, arched eyebrows and bald head became famous throughout the world. “Yul’s work in The King and I was beyond compare,” said Charlton Heston. His already over-sized ego seemed to explode. He decreed that he would not be photographed next to any other hairless actors – telling his press agent “no pictures with baldy!”.

Accounts of his boorish behaviour around this time were included in in Frank Langella’s 2012 memoir Dropped Names: Famous Men and Women as I Knew Them. “Yul was never far from a full-length mirror, and the word ‘I’ passed Yul’s lips more often than perhaps any actor I have ever known,” wrote Langella, who was starring as Dracula at the Martin Beck Theatre when The King and I was playing at the St. James Theatre.

Langella’s most disturbing tale concerned Brynner’s racial prejudice. Brynner gave Langella and his wife Ruth a lift in his 20-foot-long white limousine. “He demonstrated all the gadgets the car had,” recalled Langella. “He picked up a large pair of strobe lights, aimed them at us, and clicked twice, temporarily blinding our vision. ‘This is in case blacks attack my car,’ he said. ‘I shine these at them and click many times. They think they are being photographed and run away.’”

Brynner also told Langella he’d instructed the theatre to build a special lift that was big enough to accommodate his car, so that he could be driven straight in without having to interact with the public. Langella said Brynner would often complain about his audiences, telling him one night, “they were sh-t. I would not bow. I gave them my ass.” When he returned to playing Mongkut in the 1980s, he boasted about how he humiliated noisy theatre-goers. “We had some giggly ladies, who probably had too many martinis before lunch, so I told them to ‘shut up’. The theatre is my palace and I can tell them what to do.”

By then, his reputation as a tyrant was known throughout the theatrical world. There were numerous tales of the vicious things he said to production staff or the times he threatened to have people sacked. His was proud of his demanding nature. “I am merciless about things in the theatre,” Brynner told television host Bill Boggs. “The lazy louts should be afraid of me… any dead wood that I come across, I simply break it off.” Despite his temper, he was adamant that he had no need for psychotherapy. “The day anyone stretches me out on a couch, I’ll be either drunk or dead,” he said.

His son Yul Brynner Jr – who was known by his childhood nickname ‘Rocky’, taken from the boxing champion Rocky Graziano – admitted that his father could be difficult and “went a little crazy, at times” (Rocky, incidentally, went on to lead his own fascinating life, which included working as the road manager for The Band and Bob Dylan and being a bodyguard to Muhammad Ali).

Special effects maestro Ray Harryhausen, who worked on The Magnificent Seven, remembered Brynner as “a good actor” but also a man who was “difficult and bad-tempered, with his own set of demands”. According to Brynner’s agent Robbie Lantz, the actor’s contract demands were astonishing. He would specify the colour of the carpet in his trailer, along with the type of tissues and bottled water provided. In hotels suites, his “imperial conditions” included touch-tone telephones with 13-foot cords, blackout curtains to help him sleep, brown eggs only for breakfast and extremely expensive bottles of wine.

By the time he came to play Captain Mueller in the 1965 movie Morituri – alongside Marlon Brando as The Captain – Brynner was powerful enough to stipulate that a landing pad be built on the ship so that a private helicopter could take him ashore after each day's shoot.

Despite earning what Lantz called “astronomical” fees, Brynner gained a reputation for tight-fisted behaviour. George Jabobs, who was part of Frank Sinatra’s staff, got to know Brynner after the actor and singer became golfing friends and acted together in the big-budget 1966 thriller Cast a Giant Shadow. “Yul Brynner was hanging around, sponging off Frank for food, drink and girls… we called him Uncle Scrooge, the king of the tightwads,” Jacobs wrote in his memoir Mr. S: The Last Word on Frank Sinatra.

Brynner was an accomplished photographer and one of his most acclaimed shots is of Sinatra descending from a helicopter. He took more than 8,000 photographs, including noted ones of Elizabeth Taylor, Anthony Quinn, Sophia Loren, Mia Farrow and Audrey Hepburn, who was the godmother to Victoria, the child Brynner fathered with his second wife, the Chilean model Doris Kleiner.

In 1996, Victoria put together a collection of her father’s work for the coffee-table book Yul Brynner: Photographer. The actor also cashed in on his fame with The Yul Brynner Cookbook: Food Fit for the King and You, which included his recipes for dandelion soup and Pork and Sauerkraut Ragout.

In 1971, Brynner married his third wife, Jacqueline Thion de la Chaume, the Fashion Editor of French Vogue. She and Brynner adopted two Vietnamese children, Mia and Melody, and purchased the 16th-century, 50-acre Manoir de Criqueboeuf in Normandy – where Brynner kept a rookery of penguins.

During this period, he was sent the script for Westworld, a science-fiction thriller by Michael Crichton. Brynner was an avid reader. He studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and attended ethics classes in Chicago run by Dr. Paul Arthur Schilpp, a respected scholar who founded the Library of Living Philosophers. Schilpp described Brynner as having “one of the most brilliant minds I ever encountered”, and said the actor was “well versed in politics, economics, literature, music and history”. Brynner was proud of his work on the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees and his campaigns to stop prejudice against gypsies.

Brynner praised the way Westworld explored the theme of human “infantilism in the face of new technology”. Crichton thought the 53-year-old was perfect for the role of the cyborg gunslinger, saying “If anyone really built a place like Westworld, they probably would make the gunfighter robot in the image of Yul Brynner.”

He took the role seriously, even wearing silver-metallic contact lenses throughout filming to gain the effect of a steely robot-like stare. Richard Benjamin, who played the man Brynner’s malfunctioning robot tries to kill in the futuristic amusement park, had happy memories of their time together. “Yul Brynner was just the best,” Benjamin said, “and he taught me how to fire a gun in a movie and not blink. He said, ‘You look at the biggest Western stars, and I’ll show you that they blink when the gun goes off.’ He was a pretty amazing, larger-than-life person.”

Westworld was Brynner’s last great movie role – his final appearance was in the Italian Western Death Rage in 1976 – and he expressed regret that he was unable to fulfil his dream of making a film about Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. “I would have needed 20,000 men to re-create his battles,” Brynner said. “The Turkish Government agreed to that, but no one could agree about the facts of his life.”

Instead, he reprised Mongkut in endless tours and Broadway reruns of The King and I. Mary Beth Peil, Brynner's leading lady for the final two years of the touring production, said she was warned before meeting him that she was never to touch him or look straight into his eyes. Instead, he surprised her with a big hug and told her, “welcome to the family.”

Brynner took up smoking at the age of 12 and eventually consumed five packets a day. In 1983, the year in which he married his fourth wife, a 24-year-old Malaysian chorus line dancer called Kathy Lee, Brynner was diagnosed with throat cancer. Facing his doom, he embraced Buddhism and said he finally understood the reality of the “Gypsy saying” that “your future is getting shorter”. He was 65 when he died on 10 October 1985, shortly after completing a triumphant return to Broadway.

One of his last acts was to record a commercial for the American Cancer Society, which was broadcast after his death, warning that “now that I’m gone, I tell you: don’t smoke, whatever you do. Just don’t smoke.” His message from the grave was credited with persuading thousands of people to quit smoking.

In typical Brynner fashion, the actor gave lots of different versions specifying what should be written on his headstone, including the words “I have arrived” and “here lies a man who adored children of all varieties.” His remains reside in a Loire churchyard in France and the only words on the headstone are his name and the dates of his birth and death. It was one contract demand that went unfulfilled.