On stage and when we met at the theatre, the Queen was a figure of quiet wisdom and humour

“I’ve never been fond of the theatre.” So says Q (an older Queen Elizabeth II) in Moira Buffini’s Handbagged. Two things strike me about that statement: we have no idea if it is true and, if it is, the sentiment is certainly not reciprocated. Looking back at theatre over the last four decades, it is fascinating to see how often the late Queen was portrayed on the British stage and how sympathetically she was seen in contrast to the passing parade of politicians.

In Shakespearean drama monarchy is often equated with solitude. Richard II is aware of the vanity of ceremony and achingly cries that a king “needs friends”. Henry IV is racked by guilt and even Henry V, on the eve of Agincourt, dwells on the tragic isolation of kingship.

And it’s not just in Shakespeare. Elizabeth I in Schiller’s Mary Stuart is haunted by the responsibility for the death of her cousin, and Philip II in Don Carlos ruminates on filial treachery. Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown: it is a constant theme of world drama.

Even in the age of constitutional monarchy, that strain recurs. What is more striking is the way Elizabeth II was often seen as a repository of quiet wisdom. The first dramatist to treat her seriously was Alan Bennett in A Question of Attribution at the National Theatre in 1988. In one scene the monarch (played by Prunella Scales) confronts Anthony Blunt, who was both surveyor of the Queen’s pictures and a Communist spy.

With canny skill, she steers Blunt on to the subject of artistic forgery and suggests that it may sometimes be better not to express doubts about a painting’s provenance: “Stick to the official attribution rather than let the cat out of the bag and say, ‘Here we have a fake.’” Which is exactly what the monarchy did with the perfidious Blunt.

The scene is obviously Bennett’s invention but the Queen’s public reticence gives the dramatist poetic licence. That ability to recreate Elizabeth II on one’s own terms was exploited to great effect by Sue Townsend in her bestselling book and subsequent 1994 play, The Queen and I. Townsend’s premise was that, in a new republic, the whole Royal family had been transplanted to a Leicester housing estate. The play was clearly an attack on a world of inherited privilege. Yet even here the Queen emerged, in Pam Ferris’s performance, as a likable figure liberated from a world of cosseted ritual and able to discover her hidden talents.

But where dramatists really scored was in contrasting Elizabeth II’s incremental political experience with the expedient needs of her prime ministers. Peter Morgan in The Audience in 2013 imagined the monarch’s weekly audience with eight of her prime ministers, from Churchill to Cameron. This may have been intelligent speculation but the head-to-head conflict between the Queen (Helen Mirren) and Margaret Thatcher (Haydn Gwynne) over the issue of South Africa (“Black South Africans want sanctions” urged the Queen) had the ring of truth. Exactly the same battle recurred in Handbagged, not only over South African sanctions but over Thatcher’s assertion that there is no such thing as society.

What does this prove? Simply that a constitutional monarchy – which Shaw once called “a bulwark against dictatorship” – gives the dramatist the freedom to exercise his or her imagination. But the portrait of Elizabeth II that has emerged, as a passionate defender of the Commonwealth, a shrewd operator and a figure of quiet humour, feels entirely plausible.

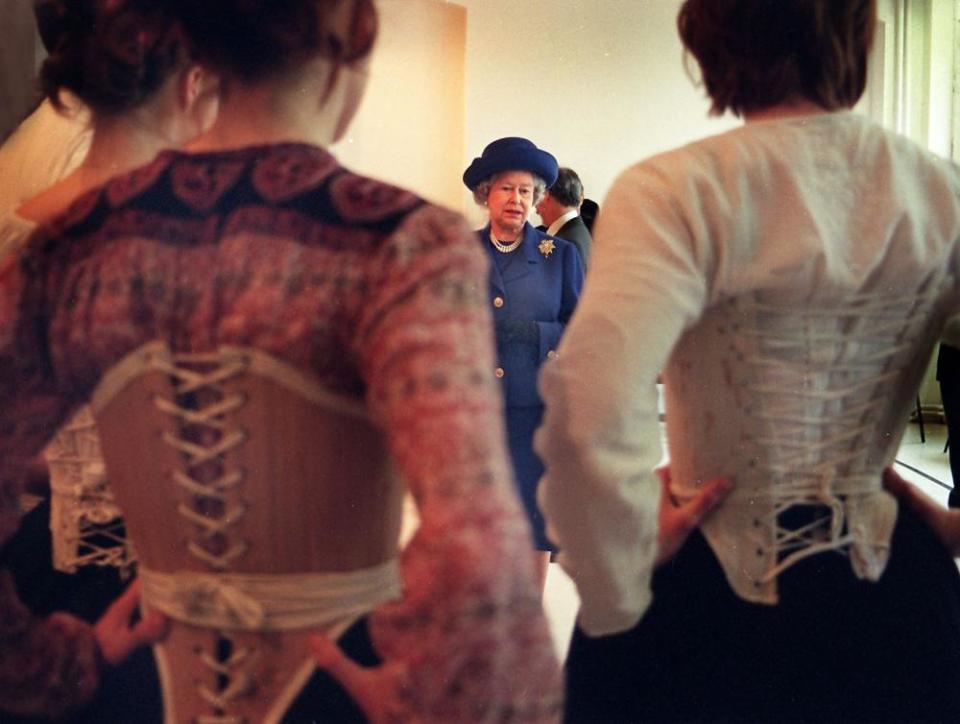

My one encounter with her took place when the National Theatre’s production of Oklahoma! transferred to the Lyceum theatre in 1999 and the critics were invited to meet her in the interval. It was the culmination of a 12-hour celebration of London theatre and one of my colleagues said to the Queen that he had been following her all day and was totally exhausted. “Every day,” she remarked, “is a bit like this. “You start off in Birmingham and you never know where you may end up.”

Forsaking etiquette, I even had the temerity to ask her if seeing Oklahoma! again brought back happy memories. Her eyes lit up as she said that it was the first show she and Philip had seen together when they got engaged. Whatever she says in Handbagged, on that day at least the Queen seemed extremely fond of theatre.

Handbagged is at the Kiln theatre, London, until 22 October.