How Jane Asher – and her mother – changed Paul McCartney, and inspired some of his greatest songs

The first snippets from Paul McCartney’s mammoth new book about his songs – and the stories behind them – appeared at the weekend, and there were some fascinating nuggets. We learnt, for example, how the “guarded” John Lennon only started warming to his songwriting partner when McCartney got a dog called Martha (the subject of Martha My Dear), and how the title for the Sergeant Pepper album came to McCartney after he misheard a request to pass the “salt and pepper”. If these stories are already wholly or partially known, McCartney gives them fresh life and colour.

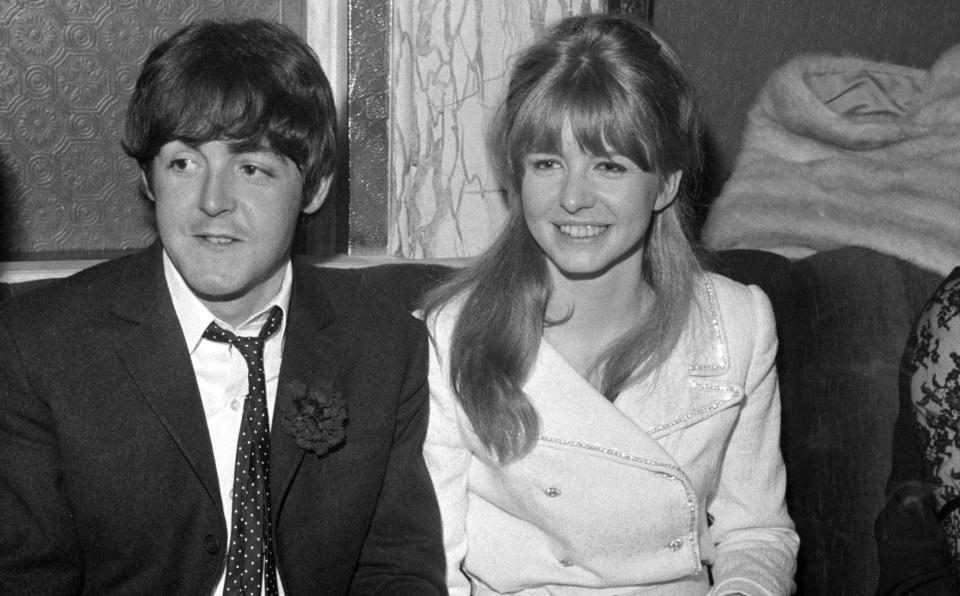

But one of the most interesting revelations in the extracts from The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present was the enormous influence McCartney’s former fiancee Jane Asher and her mother Margaret – a music teacher – had on the Beatle’s songwriting.

The then 21-year-old met Asher in April 1963 and, within months, had moved into her family home in Wimpole Street, in central London, where he stayed for three years. This, says McCartney, opened a door into a new world. “I loved it [at Wimpole Street] because it was such a family. Margaret and I got on very well. She sort of mothered me. It was what I’d been used to before my mum died, when I was 14, though I’d never seen a family like this. The only people I’d seen were working-class Liverpool. This was classy London: all of them had diaries that stretched from eight in the morning to six or seven at night.”

Erudite, warm and cultured, the Ashers had pianos in both attic and basement, and it was during McCartney’s years at Wimpole Street that he wrote some of his most intimate and famous songs. I Want to Hold Your Hand, And I Love Her and We Can Work It Out were among the many tracks written there. And it was Jane and Margaret – the well-mannered, ambitious actress and her caring, discerning, highbrow mother – who would, directly or indirectly, be their inspiration.

What popular culture might look like today if a 17-year-old Jane had not helped write an article for Radio Times magazine on April 18 1963 hardly bears thinking about. The Beatles had made their live debut at London’s Royal Albert Hall the same day and met Asher while posing for photographs.

Asher had appeared in films and TV shows including Mandy, The Quatermass Xperiment and an adaptation of Mark Twain’s novel The Prince and the Pauper. She was also a regular guest on TV music panel show Juke Box Jury, so was known to the band. After the show she accompanied the band to a party in a King’s Road flat belonging to NME journalist Chris Hutchins.

“We all fancied her,” McCartney has said. At the party Lennon – high, drunk or both – became increasingly bawdy and insulting towards Asher. McCartney took her under his wing. According to numerous accounts of the evening, McCartney and Asher spent hours sitting innocently on a bed talking about their favourite food. Keen to impress his well-read companion, McCartney then quoted a line from Chaucer’s The Prioress’s Tale in its original Middle English. A bond was forged.

McCartney and Asher embarked on a relationship that lasted over five years and, while living with her family, started to see Margaret – the oboe professor at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama – as a second mum. Jane’s father, meanwhile, Dr Richard Asher, was a respected psychiatrist who had named and identified the mental disorder Munchausen’s Syndrome. Her brother Peter was in pop duo Peter and Gordon (who went on to have a number one with A World Without Love, written by McCartney).

The Liverpudlian loved life in the roomy townhouse, and would spend long evenings with the family, sitting around the dining table, talking, debating and listening to music. They went to the theatre. But while Wimpole Street introduced McCartney to high culture, it also fired his baser instincts. He wrote I Want to Hold Your Hand in late 1963, when he was with Asher. “Eroticism was very much the driving force behind everything I did. It’s a very strong thing. And, you know, that was what lay behind a lot of those songs,” McCartney writes in The Lyrics. I Want to Hold Your Hand was not written specifically about Jane but McCartney says he might have been “drawing on my own experience with the person I was in love with at the time...But mostly we were writing to the world.”

Months later, in early 1964, McCartney wrote the ballad And I Love Her in Wimpole Street’s basement. Again, the song reflected his happiness. It contained the lyrics: “A love like ours / Could never die / As long as I / Have you near me.”

He has remembered playing it in the Asher’s upstairs drawing room. Impressed, Lennon called it McCartney’s “first Yesterday”. However, things soured the following year. Three of McCartney’s songs for 1965’s Rubber Soul sessions suggested that all was not well. I’m Looking Through You’s assertion that “love has a nasty habit of disappearing overnight” hardly suggests harmony. You Won’t See Me, meanwhile, was written in the Ashers’ basement after Jane had agreed to appear in a play at the Bristol Old Vic. McCartney wasn’t happy and they argued. But his most starkly confessional song from the era was We Can Work It Out, which didn’t appear on Rubber Soul but was released as a single.

We Can Work It Out sees McCartney pleading with Asher to “try to see it my way”. As McCartney explains in The Lyrics: “Things were not going so smoothly between Jane Asher and me”. They’d had a row – “normal boyfriend-girlfriend stuff” – and he wrote the song in the immediate aftermath as he tried to “figure my way out of feeling bad after [the] argument.” Harrison’s idea to set it to a waltz pattern gave the track “friction and fracture”. The song remains one of McCartney’s greatest. Perhaps McCartney’s most famous song, Yesterday, also came to him in a dream in the Wimpole Street house.

None of this should detract from Margaret’s influence on the young songwriter. More a guiding presence than a direct muse, Margaret – who had taught Beatles producer George Martin to play the oboe at Guildhall – nonetheless had a profound impact on McCartney. Her love of classical music is credited with giving him the confidence to write chamber-influenced songs like Eleanor Rigby. She taught McCartney how to play the recorder, which he did on Fool on the Hill.

McCartney and Asher moved into his house in St John’s Wood in 1966 and they announced their engagement on Christmas Day 1967. Asher accompanied the Beatles on their spiritual retreat to Rishikesh in India early the following year.

But things didn’t last. In the summer of 1968 Asher returned to their London home from an acting job to find McCartney in bed with Francie Schwartz, an American scriptwriter. Shortly after, Asher announced on a TV chat show that her engagement to McCartney was over. “We still see each other and love each other, but” – perhaps reflecting his lyrics of three years earlier – “it hasn’t worked out,” she told host Simon Dee.

Fifty-three years later, McCartney still sounds both fond and rueful. The fracture he intimated in We Can Work it out “was real”, it turns out. “Sadly, Jane and I did break up. And that meant breaking up with her mother too… Now I’d lost a mother for a second time,” he writes in The Lyrics.

The warm Wimpole Street love-in was over. But what songs emerged. McCartney’s loss was pop music’s gain.

The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present (Allen Lane, £75) is published on November 2