How Peter O'Toole was struck by the curse of Macbeth

The critic Sheridan Morley once described leaving the Old Vic at the end of its 1980 Macbeth and overhearing two audience members on their way out. “One of them turned to his friend and said: ‘Well all I hope now is that the dog has not been sick in the car.’ I thought that was the best review of that production I’d ever heard.”

Starring Peter O’Toole, that Macbeth was the kind of car crash from which few actors’ reputations emerge unscathed. It left audiences clutching their sides with laughter, the press stoking up a whirlwind of contempt and O’Toole sick to his stomach with self-inflicted humiliation. The scale of the disaster paradoxically made it the hottest ticket in town but it stalked O’Toole to his grave and remains to this day a textbook instance of the “curse” of the Scottish play.

How did the great calamity come to pass? Towards the end of the 1970s, O’Toole’s star was fading. The tepid reaction to his historical epic Zulu Dawn (1979) highlighted the distance travelled since the heroic heights of Lawrence of Arabia in 1962. Yet he was still a box-office draw and he looked back proudly on his Shakespearean endeavours – a sensation as Hamlet at the Bristol Old Vic in 1958, he had reprised the role in 1963 for Laurence Olivier (albeit to less acclaim).

When, in an interview, O’Toole indicated his wish to venture back on to the London stage, director Toby Robertson, who ran Prospect, a touring company based at the Old Vic, got in touch and the pair struck an accord. The actor, then 47, was made an associate director and granted his own office on site. The initial plan was to tackle Uncle Vanya too but O’Toole’s health, wrecked by years of hard drinking (and a major stomach operation in 1975 that had forced him to give up alcohol), wasn’t up to it; he stormed out of a meeting when the issue was raised. Eventually it was agreed that all the focus would go on a play that O’Toole had a horror of naming (referring to it as “Harry Lauder”); from that moment on, a mist of misfortune descended on the project.

Robertson was ousted from his post by the theatre’s board (at the behest of the Arts Council, concerned by the company’s deficit). In his stead stepped the actor Timothy West who, returning from a brief film shoot in the States, was aghast to discover that O’Toole had been granted total artistic control of the production by his predecessor. There was to be no reneging; if so, O’Toole’s lawyers threatened to sue the company. Jack Gold pleaded a release from his commitment to direct, and was granted it.

As West recounts in his 2001 autobiography, A Moment Towards the End of the Play, O’Toole had one jaw-dropping suggestion for the design: portable inflatable scenery. A demonstration by its Irish maker is described thus in West’s book: “Our ears were suddenly assailed by a noise as if of a gigantic vacuum cleaner operating at full tilt… The curtain rose to reveal a dimly lit collection of black plastic phalluses swaying in the wind… The general effect was of a blustery day during a refuse collection strike.” To his credit, O’Toole realised it was a non-starter; instead, the replacement director (Bryan Forbes, a man of the screen not stage) exhumed the old set from his film The Slipper and the Rose from Pinewood.

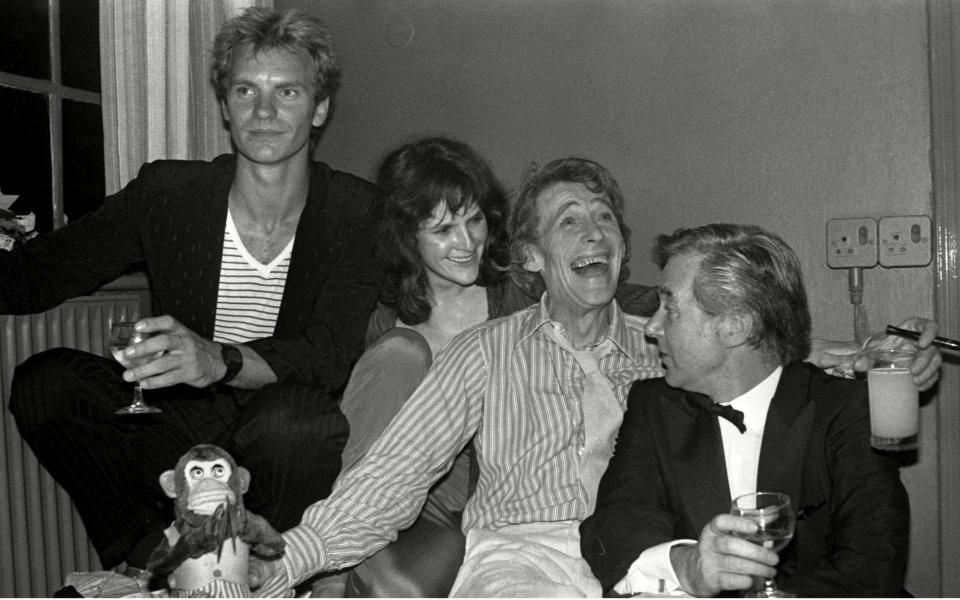

Having spent weeks memorising his lines while lugging logs of wood along the beach outside his home in Clifden, Connemara, O’Toole arrived at rehearsals word-perfect and told Forbes not to direct him until the third week. In the cast was Frances Tomelty – then married to Sting – as Lady Macbeth (O’Toole’s original, impractical thought was Meryl Streep, with John Gielgud as Duncan). Among the supporting roles was Christopher Fulford, as Donalbain, who remembers the star walking on stage at the press launch accompanied by a band of Irish pipers. One of the ensemble, Kevin Quarmby, was struck by the haggard apparition: “My immediate thought was, my God this guy looks old. Incredibly lined and thin.” As for the “midnight hags” themselves, the three witches were to be played as young seductresses – one of them, indeed, Trudie Styler (who herself later married Sting) had an affair with O’Toole.

West – referred to by the increasingly paranoid roué as Miss Piggy – was banished from rehearsals but was horrified by the much-postponed protracted run-through: “There was no evidence of any thought having been given to the play.” On the opening night, Sept 3 1980, he watched the audience troop in, and grimaced, “powerless to save the passengers as they pushed their way determinedly up the gangways of the Titanic”. A slip of paper introduced into every programme dissociated the theatre from the production.

Brian Blessed, who had only arrived to play Banquo three days before opening night (owing to prior commitments), nursed O’Toole through the ordeal. Just before curtain-up, Forbes pleaded with Blessed to get O’Toole on stage. Entering the star’s dressing-room, painted blood-red for the occasion, he was confronted by a terrified man, naked to the waist, in leggings and boots (the wardrobe department had been sacked). “He was already exhausted, emotionally and physically. Totally destroyed,” Blessed recalled. “I don’t think he was on drugs at the time, but he was certainly out of his mind with fear.” He then dragged him down the corridor, “threw him” on stage – minutes after the entry cue – and heard the audience’s silence as they registered the frightful vision.

It was after the slaying of Duncan that the laughter began. Princess Margaret, who’d dropped into rehearsals, had recommended fake blood be used for maximum authenticity, and O’Toole plunged into a bathful of the stuff. “I have done the bloody deed,” he said, and it brought the house down. There was so much slipping and sliding, the stage had to undergo an emergency clean. “Ladies and gentlemen, this is not an interval,” Forbes was forced to announce as the safety curtain fell.

At the end of a laborious three hours, the critics dashed off to do their worst. “With one flying, scarcely credible leap the Old Vic Macbeth takes us back about a hundred years,” The Guardian jeered. “Not so much downright bad as heroically ludicrous,” chimed The Mail. O’Toole put on a brave face, defusing journalists’ questions with quips along the lines that the audience hadn’t laughed nearly enough. Richard Burton told him, “F--- the critics.” Katharine Hepburn advised: “If you’re going to have a disaster, have a big one.”

O’Toole even invited the press back – and they slaughtered him all over again. The Telegraph ran a whole page on the catastrophe, and this time it made the stock market boards on Times Square. He was beside himself with anguish. Blessed found him backstage on his knees after that second drubbing: “All the veins were sticking out of his head, and I was standing in front of him gently pushing them back in… It was if his skull was open and his brain [was] hanging out of his head. He spoke as if he were about to die… ‘Brian, have you seen what they’ve written about me? I can’t take it any more.’” Blessed cradled him and sang a lullaby, reassuring him that he would cancel the show. As Blessed walked off, “he followed me on all fours, like some demented ape… gripping me and saying, ‘I have to go on, Brian, please let me go on… If I don’t, I will die...’ ” That particular show lasted five hours.

To his credit, O’Toole didn’t miss a performance and even sallied forth into the provinces, playing Liverpool, Leeds and Bristol. “Is This a Success I See Before Me?” The Observer wrote, surveying the packed houses. It returned to the Old Vic, where it again played to full houses, but when it reached the end of its run, everyone involved felt relief. O’Toole resigned his associate directorship and that was that. “My nose starts bleeding the minute I even think about the reviews,” he later said of “the most difficult thing I’ve ever done”.