On screen or off, Charles Bronson was not a man to mess with

When Charles Bronson was the highest-paid actor on the planet, earning nearly £2 million per film after his hit role as the Death Wish vigilante, he bemoaned his enduring image as a volatile, brutal character. “I feel like I’m seeing myself through one of those mirrors at a carnival – long, grotesque images,” he said in 1977.

Perhaps he was protesting a little too much. Despite his sophistication – Bronson loved to relax by creating oil paintings or making clay sculptures – he lived up to director Ingmar Bergman’s description of him as “a man whose face is etched in violence”. As a youngster, Bronson threatened strangers with a bottle before robbing them, as a soldier he broke a sergeant’s arm during a brawl and he once choked a director after a disagreement over how a scene should be played. It’s unsurprising that when Aberystwyth-born Michael Gordon Peterson, AKA “Britain’s most notorious prison hard man”, chose a new name in 1987, he picked Charles Bronson.

The actor born Charles Dennis Buchinsky, on November 3 1921, had a tough upbringing. His Lithuanian father Valteris died when he was only 10, killed by “black lung” poisoning after years down the mines in Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania. This desolate coal camp, known by locals as ‘Scooptown’, was where Bronson, the 11th of 15 children, grew up. By 16 he was already toiling down the mines, earning one dollar for every ton of coal he dug.

He always spoke bitterly about these six years of “back-breaking” work, which left him with “unsightly hands” and permanent scars on his legs and torso. A legacy of labouring on his knees in pitch blackness was headaches and claustrophobia. “I’ve never gotten the smell of coal out of my nostrils,” he lamented.

Brian D’Ambrosio, who wrote the 2001 biography Menacing Face Worth Millions: A Life of Charles Bronson, said that after becoming famous, the “dissembling” actor promoted myths about his childhood to fool “gullible journalists”. He sometimes claimed he could not speak English at high school, that he was sold to travellers by his mother Mary, and that, most famously, he was forced to attend school in his sister’s clothing. “That story of Charlie wearing dresses is absolutely ridiculous,” said Bronson’s first wife Harriett Tendler. “His brothers joked a lot about Charlie’s poor made-up misfortunes.”

His flights of fancy remained after he became famous. He claimed to have been in jail twice, although D’Ambrosio could find no prison record, and avouched that he’d once been shot by a police officer on a freight train, claiming he was unharmed because “the bullet fell right out.”

What is beyond doubt is that being drafted into the army in 1943 turned his life around. The youngster who “used to stand on street corners with a milk bottle in my hand waiting to rob someone” found a purpose. Harriett said he never liked to talk publicly about his wartime exploits, although Paul Talbot’s 2015 book Bronson’s Loose Again! On the Set with Charles Bronson, included the revelation that Bronson got into serious trouble while training with the 760th Flexible Gunnery Training Squadron in Kingman, Arizona, when a sergeant started a fight with him.

“I picked the bastard up and threw him. For some screwy reason I thought that if I didn’t hit him, I wouldn’t get in trouble. So I threw him,” recalled Bronson. “When he landed, he broke his arm. I got six months hard labour, carrying sides of beef into the mess hall and cans of garbage out of it.”

After his death, on 30 August 2003, lots of newspapers, including the New York Times, wrongly reported that Bronson’s war record amounted to driving a delivery truck in Arizona. His former comrades forced retractions after confirming that Bronson had, in fact, been a war hero, running 26 combat missions in the Pacific as a tail gunner in the Guam-based 61st Bombardment Squadron.

Bronson earned two Distinguished Unit citations and a Purple Heart, after taking a bullet in the shoulder during one raid. In 1977, Bronson arranged for his old B-29 flying partner Ken Trow to play an extra in the spy thriller Telefon. Trow told The Great Falls Tribune that the man he’d known as Charlie Buchinsky had been a “real quiet, likeable guy”.

After earning an honourable discharge in 1946, Bronson worked as a baker in Philadelphia and as a bingo caller on an amusement pier joint in Atlantic City before trying to become an actor. He paired up with former serviceman Jack Klugman, later a Golden Globe winner, and in 1948 they roomed together in New York while they looked for work. Krugman recalled that Bronson was a “starving actor, selling blood for five bucks and living in one room”. Bronson, who spoke with a strong Slavic accent, remembered being shouted at for mispronouncing the word “heroine” in his first audition.

In 1949, 27-year-old Bronson married 18-year-old aspiring actress Tendler. Within two years, after studying drama in Philadelphia and Los Angeles, he began to pick up small roles in films, playing what he described as “punks, construction workers and punchy fighters”. By then, he told Newsweek in 1972: “I was already identified as a character actor by my ridiculous speech. All the leading men were Cary Grant types. I didn’t look or sound like the guy who got the girl… I looked like a rock quarry that someone dynamited.”

Bronson appeared in 31 movies in the 1950s, bit-parts alongside stars such as Gary Cooper, Burt Lancaster and Randolph Scott. One of his most enjoyable roles was playing Vincent Price’s deaf mute henchman Igor in the 1953 3D horror film House of Wax. Bronson kept the wax model of his own head from the movie and stored it in a closet, bringing it out to scare guests. He also drove his first wife mad by chewing tobacco and then hawking the juice into a spittoon he’d nabbed from the set of a western.

In his first 20 films, he was either uncredited or billed as Charles Buchinsky. His first listing as Charles Bronson was in 1954’s Drum Beat, alongside Alan Ladd. He adopted the name after seeing a street sign for Bronson Avenue, near Hollywood’s Paramount Studios, believing his new surname would remove the stigma of having an Eastern European name in an era when communist associations were damaging.

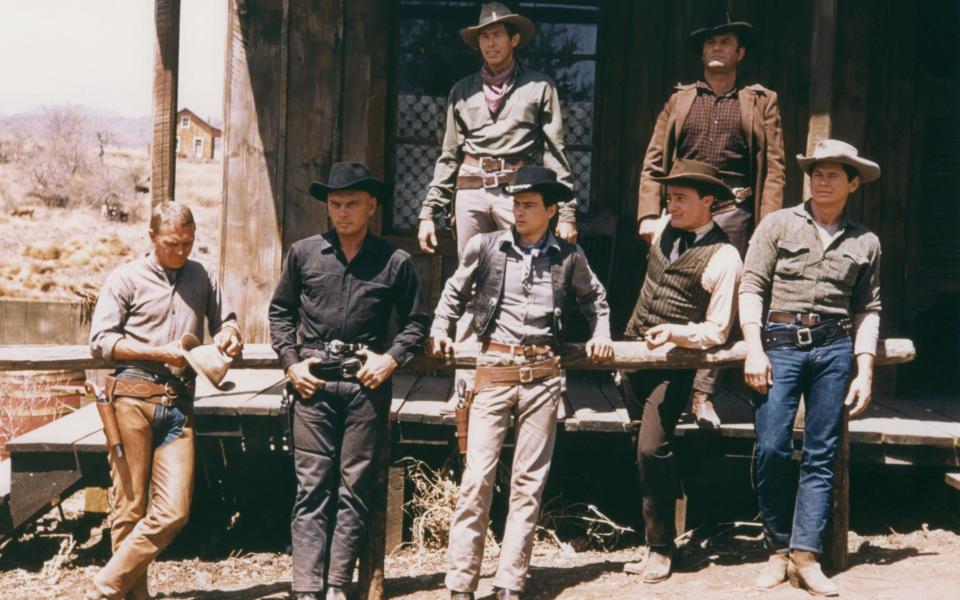

Director John Huston, who acted alongside Bronson in the 1970s, once likened Bronson’s on-screen presence, his narrowing eyes and tight-lipped mouth, “to a hand grenade with the pin pulled”. By 1960, fed up with his recurring role as Mike Kovac in the ABC crime drama Man with a Camera (“I played second banana to a flashbulb,” was how he witheringly put it), Bronson was looking for a role that would utilise the tension he brought to the screen. The opportunity came from director John Sturges, who cast him as gunslinger Bernardo O’Reilly, one of The Magnificent Seven (alongside Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Horst Buchholz, Robert Vaughn, Brad Dexter and James Coburn), in a film that was a smash hit in Europe.

Three years later, Sturges reunited Bronson, McQueen and Coburn in the prisoner-of-war drama The Great Escape. Bronson played Flight Lieutenant Danny ‘Tunnel King’ Velinski. Bronson was candid about the claustrophobia he’d suffered since his days down the mines – “even now, when I’m in the back of a car I can get those feelings,” he recalled in the 1970s – and he used his fear of confined spaces during a powerful scene in which he has a panic attack in the middle of the escape tunnel.

While shooting The Great Escape in Germany, Bronson fell in love with London-born actress Jill Ireland, then married to David McCallum. Although Bronson said later that he had “no recognition” of having told his fellow The Great Escape actor that “I’m going to marry your wife”, he realised that his marriage to Harriett, with whom he’d fathered Tony and Suzanne, was unravelling. They divorced in 1965.

By the time Bronson wed Ireland, on 5 October 1968, he had established himself as a box-office draw throughout the world, especially with The Battle of the Bulge (1965), The Dirty Dozen (1967), Adieu l’ami and Sergio Leone’s spaghetti western Once Upon a Time in The West (both 1968). Bronson was particularly popular in Japan, France and Italy, where he was called ‘Il Brutto’ (‘The Ugly One’). Ireland said she loved that nickname, as she was attracted to a man capable of “incredible tenderness” and of being “savage and primitive”.

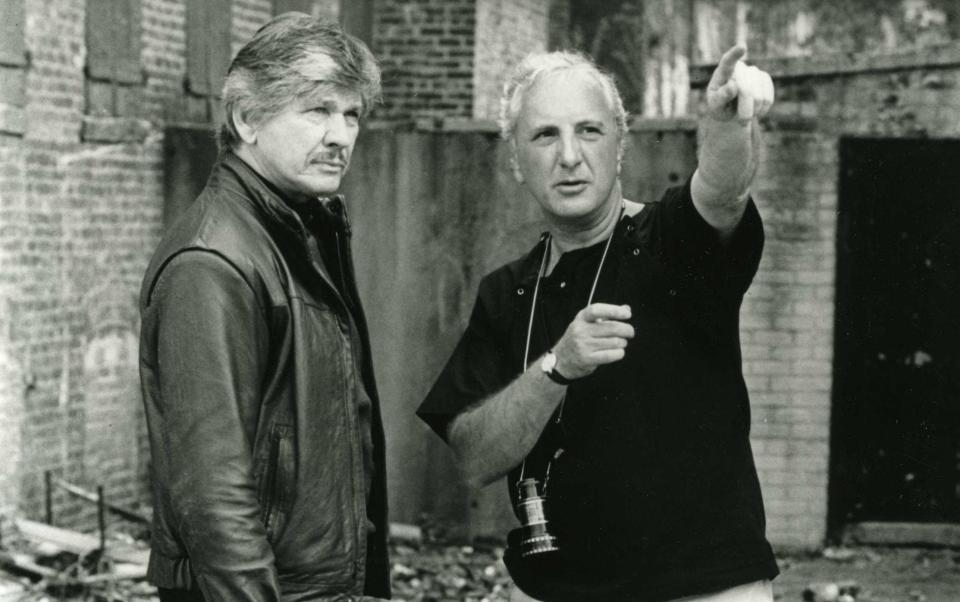

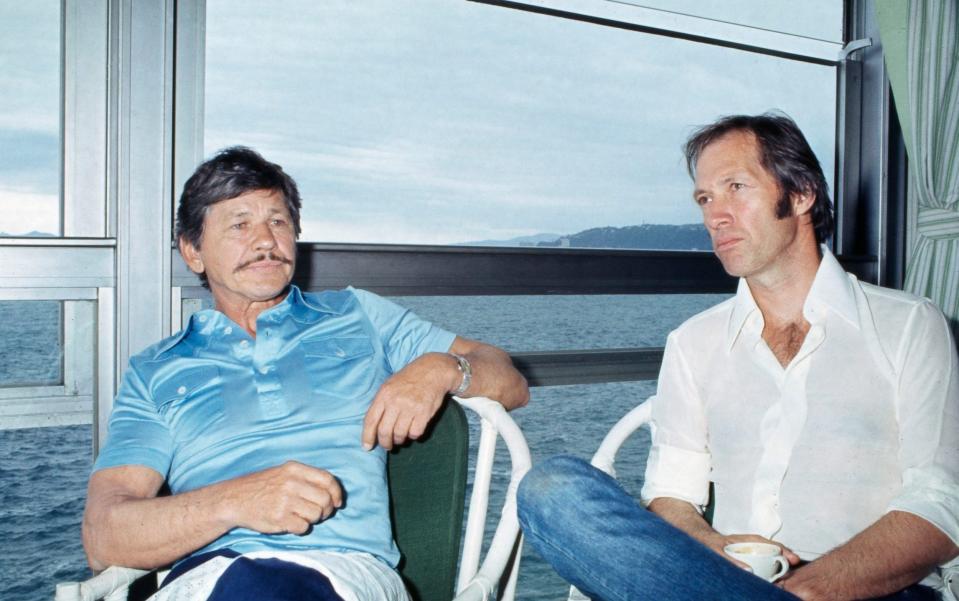

It was one of Ireland’s former lovers, film director Michael Winner, who made the most defining contribution to Bronson’s career. Winner met Bronson for the first time in 1970. He said Ireland begged him not to reveal their past affair, with Winner later remarking, “he’d probably have killed her. He’d definitely have killed me.” After directing Bronson in three films – Chato’s Land, The Mechanic and The Stone Killer – Winner offered Bronson the role of the vengeance-seeking vigilante in Death Wish, saying he was perfect because of the “repressed fury” of his character.

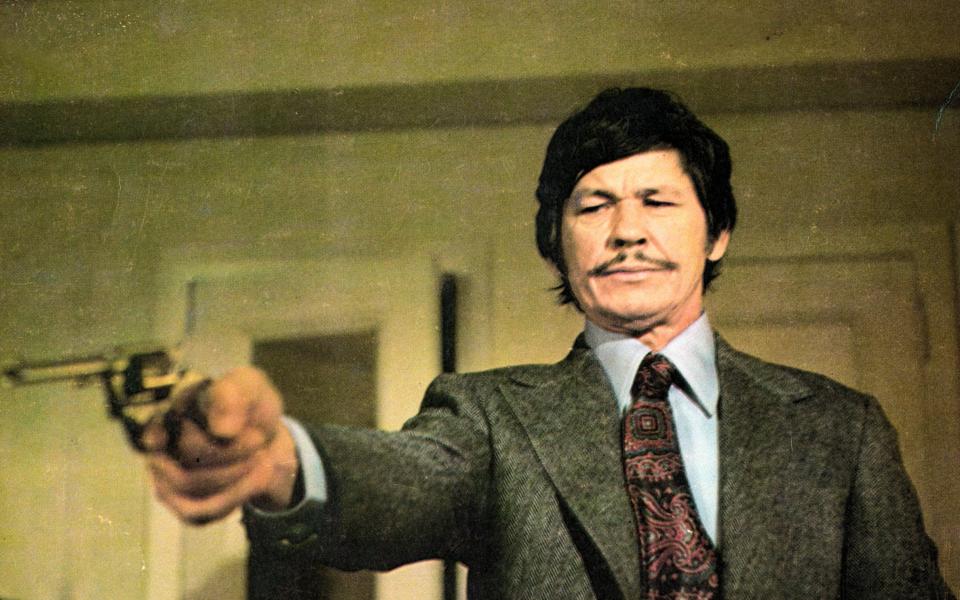

Death Wish is about New York architect Paul Kersey, who stalks the streets with his 32 calibre Smith & Wesson revolver, seeking retribution against the street thugs (one of whom is played by a young Jeff Goldblum) who raped his daughter and murdered his wife. The role, one of cinema’s most controversial, was turned down by Clint Eastwood, Burt Lancaster, George C. Scott and Frank Sinatra. When Henry Fonda rejected the role, he called the project “repulsive”.

Bronson’s agent Paul Kohner urged him not to take the part: “Paul felt strongly that it was a very dangerous picture – that it might make people think it’s right to take the law into their own hands.” Bronson was initially ambivalent, believing that the protagonist was “meek” and “suited to Dustin Hoffman”. Bronson said Winner “talked me into doing the picture”, repeatedly telling him it was a “wonderful script”. Winner remembered when he finally agreed. “Charlie said, ‘I’d like to do that.’ I said, ‘The film?’ He said, ‘no, shoot muggers’. I said, ‘no, no, no Charlie, what about the film?’ He said, ‘yeah, I’ll do the film.’”

Death Wish, which was released on July 24 1974, cost $3.7m to make and took $22m at the box office. It was based on a 1972 book by Brian Garfield, who thought Bronson was miscast as Kersey, because “you knew he was going to start blowing people away” from the moment he appeared on screen. He also judged it “a dangerous film”, believing it would inspire the public to commit vigilante acts.

Garfield, who died in 2018, originally intended for Death Wish to be directed by Sidney Lumet, with Jack Lemmon starring in the lead. Winner was characteristically waspish in his retort, saying “the novel sold three copies – to his mother. Nobody bought the novel. It was about a man who goes out and kills citizens. Brian Garfield said, ‘Oh, they made this terrible, bloodthirsty film!’ Well, what did he think he’d written? Snow White? The man’s a bloody idiot!”

Death Wish was so successful that it spawned a franchise. Bronson played Kersey five times in all (1974, 1982, 1985, 1987 and 1994), much to Garfield’s chagrin. “I hated the four sequels,” he said in 2008. “They were nothing more than vanity showcases for the very limited talents of Charles Bronson.” The films continued to arouse controversy, especially when, in 1984, Bernhard Goetz was dubbed the “subway vigilante” after shooting four young black men on a New York City train.

Asked for his reaction, Winner offered the incredibly insensitive quip, “I don’t approve of what Mr. Goetz did, but I have to say, if he has to shoot anyway on the subway, I wish he’d do it in the week we’re opening.” In 2015, Donald Trump invoked the demagogic spirit of Bronson’s character during a rally in Tennessee, when he boasted of owning a handgun permit, adding “somebody attacks me, they’re gonna be shot”. As fans chanted Bronson’s name, Trump told them that Death Wish would not be made today “because it’s not politically correct”.

When Esquire ran an article quoting Bronson as saying he was capable, like his character, of killing anyone who harmed his family, television host Johnny Carson asked him why a magazine published quotes like that. “Because that’s what I said,” Bronson replied. The actor was no stranger to controversial outbursts, declaring in 1972, the year his daughter Zuleika was born, that he would “leave America immediately if any of these things these Women’s Libbers want were to come about. Women are not equal – never could be,” he insisted.

Bronson had a fraught relationship with the press and said he hated being “probed” by reporters. When journalist Stephen Whitney, whose credits include ghostwriting It’s Your Body: A Woman's Guide to Gynaecology, penned a 1975 biography called Charles Bronson Superstar: The Real Man Behind the Rock-Hard Macho Image, the actor was livid. “There are very unflattering things in it about Jill. He tried to stop it, but he couldn’t. He threatened a whole lawsuit. He bought up, or tried to, every copy of it. You couldn’t get it after the first printing,” Harriett Bronson told wearemoviegeeks.com in 2011.

Bronson disliked film critics, too, saying: “We don’t make movies for critics, since they don’t pay to see them anyhow.” Roger Ebert interviewed him in 1974 and commented, “he really does seem to possess the capacity for violence. It is there in his eyes.” When they discussed critic Jay Cocks’s hostile review of The Stone Killer, Bronson added menacingly, “One way or another. Sooner or later, I’ll get that man. Not physically, but I’ll get him.”

Ireland was certainly aware of her husband’s temper, even joking about it when the pair appeared on the Dick Cavett Show in 1972. Bronson railed against Nicolas Gessner, the director of Someone Behind the Door, a French-produced film Bronson, Ireland and Anthony Perkins made in Folkestone the previous year. Bronson repeatedly mocked Gessner as “a thick Swiss director” [Gessner was actually Hungarian, born in Budapest], claiming that “he ruined the whole picture”. When Cavett asked what happened, Ireland said, “Oh, Charlie just grabbed him by the throat and gave him a good shake”.

Winner said he knew about Bronson’s “reputation for blowing up and hitting people on pictures”, and the actor made no secret of his problems with directors, saying that he found 60 per cent of them “difficult”, full of what he called “Hollywood bulls--t”. He went further in an interview with Paris Cine Revue reporter Lina Coletti in 1971, stating, “most producers are cretins, most directors are idiots. Everyone in film thinks only of money”.

He was also scathing about younger Hollywood stars, accusing them of being “full of bull”. “I can play the character better because of my experience – because of the things I’ve been through,” he told The Washington Post in 1977. “All those Method Guys – like that De Niro, Stallone and what’s his name, Pacino – they’re all the same. They even look the same.” He dismissed Academy Award nominations as “a lot of bunk”. Bronson’s only major nomination, for an Emmy, came in 1961, when he played Soldier Conlon in a General Electric Theatre television show called Memory in White, starring the future President Ronald Reagan.

Many of the directors who knew Bronson had amusing stories about their problematic relationships with the actor. According to A Siegel Film: The autobiography of Don Siegel, when he was directing Telefon, actress Lee Remick was petrified of playing a scene with Bronson in which she had to touch his face. When Siegel asked why, she replied, “I don’t dare. He’ll bite me!”

Bronson played a bare-fisted brawler in Walter Hill’s 1975 debut film Hard Times. The Depression-era movie also starred Ireland, one of the 11 films she made with her husband. In a conversation with The Hollywood Interview, Hill recalled working with Bronson. “He was in remarkable physical condition for a guy his age; I think he was about 52 at the time,” said Hill, who went on to direct Southern Comfort and 48 Hrs. “He had excellent coordination, and a splendid build. His one problem was that he was a smoker, so he didn’t have a lot of stamina. I mean, he probably could have kicked anybody’s ass on that movie, but he couldn’t fight much longer than 30 or 40 seconds. We had kind of a falling out over the film. He thought I’d been a little too… how do I put this? Too draconian in my editing of his wife’s scenes.”

Hill said he ran into Bronson several times afterwards. “One time at a party, he passed me and cut me dead; wouldn’t even say hello. A year after that, we ran into each other again, and it was like we were old friends. So he ran hot and cold,” added Hill.

Billy Crystal also experienced the cold treatment from Bronson. In 1991, he sent Bronson the script for City Slickers, in the hope of hiring him to play the old cowboy Curly. A day later, Bronson rang him. “He cursed me out,” the Emmy-winning comedian said, in June 2021. “Bronson said, ‘I’m dead on Page 53. How could you do this? Nobody kills Charles Bronson – didn’t you see my Death Wish movies? I don’t die!’”

When Crystal tried to explain that Curly’s death was the catalyst for the other characters to take charge of the cattle drive, “Bronson said, ‘f--k you, I’m dead’ and hung up.” An amusing postscript came at an after-party at the Cannes Film Festival, when Jack Palance was being feted for his role as Curly, a part that earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Crystal saw Bronson sitting on a couch with Sean Penn. “I just looked at him and nodded my head. He got up and walked out,” recalled Crystal.

Penn, who worked with Bronson on his directing debut with The Indian Runner, said he found the actor to be a man of “great dignity”, coping in the aftermath of wife Jill’s death at 54 from cancer. But Penn also found that Bronson did not want his character to die on screen. “Bronson asked me if it was necessary to have his character’s suicide, because he wasn’t so sure his Italian fans would be so happy seeing him do that,” Penn told Roger Ebert. The young director said he had got on well enough with Bronson to banter with him after joking that he hadn’t really needed to shave off his signature moustache. “You better not be kidding, you sonuvabitch,” said Bronson.

After one final creaking Death Wish outing in 1994 – playing an OAP vigilante at 72 – Bronson spent his remaining working years filming the made-for-television A Family of Cops trilogy before a hip replacement forced his retirement. By the time of the third instalment, when he was 77, Bronson had married 38-year-old actress Kim Michele Weeks. She starred as his love interest in Family of Cops III and was with Bronson until he died in Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre in Los Angeles at the age of 81.

Harriett Bronson later gave interviews accusing Weeks of all manner of connivances, including alleging that Weeks banned Bronson’s family from visiting the actor as he lay dying from respiratory failure, metastatic lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The public fall-out would have pained a man who prided himself on being “secretive, very private, like a hermit”.

According to his will, Bronson, who’d shrewdly negotiated large percentages and video rental revenues from his later films, was worth more than £60m in today’s money. Earnings from more than 100 films allowed the former impoverished miner from Pennsylvania to leave a 33-room Bel Air mountaintop mansion, a 260-acre farming estate in Vermont and a luxury house in Malibu. With so much money involved, there were the predictable accounts of recriminations over who-got-what.

The most touching thing Bronson left behind was his own oil painting of ‘Scooptown’, which was owned by Harriett. It was another example of how Bronson never really got over his past. Kurt Russell was 12 when he acted with Bronson on the 1965 western Guns of Diablo. When he heard it was Bronson’s birthday, the youngster bought the middle-aged star a remote-controlled aeroplane. “He just kinda looked at me and looked at the ground and walked away,” Russell told Jimmy Kimmel in 2018, describing Bronson’s reaction. A while later, a producer told Russell that Bronson wanted to see him in his trailer. “Nobody ever really got me a present before,” said Bronson, before quickly shutting the door.

Four months later, on the day Russell became a teenager, a smiling Bronson gave him a state-of-the-art skateboard. When Bronson found out that a security guard had banned Russell from using it on the MGM lot, he marched with Russell straight to the studio boss, telling him forcefully: “We’re both gonna be skateboarding around the lot.”

On or off screen, Charles Bronson was not a man to mess with.